Scene 1 (0s)

96 FOUNDATIONS Epidemiology Weakness, a common ED complaint, can reflect a vast array of pathol- ogy with varying degrees of severity. Patients may use to the term weakness to describe either focal or systemic complaints and often use the broader description of weakness to convey otherwise vague or sub- jective symptoms, such as fatigue, lethargy, or general malaise. As a result, weakness as chief or associated complaint can be quite challeng- ing, both from a diagnostic and therapeutic perspective. Up to 10% of ED visits are for generalized weakness, with a prepon- derance of the complaint among elders. Over half of these patients are identified as having a serious condition, and the diagnoses span cardio- vascular, hematologic, neurologic, toxicologic, psychiatric, endocrine, pulmonary, metabolic, and infectious causes.1 This chapter focuses on the initial evaluation of the generalized com- plaint of weakness and the specific evaluation of acute neuromuscular weakness. The latter may be focal or generalized and may originate in central or peripheral nerves, the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), or myofibers themselves. Other chapters in this text provide additional information regarding the diagnosis and management of specific neu- rologic causes of weakness including the brain and cranial nerves (CNs; see Chapter 91), spinal cord (see Chapter 92), and peripheral nerves (see Chapter 93), as well as neuromuscular disorders (see Chapter 94). Pathophysiology There are many diagnostic considerations for the patient presenting with diffuse weakness (Box 9.1). While a singular cause of weakness may be identified, elders and patients with multiple medical problems may have numerous factors contributing to weakness. Alterations in plasma volume, electrolyte imbalance, anemia, decreased cardiac function, drop in systemic vascular resistance, increased metabolic demand (infection, toxin, endocrinopathy), and mitochondrial dys- function (severe sepsis) can all produce non- localized weakness. A global depression in central nervous system (CNS) activity from sed- ative effects or stimulant withdrawal can also present as generalized weakness. Focal weakness confined to one area in the face or body (left, right, distal, or proximal) typically indicates a localized neurological issue corresponding to a specific area of the central or peripheral ner- vous systems (PNSs). Lesions involving the motor areas of the cerebral hemispheres may cause unilateral weakness, and lesions in the cerebral cortex outside the motor area may cause receptive or expressive aphasias and complex cerebral motor deficits such as apraxia. Peripherally, the spinal nerves extend from the anterior horn of the spinal cord and represent the ana- tomic origins of the lower motor neuron (LMN). The neuroanatomic distinction between LMNs and upper motor neurons (UMNs) is essen- tial in localizing lesions. DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH Differential Considerations The differential diagnosis for generalized weakness is broad. Consid- eration of systemic causes such as infectious, neurological, toxicologic, metabolic, and physiological causes is important (see Box 9.1). The first step is to address potential life threats, major systemic conditions, and disorders requiring emergent intervention. A detailed history should elucidate the nature, onset, and progression of symptoms, exacerbat- ing or alleviating factors, and fluctuations in severity that may help discern if weakness is a result of cardiovascular disease, pulmonary insufficiency, metabolic disturbance, concurrent infection, toxic inges- tion, medication imbalance, or malignancy. Medication reactions or interactions are an important consideration in patients taking multiple medications. A thorough review of systems should also be performed to identify associated signs or symptoms that may help to form a unify- ing diagnosis. For example, a review of systems might reveal orthopnea and symptoms of congestive heart failure in the fatigued patient with significant cardiac disease, chronic blood loss in the anemic patient, or incontinence in an older adult with a urinary tract infection. Elders often present with less localizing symptoms of infection, such as dysuria or frequency in the case of a possible urinary tract infection, and require a broad diagnostic approach, including laboratory and radiological studies. Vital sign abnormalities, including bradycardia, tachycardia, tachy- pnea, fever, hypothermia, or hypotension should prompt immediate intervention and a search for a systemic cause of the weakness. A Weakness Andrew J. Eyre 9 KEY CONCEPTS • Weakness is a common complaint among emergency department (ED) patients, with a preponderance in elders and those with chronic disease, and therefore may require a broad approach to investigating underlying causes. • Patients may use the term weakness to reflect a variety of vague symptoms including decreased motor strength, fatigue, poor energy, dyspnea, or even depression. • Global weakness is typically caused by a systemic condition while a focal neurologic deficit or pattern can often be traced to a specific lesion within the central or peripheral nervous systems. • Although not always detectable in the acute period, lesions to the upper motor neurons (UMNs) tend to produce signs that include spasticity to extension in the upper extremities, spasticity to flexion in the lower extrem- ities, hyperreflexia, pronator drift, and Hoffmann and Babinski signs. • Lesions to lower motor neurons (LMNs) typically result in flaccidity, decreased reflexes, fasciculations, or muscle cramps. Downloaded for mohammad talebi ([email protected]) at CK Global Selfmanra Test from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on July 25, 2025. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2025. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved..

Scene 2 (1m 5s)

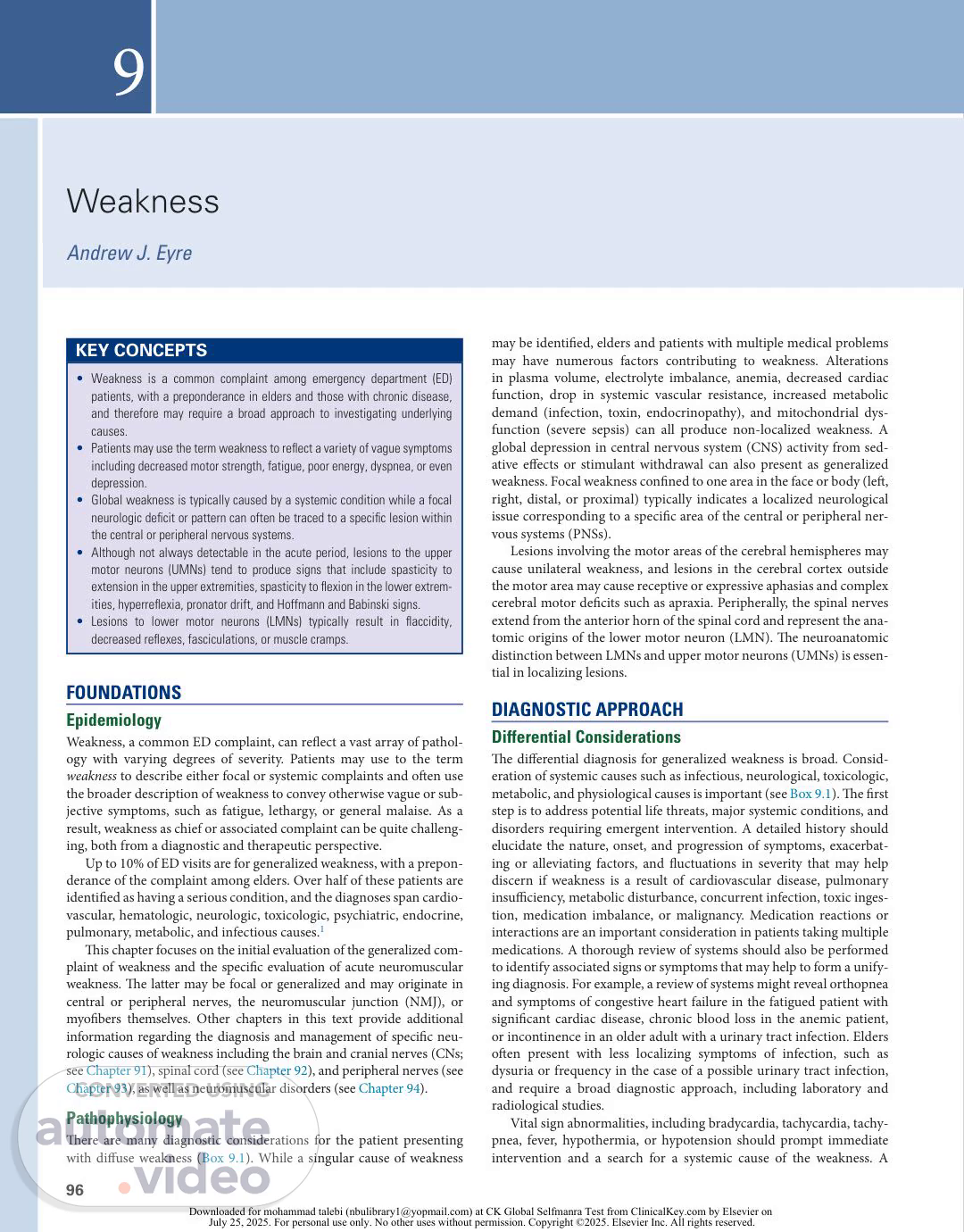

97 CHAPTER 9 Weakness general detailed physical examination, including evaluation of the skin and mucous membranes, may provide evidence of systemic disease. A cardiovascular examination can give the clinician a sense of the ade- quacy of circulation. A carefully performed neurologic examination is important to determine the occasionally subtle presentations of focal central or PNS lesions. If history, physical examination, and ancillary testing do not iden- tify a systemic cause of weakness, the investigation should broaden to include consideration of neural or primary muscular causes for weak- ness. Focal causes of weakness include central and peripheral neu- rological disease. Conditions involving UMNs tend to produce signs that include spasticity to extension in the upper extremities, spasticity to flexion in the lower extremities, hyperreflexia, pronator drift, and Hoffmann and Babinski signs. UMN signs signify a lesion within the cerebral cortex or corticospinal tract (CST) of the brainstem or spinal cord. Although these findings are not always detectable in the acute period, the presence of even one of them suggests pathology within the CNS. Weakness caused by LMN dysfunction is often accompanied by flaccidity, decreased reflexes, fasciculations, or muscle cramps. Lesions in the anterior horn of the spinal cord and its axonal extensions at the nerve root and peripheral nerve produce these findings. Diagnostic Algorithm Critical and Emergent Diagnoses Fig. 9.1 describes the approach to evaluating acute weakness. Gener- alized weakness can be explored by systematic consideration of the cardiac, neurological, metabolic, and infectious etiologies that can manifest as generalized weakness. This includes an evaluation of car- diac function, including consideration of acute reduction in cardiac output or worsening contractility leading to congestive heart failure.1,2 Further evaluation of circulation should include assessment of hemo- globin, oxygen saturation, and systemic vascular tone. Next, assess plasma volume and its composition to evaluate dehydration and altered nutrient (glucose), electrolyte (Na, K, Ca), or waste product (CO2, urea, bilirubin, ketoacid, ammonia, etc.) levels which can produce diffuse weakness. If substrate delivery and plasma composition appear suffi- cient, consider disturbances of cellular metabolic machinery second- ary to an endocrinopathy, toxin, or mitochondrial dysfunction in the setting of infection. In particular, consideration of infectious causes of generalized weakness should include bacterial, viral, and rickettsial infections that may not be evident from initial laboratory results. Neurologic examination focuses on identifying acute findings that could support CNS impairment, including acute cerebrovascular events. Although generalized weakness can present deceptively as a focal deficit, particularly in areas already weakened by prior neurologic insult, focal findings, such as lateralizing weakness, numbness, gait instability, or CN defects, should prompt a more detailed exploration of a potential neurologic cause. After evaluating the potential systemic causes of weakness, the practitioner should then address the specific causes of the focal loss of muscle power. This requires elucidating the pattern of a patient’s weakness from the cortical neuron down through the CNS, PNS, NMJ, and myofibers. Table 9.1 lists the most important critical and emergent causes of acute neuromuscular weakness. Common clinical patterns of weakness can be classified and assessed as discussed in the following sections. Specific Presentations of Neuromuscular Disorders Unilateral Weakness Combination of arm, hand, or leg with ipsilateral facial involve ment. Weakness involving the combination of arm, hand, or leg with ipsilateral facial involvement is generally caused by a lesion in the contralateral cerebral cortex or the CSTs coursing down the corona radiata and forming the internal capsule. Mild forms can be limited to a loss of dexterity and coordination with hand movements. Moderate loss of power is termed paresis, while complete loss of motion is termed plegia. UMN signs are useful corroborative findings but may not always be present, especially in the acute phase. Sensory disturbances commonly occur over the areas of weakness. Evaluate for associated neglect, visual field loss, or expressive or receptive aphasia to localize the problem to the cortex. Patients with equal loss of strength to the face, hand, and leg are more likely to have a subcortical lesion disrupting all these fibers as they funnel close together in the internal capsule. Concomitant head- ache is concerning for brain hemorrhage or mass lesion, although com- plex migraines can produce focal neurologic deficits.1 Sudden onset of this weakness pattern often suggests hemorrhage or acute ischemia, whereas a gradual onset may be seen in demyelination (e.g., multiple sclerosis, acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis) or neoplasm.1 Combination of arm, hand, or leg with contralateral facial involve ment. Weakness involving the combination of arm, hand, or leg with contralateral facial involvement indicates a brainstem lesion. A careful CN examination can provide more clues. If the patient has contralateral facial findings, there will likely be ptosis (CN III or sympathetic fibers) or a facial droop with forehead involvement (CN VII nucleus). Signs of CN V, VI, VIII, IX, or XII dysfunction will help localize to a particular level within the brainstem. Cerebellar findings or nystagmus may also be present on examination. Sensory disturbances can parallel the weakness, and some patients will report double vision, trouble swallowing, slurred speech, vertigo, or nausea and vomiting. The CST courses ventrally through the brainstem, and extremity weakness with UMN signs in the involved limbs may accompany brainstem lesions. Depressed consciousness can also occur if the brainstem reticular activating system is involved. The two main underlying processes that cause unilateral extremity weakness with contralateral facial involvement are vertebrobasilar insufficiency and demyelinating diseases. Combination of arm, hand, or leg without facial involvement. Weakness involving the combination of arm, hand, or leg without facial involvement is most likely to be a result of one of the following three processes: �•� �A�lesion�in�the�medial,�contralateral,�cerebral�homunculus�(over�the� area where the lower extremity is represented) �•� �A�discrete�internal�capsule�or�brainstem�lesion�involving�only�the� corticospinal rather than the corticobulbar tracts �•� �Brown-�Séquard�internal�capsule�or�brainstem�lesion�if�the�patient� also has contralateral hemibody pain and temperature sensory dis- turbances below the level of motor weakness. Importantly, however, before a patient is placed in this category, a careful examination of facial symmetry is required to determine that subtle facial droop or effacement of the nasolabial fold is not present. BOX 9.1 Nonneurologic Weakness Alterations in plasma volume (dehydration) Alterations in plasma composition (glucose, electrolytes) Derangement in circulating red blood cells (anemia or polycythemia) Decrease in cardiac pump function (myocardial ischemia) Decrease in systemic vascular resistance (vasodilatory shock from any cause) Increased metabolic demand (local or systemic infection, endocrinopathy, toxin) Mitochondrial dysfunction (severe sepsis or toxin- mediated) Global depression of the central nervous system (sedatives, stimulant with- drawal) Downloaded for mohammad talebi ([email protected]) at CK Global Selfmanra Test from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on July 25, 2025. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2025. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved..

Scene 3 (2m 10s)

98 PART I Fundamental Clinical Concepts Isolated extremity weakness (monoparesis or monoplegia). Isolated weakness of one extremity is usually caused by a spinal cord or peripheral nerve lesion. Examination for UMN signs in the affected limb will help uncover rare monomelic presentations of CNS lesions. If UMN signs such as hyperreflexia or spasticity are present, a careful evaluation is performed for facial weakness or involvement of the contralateral or other ipsilateral limb as indicative of a central process. If weakness is in the entirety of one lower limb, one should ensure that the patient does not have a contralateral pinprick level indicative of Brown-�Séquard�hemicord�syndrome.�Monomelic�weakness�is�often�the� result of a radiculopathy, plexopathy, peripheral neuropathy, or NMJ disorder. See Table 9.1 for emergent and critical PNS diagnoses. Lower extremities Cauda equina syndrome Upper extremities Central cord syndrome Guillain-Barré syndrome Chronic polyneuropathy Yes Yes Isolated CN VII Not Isolated to CN VII Brainstem lesion Neuromuscular junction disorder Cranial polyneuropathy Yes Yes Yes Yes Facial muscles only? No No No No Generalized weakness with no focal loss of muscle power Unilateral weakness: one limb only? Unilateral weakness: combination of arm, hand, or leg See list of non- neurologic weakness Proximal extremities only? Distal extremities only? Signs of radiculopathy, plexopathy, or neuropathy? Ipsilateral face involvement? Lesion of: cerebral cortex, corona radiata, or internal capsule No face involvement? Lesion of medial cerebral cortex, Consider: Myocardial ischemia if older or diabetic with upper extremity weakness and no measurable loss of power Consider: Discrete motor strip lesion Brown-Séquard hemicord syndrome (contralateral pain loss) Lower extremities Anterior cord syndrome Cauda equina syndrome All four extremities Cervical anterior cord syndrome Guillain-Barré syndrome Guillain-Barré syndrome Consider Myositis Rhabdomyolysis Neuromuscular junction disorder Mastoiditis Parotitis Idiopathic Upper extremities Central cord syndrome Neuromuscular junction (no sensory deficit) discrete CST lesion, or Brown-Séquard hemicord syndrome Contralateral face involvement ± other CN deficits? Lesion of brainstem Yes No No Bilateral weakness? Fig. 9.1 Common Clinical Patterns of Weakness, Classified and Assessed. CN, Cranial nerve. Downloaded for mohammad talebi ([email protected]) at CK Global Selfmanra Test from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on July 25, 2025. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2025. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved..

Scene 4 (3m 15s)

99 CHAPTER 9 Weakness The examination for monomelic weakness presentations includes detailed strength testing and determination of whether weakness local- izes to one ventral nerve root myotome or one particular peripheral nerve within the limb. Reflexes with a peripheral nerve disorder will be diminished, not hyperactive. Although radiculopathies can occa- sionally be purely motor, most peripheral lesions have some sensory component to their presentation; therefore, a careful sensory examina- tion in the distribution of dorsal nerve root dermatomes and periph- eral nerves is essential. See Box 9.2 for a list of nonemergent causes of peripheral neuropathy. NMJ disorders are considered when suspicion is low for a UMN source of isolated extremity weakness, reflexes are intact, and there are no sensory deficits to suggest a nerve or root problem. In such cases, the weakness is often mild, fluctuating, and worse later in the day. It usually involves the proximal arm or leg muscles, wrist extensors, fin- ger extensors, or ankle dorsiflexors. NMJ disorder–induced weakness with only monomelic symptoms will be an uncommon diagnosis in the ED. Bilateral Weakness Lower extremities only (paraparesis or paraplegia). When weakness involves the lower extremities only, the first consideration is a spinal cord lesion. If this is the case, UMN signs may be absent in the acute period. Because the lateral spinothalamic tracts (LSTs) run in proximity to the CST, patients with bilateral lower extremity weakness frequently have alterations to their perception of pain or temperature. Examination may reveal a loss of pinprick sensation to a particular spinal level within the thoracic cord or terminal first lumbar segment. The lesion may be as high as T2 without producing upper extremity findings. The main causes of anterior cord syndrome are external compres- sion, ischemia, or demyelination. In the absence of UMN signs or a clear thoracic pinprick level, evaluation of perianal sensation, rectal tone, and urinary retention can identify deficits that point to cauda equina syndrome, compression of peripheral nerve roots running below the termination of the spinal cord. If the physical examination does not support a cord syndrome or cauda equina compression, the patient may have a peripheral neuropathy affecting the longest nerve tracts first. The acute presentation that is most concerning is Guillain- Barré�syndrome�(GBS).�Rapid�demyelination�of�peripheral�nerves�can� result in symmetric weakness ascending from the feet. Sensory find- ings parallel the weakness, and reflexes should be decreased at some point in the patient’s clinical course. (1) Upper extremities only. When weakness involves the upper extremities only, the lesion is localized within the central portion of the cervical spinal cord where corticospinal fibers designated for hand and arm strength are located. The patient may have pinprick sensory loss over the upper extremities from the involvement of crossing sensory axons destined for the contralateral LST. However, light touch sensation, mediated by the posterior columns, should remain intact. Common causes of central cord syndrome include cervical spine hyperextension injuries and syringomyelia. All four extremities without facial involvement (quadriparesis or quadriplegia). When weakness involves all four extremities without facial involvement, the primary concern is a cervical spinal cord injury or process, but the patient is first assessed for medical conditions that produce global weakness. The more dense the extremity weakness, the more likely it is that the patient has a cervical spinal cord problem. Although all four extremities will test poorly for muscle strength, there is frequently some discrepancy between the lower and upper limbs in quadriparesis. Determination of sensory dermatomes by pinprick testing in the arms and hands, along with strength testing of specific myotomes, will allow localization of the level within the cervical spinal cord. One physical examination confounder in disorders that cause cord com- pression or ischemia is that upper extremity myotomes corresponding to the site of spine involvement will actually have LMN signs of flaccid weakness and decreased reflexes because anterior cells are involved at this particular level. However, UMN signs may be elicited below that level. A C5 lesion, for example, can cause diminished biceps reflexes but exaggerated triceps and patellar reflexes. Bilateral extremity weak- ness may occur in patients with GBS that has ascended from the lower extremity peripheral nerve myelin sheaths to the upper extremities. In this case, the lower limbs are usually weaker than the upper limbs. Proximal portions of extremities only. Weakness confined to the proximal portions of the upper extremities only points to a myofiber disorder, provided that there are no UMN signs or sensory deficits. Patients may report general fatigue or trouble raising the arms above the head, climbing stairs, or rising from a chair. The common acute and progressive causes of proximal muscular weakness are inflammatory diseases such as polymyositis or dermatomyositis, or necrosis, as in rhabdomyolysis from 3- hydroxy-3- methylglutaryl- coenzyme A TABLE 9.1 Critical and Emergent Causes of Neuromuscular Weakness Diagnosis Features Critical Diagnoses Cerebral cortex or subcortical Ischemic or hemorrhagic cerebrovas- cular accident (CVA) Brainstem Ischemic or hemorrhagic CVA Spinal cord Ischemia, compression (disk, abscess, or hematoma) Peripheral nerve Acute demyelination (Guillain- Barré syndrome) Neuromuscular junction Myasthenic or cholinergic crisis Botulism Tick paralysis Organophosphate poisoning Muscle Rhabdomyolysis Emergent Diagnoses Cerebral cortex or subcortical Tumor, abscess, demyelination Brainstem Demyelination Spinal cord Demyelination (transverse myelitis) Compression (disk, spondylosis) Peripheral nerve Compressive plexopathy (hematoma, aneurysm) Paraneoplastic vasculitis uremia Muscle Inflammatory myositis BOX 9.2 Nonemergent Causes of Peripheral Neuropathy Connective tissue disorder External compression (entrapment syndrome, compressive plexopathy) Endocrinopathy (diabetes) Paraneoplastic syndromes Toxins (alcohol) Trauma Vitamin deficiency Downloaded for mohammad talebi ([email protected]) at CK Global Selfmanra Test from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on July 25, 2025. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2025. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved..

Scene 5 (4m 20s)

100 PART I Fundamental Clinical Concepts (HMG- CoA) reductase inhibitors. Muscles are commonly but not always tender to palpation. Myositis patients can also have dysarthria and dysphagia from weakness of the pharyngeal muscles. Airway protective mechanisms may eventually be compromised. Chronic or recurrent myofiber pathology includes abnormalities to anchoring proteins supporting fibrils to the cytoskeleton and cell mem- brane (e.g., muscular dystrophies), dysfunctional ion channels respon- sible for depolarization of the muscle fiber cell (channelopathies such as hyperkalemic and hypokalemic periodic paralysis), or impaired ability to use carbohydrate and lipid energy sources (e.g., metabolic myopathies, mitochondrial myopathies). The presentation of these varied conditions ranges from insidious and progressive to sudden onset and episodic. Occasionally, a patient with an NMJ disorder will demonstrate proximal extremity or neck muscle weakness mimicking myofiber disease. Distal portions of extremities only. Weakness involving the distal portions of the extremities only is almost always caused by a peripheral neuropathy (see Box 9.2). Patients will have weakness and poor coordination with fine movements of their feet or hands. If this type of distal weakness is present in both lower extremities only, the patient will most likely have a chronic peripheral neuropathy or an acute demyelinating neuropathy (GBS). The patient will also have some sensory disturbance over the feet. Examination for perianal sensory deficits or issues with fecal or urine continence will help exclude the compressive polyradiculopathy of cauda equina syndrome as a cause of bilateral distal lower extremity weakness. If only the fingers and hands are involved, evaluation for central cord syndrome is performed. Bilateral lower cervical radiculopathies or symmetrical polyneuropathies are possible but much less likely. Facial Weakness Without Extremity Involvement Isolated facial weakness will appear in one of two forms. Unilateral facial droop. Isolated, unilateral weakness of the upper and lower halves of the face is caused by a CN VII problem. Causes for an isolated CN VII neuropathy are Bell palsy, mastoiditis, and parotitis. The examination must confirm that there is no extremity involvement and that other CNs, cerebellar testing results, and visual fields are normal. This will ensure that a brainstem lesion is not causing the weakness. Facial weakness not limited to cranial nerve VII. Facial weakness not limited to CN VII will be associated with some combination of ptosis, binocular diplopia, dysarthria, or dysphagia. It can be caused by a brainstem lesion, multiple cranial neuropathies, or NMJ problem. If there are no cerebellar findings, visual field deficits, sensory disturbances, or extremity UMN signs, posterior cerebral circulation and brainstem disorders are less likely, and an NMJ disorder is more likely. Dysfunction of one or more ocular, facial, or pharyngeal muscles will be the most common presentation for NMJ pathology. The history may indicate that the facial weakness is acute and progressive (botulism) or chronic and fluctuating (myasthenia gravis). Signs of these diseases can be determined by examining extraocular motion, facial expression, and soft palate rise. Generalized fatigue is often reported, and neck, extremity, and respiratory muscle weakness caused by involvement of these neuromuscular units may be present on examination. Patients with an abnormality of the presynaptic release of acetylcho- line (e.g., botulism, Eaton- Lambert syndrome, organophosphate poi- soning) can have autonomic ganglia involvement and hence abnormal pupillary response to light, dry mouth, fluctuations in heart rate and blood pressure, anhidrosis, or gastrointestinal and bladder dysmotility. Facial weakness from cranial polyneuropathy manifests with more than one CN deficit not localizing to a brainstem level and without any other long tract signs. These patients may have a variant of GBS or irri- tation of multiple CNs after they have exited the brainstem and pierced through inflamed meninges or malignant skull base metastases. EMPIRIC MANAGEMENT The management of neuromuscular weakness is based on evaluating the underlying cause and managing the acute complications of weak- ness. Airway protection in obtunded patients or those with upper airway compromise is paramount. Neck and pharyngeal muscle weak- ness, for example, may herald a risk for aspiration or airway obstruc- tion. Diaphragmatic weakness and inadequate hypopharyngeal muscle control or respiratory muscle fatigue should prompt definitive airway protection by endotracheal intubation. During rapid sequence intu- bation (RSI), succinylcholine should be avoided in suspected cases of progressive denervation of muscle of more than a 3- day duration due to receptor upregulation and the risk for severe hyperkalemia. In this situation, we recommend rocuronium, a nondepolarizing neuromus- cular blocking agent. New quadriparesis or quadriplegia and hypotension without another cause is assumed to be caused by failure of autonomic sym- pathetic fibers in the cervical spinal cord. Consider a volume load and pressor support in addition to emergent imaging of this area. Although new weakness localizing to the spinal cord calls for immediate imag- ing, weakness from the spinal roots down does not always necessitate imaging in the ED unless cauda equina syndrome or other acute, emer- gent pathology is suspected. Patients with suspected GBS need pulmonary function testing in addition to admission to a critical care setting for further management. An infectious or metabolic trigger is sought in patients with myas- thenic crisis. If the patient is currently on acetylcholinesterase inhib- itors, consideration should be given to a cholinergic crisis. Be aware of medications that may worsen weakness in patients with NMJ disease (e.g., aminoglycosides, quinolones, beta blockers). Rhabdomyolysis is treated with aggressive fluid resuscitation and intervention directed at the primary cause, if known. In any patient with a sudden onset of focal weakness, a vascular cause (occlusion or hemorrhage) should be strongly considered until excluded by an adequate imaging study. The presence of a severe head- ache with unilateral weakness, or midline back pain with lower extrem- ity weakness, alerts the clinician to a compressive space- occupying lesion of the CNS or spinal cord, respectively. Patients with UMN signs have weakness that localizes to the spinal cord CST or above and are considered to have an emergent problem. They may be at risk for progression to sympathetic autonomic failure or obtundation from enlarging space- occupying spinal or cerebral lesions, respectively. The presence of anorectal or bladder insufficiency without another explanation suggests a UMN or cauda equina lesion. Laboratory tests are most useful for excluding non- neuromuscular causes of weakness (electrocardiography, measurement of hemoglo- bin, glucose, electrolytes, troponin, and lactate levels, urinalysis). Two exceptions are the creatinine kinase level in inflammatory myositis and potassium level in channelopathies. DISPOSITION Patients with generalized weakness should receive treatment and disposition based on the underlying diagnosis and anticipated clini- cal course, and the range of dispositions will vary based on etiology. Patients with identified central vascular lesions, thrombotic or hem- orrhagic, should be aggressively managed in the inpatient setting. Patients with mild LMN or myofiber weakness of benign origin may Downloaded for mohammad talebi ([email protected]) at CK Global Selfmanra Test from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on July 25, 2025. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2025. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved..

Scene 6 (5m 25s)

101 CHAPTER 9 Weakness be discharged with close follow- up, provided that the condition is not thought to be progressing rapidly. Those with more severe or progres- sive LMN or myofiber weakness and any patient with new UMN weak- ness should be admitted for further testing. Patients with suspicion for ascending paralysis should be admitted to an ICU setting for close respiratory observation. The references for this chapter can be found online at ExpertConsult. com. Downloaded for mohammad talebi ([email protected]) at CK Global Selfmanra Test from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on July 25, 2025. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2025. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved..

Scene 7 (5m 55s)

101.e1 REFERENCES 1. Long B, Koyfman A. Clinical mimics: an emergency medicine- focused review of stroke mimics. J Emerg Med. 2017;52(2):176–183. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.09.021. 2. Larson S, Wilbur J. Muscle weakness in adults: evaluation and differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(2):95–108. C H A P T E R 9 : Q U E S T I O N S A N D A N S W E R S 1. A 65- year- old man with a history of atrial fibrillation, on warfarin, with a supratherapeutic international normalized ratio (INR) of 4, presents with sudden onset right leg weakness and back pain. On examination, he is tachycardic to 108 beats/min and has 3/5 weak- ness to the right hip flexors and extensors, knee flexors and exten- sors, as well as ankle dorsiflexion and great toe extension. However, ankle plantar flexion is preserved. His knee reflexes are absent, but Achilles reflexes are normal. He has a normal Babinski reflex and no spasticity. He has sensory deficits throughout the anterior and posterior parts of his proximal leg as well as the anterior lower leg and dorsum of the foot. His posterior lower leg and plantar surface, however, have normal sensation. Rectal tone is normal, and there is no urinary retention. What is the most likely diagnosis? a. Anterior cord syndrome from epidural hematoma b. Cauda equina syndrome c.� �Guillain-�Barré�syndrome d. Hemorrhagic anterior cerebral artery (ACA) distribution stroke e. Retroperitoneal hematoma with lumbar plexopathy Answer: e. This patient has a spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma compressing the lumbar nerve plexus. 2. A 45- year- old man has had gradual onset of progressive weakness to his face and trouble swallowing for 2 days. On examination, he has bilateral ptosis with dilated, poorly reactive pupils, bilateral upper and lower facial muscle weakness, poor soft palate rise, and slurred speech. His oral mucosa is dry. Arms and legs have 5/5 strength. He has no sensory deficits. He has a palpable distended bladder. His symptoms have not abated since onset, and they are getting worse. What is the most likely diagnosis? a. Brainstem stroke b. Botulism c. Muscular dystrophy d. Myasthenia gravis e. Organophosphate poisoning Answer: b. This patient has acute onset of progressive neuromuscu- lar junction weakness. He has autonomic findings of abnormal pupil response to light, dry oral mucosa from decreased salivary produc- tion, and a distended bladder. These imply that his problem is with the release of acetylcholine (ACh) rather than the nicotinic receptor. The latter would not have autonomic findings. The most appropriate cause of acute onset, progressive impairment in the release of ACh, as listed in the choices, is botulism. 3. A 23- year- old woman presents with the sudden onset of weakness of her face, arm, and leg 2 hours ago. On examination, she has weakness to her upper and lower face on the left. She cannot abduct her left eye. She has 3/5 strength to her upper and lower extremities on her right side. She has a right pronator drift and an upgoing toe on the right. Sensation is decreased in her right upper and lower extremities as well. There is no aphasia, neglect, or visual field defi- cit. What is the most likely diagnosis? a. Midbrain stroke because of cardioembolic stroke b. Middle cerebral artery (MCA) distribution stroke c. Multiple sclerosis d. Myasthenia gravis e. Pons stroke because of vertebral dissection Answer: e. This patient has acute onset of crossed face and extrem- ity weakness, with upper motor neuron (UMN) signs in the extrem- ities. Both upper and lower extremities are affected, which makes a corticospinal tract (CST) lesion more likely than a cerebral cortex lesion. Her left- sided facial weakness is representative of a periph- eral cranial nerve (CN) VII that is actually due to infarction of the CN VII nucleus in the brainstem. The CN VI deficit on that side is due to proximity of this nucleus as well. The CST runs just anterior to these nuclei within the brainstem. These CN nuclei lie in the pons. 4. A 21- year- old man awoke this morning with weakness to his right hand and right foot. He admits to drinking heavily the night before and falling asleep on the floor. On examination, he appears well, with weakness to right wrist extension and thumb extension, as well as sensory deficits over the dorsal surface of his hand and first and third digits. He also has weakness to ankle dorsiflexion and great toe extension on the right. He has sensory deficits over the anterior lower leg and the dorsum of his foot. Biceps and ankle reflexes are intact, he has no pronator drift, and his toes are downgoing. What is the most likely diagnosis? a. Brainstem stroke b.� �Brown-�Séquard�syndrome c. Compressive neuropathy d. MCA distribution stroke e. Polyradiculopathy secondary to disk disease Answer: c. He has radial nerve and peroneal nerve palsies because of compression while lying passed out on the floor for an unspecified time. 5. A 70- year- old man has had trouble swallowing and progressive weakness of his hands over the past 2 months. On examination, his speech is slurred, his voice is nasal, and he has fasciculations to his face, tongue, and over his pectoralis muscles and deltoids bilater- ally. He has 4/5 strength to shoulders, biceps, triceps, and hand grip bilaterally. Stiffness to extension is present at both elbows. He has bilateral pronator drift and 3+ biceps reflexes. He tends to smile inappropriately. He has no sensory symptoms. What is the most likely diagnosis? a. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) b. Brainstem stroke c. Chronic demyelinating polyneuropathy d. Parkinsonism e. Polymyositis Answer: a. This patient has lower motor neuron (LMN) signs (fascicu- lations) and UMN signs (pronator drift and increased reflexes) in sim- ilar distribution. The combination of upper and lower motor neuron involvement makes ALS the leading diagnosis among those listed. His dysphagia and inappropriate smiling are due to a release of the medulla from upper motor neuron regulation. Downloaded for mohammad talebi ([email protected]) at CK Global Selfmanra Test from ClinicalKey.com by Elsevier on July 25, 2025. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright ©2025. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved..