W1 Private equity demystified ch4 Doing a deal

Scene 1 (0s)

[Audio] Private Equity Demystified: An explanatory guide. Fourth Edition. John Gilligan and Mike Wright, Oxford University Press (2020). © John Gilligan & Mike Wright. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198866961.003.0004 4 Doing A Deal The Process of a Private Equity Transaction In this chapter we turn our attention away from the funds and look in more detail at the participants in a private equity deal. We walk through the array of advisers in the private equity universe, then examine the auction process that lies at the heart of many PE deals. In a new section, we look at the key terms that will be in most PE deals and consider why they are there and what they are seeking to control or incentivise. In Chapter 5 we turn to financial structuring and financial engineering. Who's Who in a Private Equity Transaction There are two sides to every corporate transaction: those acting with or for the purchaser (the buy side) and those acting with or for the owners of the target company, the shareholders (the sell side) (Figure 4.1). In a buyout the key parties on the purchaser's side are the private equity fund that will invest in the transaction, the bankers or other lenders who will lend in support of the deal, and their respective advisers. They must negotiate between them a funding package to support the bid. The bid will be made by a newly formed company, 'Newco', which will be funded by the bank and the private equity fund. The debt will be lent to a subsidiary of Newco, often called 'Debtco' or 'Midco', for reasons to do with the security of the loans that we will cover in Chapter 5. On the target's side are the shareholders, who are generally seeking to maximize the value they receive from any sale. They will be represented by the management of the business or by independent advisers (or both) who will negotiate with the private equity fund acting on behalf of Newco. If the target has a pension fund, the trustees of the fund may also negotiate with the private equity fund regarding future funding of the existing and future pension fund liabilities. The role of the incumbent management of the business in any buyout varies. They may be part of the group seeking to purchase the business and therefore be aligned with the private equity fund (as illustrated in Figure 4.1). This is often termed an insider buyout, or more often simply a management buyout or MBO. Pure MBOs are increasingly rare as vendors have taken control of the sale process as we describe later in this chapter. The private equity fund may be seeking to introduce new management if they successfully acquire the business. This is an outsider buyout, or management buy-in or MBI. In some circumstances management find themselves acting as both vendor and purchaser. For example, in a buyout by a private equity fund of a company that is already owned by another.

Scene 2 (3m 22s)

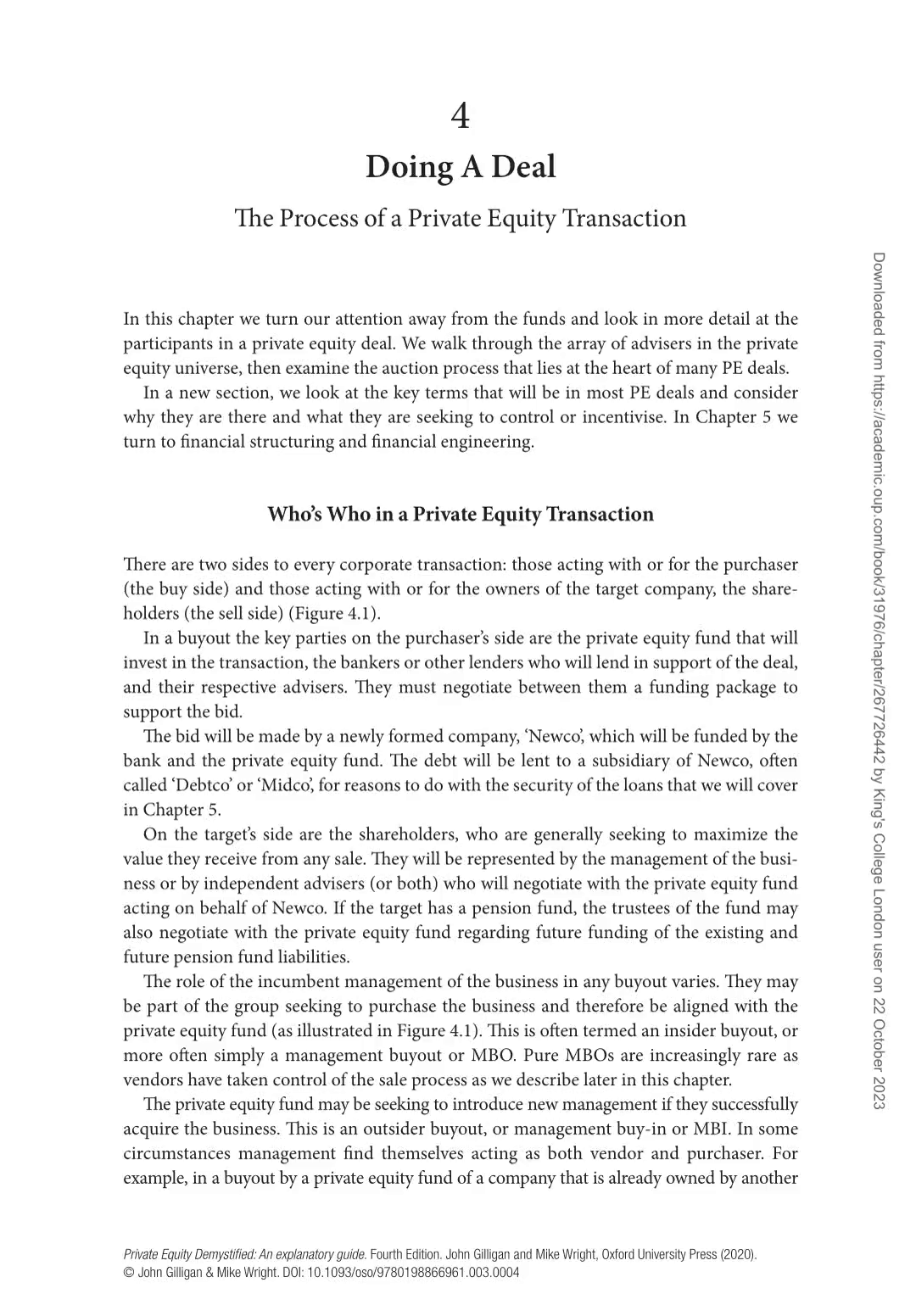

[Audio] 136 Private Equity Demystified PE fund, a so-called secondary buyout, management may on the one hand be vendors of their current shares but also be purchasers of shares in the company set up to acquire the target. We look at the mechanics of rolling over investments like this in Chapter 5. Where management have a conflict of interest, the shareholders' interests are typically represented by independent financial advisers and, in a quoted company buyout, by the independent non-executive directors of the target. The role and rewards of management are a key difference between a corporate takeover and a management buyout. In a management buyout, management will be expected to invest their own money in the business acquiring the target and expect to have the risks and rewards of a shareholder, not an employee, of that business. Most of the rewards to management therefore take the form of capital gains payable on successful exit, not salary and bonuses paid during the life of the investment. This tightly aligns the interests of management and investors. What Are the Roles of the Target's Wider Stakeholders? In general, the wider stakeholders have certain statutory protections against asset stripping and similar practices, but have only commercial influence at the time of, and subsequent to, any transaction. In Figure 4.1 there are no negotiations highlighted between the wider stakeholders and the acquiring or vending groups. In reality their position varies from deal to deal. If the assets of the target are being sold there are various rights created under TUPE legislation as discussed below. These rights were the source of much discussion in the UK and even led to a brief attempt to change legislation around employment rights. For this reason, we take a short detour to discuss TUPE. In summary TUPE rights are not additional to any rights under employment law, they protect them. Readers who do not care for such details can skip forward without any loss of continuity. PE Fund NEWCO Vendor DEBTCO TARGET TARGET Suppliers Customers Employees Pension Fund Trustes BUY SIDE Sell Side Equity % Bank/ Fund Suppliers Employees Customers Mgmt $/£ Share investment $/£ loan investment Equity% $/£ loan investment 100% 100% $/£ loan $/£ Share investment $/£ Consideration Paid Sales of Shares / Assets 100 % Figure 4.1. Participants in a leveraged buyout.

Scene 3 (6m 7s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 137 What Is TUPE and When Is It Applied? TUPE legislation is designed to protect UK (and EU) employees from being adversely impacted by the sale of businesses' assets rather than a sale of the shares in a company. TUPE was established in 1981, revised in 2006 to incorporate the EU Directive on Acquired Employment Rights and amended by the Collective Redundancies and Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) (Amendment) Regulations 2014. Employees have a legal contractual relationship with the company that employs them. This is embodied in their employment contract and is supplemented by protections guaranteed by employment law. When shares are sold and the ownership of the company transfers to new owners, this has no impact on the contractual relationship between the employee and the company being sold: the legal relationship remains unchanged and is legally identical before and after a sale. If a purchaser subsequently wishes to change any employment conditions it must do so in exactly the same way as if no sale had occurred. If the assets or the business undertaking are sold, rather than shares, the employees will have a new contractual relationship with the acquiring company. They will cease to be employed by their former employer and become employees of the company that bought the assets or undertaking. TUPE is designed to protect employees from employers who seek to use the change of legal employer to vary the employment terms or to use the sale to dismiss workers. TUPE gives employees an automatic right to be employed on the same terms (with the exception of certain specific occupational pension rights which are outside the scope of this report) by the new employer. These rights include the right to be represented by a trade union where the employees transferred remain distinct from the employees of the acquiring company. This is almost always the case in a primary private equity transaction because Newco has no business prior to the transaction, and therefore has no employees other than those acquired as part of the transaction. The regulations apply to all companies and public bodies without exception. The regulations require that representatives of the affected employees be consulted about the transfer by the employers. They have a right to know: that the transfer is to take place, when and why; the implications for the employees legally, socially, and economically; and whether the new employer intends taking any action that will have a legal, social, or economic impact on the employees. TUPE also places obligations on the selling employer to inform the acquirer about various employment matters. Advisers and Other Service Providers to Private Equity As we have stated, private equity funds outsource many functions. We discussed the in-house adviser in Chapter 2. Here we are focused on the advisory relationships at three stages of an asset's ownership cycle: acquisition of the target company, during the ownership life, and finally at disposal (Figure 4.2). We focus both on what the advisers are doing.

Scene 4 (9m 31s)

[Audio] 138 Private Equity Demystified and at the incentives that this creates in the broader private equity market, particularly in regard to reciprocity. Who Are Transactions Advisers? Private equity funds are transactional businesses that are always involved in, or preparing for, deals of one sort or another. This makes them prolific users of the advisory services that surround transactions. Transaction advisers generally include investment bankers, accountants and lawyers, and an array of consultants and experts working on the target company and its markets. Investment Bankers/Corporate Finance Advisers As we describe in the section on the M&A auction process below, the M&A teams of banks and other advisers run most M&A processes. This makes them both a source of deals for the private equity fund, when the investment bank is advising the vendor of a business, and a provider of advisory and distribution services (syndication) when advising the private equity funds. Thus, an investment bank may be providing advisory services to the newco and private equity fund at the same time as underwriting the banking and arranging the syndication of the transaction debt (Figure 4.3). This creates a complex series of incentives: the cor porate finance and syndication fees are, on the whole, payable only if a transaction completes. However, if a transaction that is not attractive to the market is arranged, the underwriting arm of the bank will be left holding the majority of the transaction debt. The incentives are therefore to maximize the transaction flow subject to the limitation of the appetite of the syndication market for debt. The bubble of the late 2000s in the secondary banking market released the normal action of this constraint and allowed the almost unrestrained growth in the size and scale of buyouts prior to the credit crunch. Furthermore the significant fees for advising and arranging the subsequent sale or flotation of the business will depend to some degree on the reputation for quality that an organization or individual builds up. Further complications arise around the notion of reciprocity. Private equity funds are a valuable source of a regular flow of sales and refinancing mandates that drive M&A fees. Typical Fund Advisers Placement Agents Legal Accounting Fund management & Reporting + Other Specialists Typical Acquisition Advisers Corporate Finance Legal Legal Accounting Acquisitions Disposals Investment Management PE Fund Accounting Strategy Operations HR Market Environmental IT Pensions Insurance HR/Management + Other Specialists + Other Specialists Typical Advisers at Disposal Typical Advisers During Ownership Corporate Finance Legal Accounting Market + Other Specialists Figure 4.2. Advisers and other service providers to private equity.

Scene 5 (12m 56s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 139 They are also potential buyers of many of the businesses that the advisers are retained to sell by other clients. As the scarcest thing in private equity is a good deal opportunity, there are powerful incentives to use reciprocity to try and ensure that the PE fund gets to 'see' every opportunity in their field of interest. Most advisers and funds activity measure and monitor reciprocity—i.e. who introduced what to whom. One increasingly common way to feed the reciprocity loop is to use buy-side advisers paid on a no-deal, no-fee basis. Given that the market developed for many years without these buy-side advisory relationships, it is natural to ask why they have emerged in the market. Whilst they fit with the outsourced model of private equity firms, there is also a suspicion that they are disguised reciprocity payments to advisers who may bring future deals. The vendor's advisers' role is described more fully in the later section on transaction process. Accountants Accountants provide due diligence and taxation advice on transactions and ongoing audit and tax advice to acquired companies. The corporate finance advisory businesses of the accountants also provide similar advisory services to those of the investment banks in the mid-market in many countries, but less so in the US. The accountancy firms (and other M&A boutiques) argue that they provide advice independent of the debt and equity distribution capacity that is provided by the investment banks. However, the accountancy firms sometimes provide both advisory and due diligence services to the same transaction. Where this is the case the relative size and contingency of the fees for these services needs to be considered to avoid a conflict of interest. Many private equity funds have sought to maximize the incentive of their due diligence advisers to be objective by forging long-term relationships with one or two providers. In these arrangements it is argued that the volume of transactions that any active private equity fund pursues will compensate the due diligence providers for the losses associated with those that do not complete successfully. Private equity fund Newco Target Co. Corporate finance Corporate finance Accountants Accountants Lawyers Lawyers Actuaries Actuaries Insurance Insurance Environmental Environmental Property Property Market Market Taxation Taxation Others Others Lead banker Syndicate debt providers Figure 4.3. Illustrative advisers to a typical transaction Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 6 (15m 42s)

[Audio] 140 Private Equity Demystified Lawyers Lawyers are providers of legal and tax advice on transactions, fund-raising and structures. Every party to each contract in a transaction will generally have a legal adviser. The legal contract is the deal. If there is any dispute about what was agreed, the signed contracts will be used to resolve or frame any disagreement. Lawyers provide both due diligence services, reviewing data on the target, and ne go tiation and documentation services in the production of the final legal agreements. The vendor's lawyers will often be responsible for managing the online dataroom that houses much of the company data provided to the purchaser. Commercial Due Diligence Most transactions will have some form of market due diligence provided by a sector expert from a third-party consultancy. In the early days of private equity many of these were small independent boutiques focused on specialist niches servicing businesses already in those sectors. Larger deals would attract the global consulting businesses, but private equity was not a core sector for most global consultancies. Today many of the niche practices have been acquired and consolidated by larger firms and PE is a major sector for all global consultancies. Reciprocity and Conflicts of Interest The volume and value of all private equity M&A transactions which we described in Chapter 1 amply explains the market opportunity for transactional advisers. Private equity is a consistent and predictable source of transactions, and transactions are the source of opportunities to all advisers and consultants. The reciprocity loop is common to many businesses where buyers and sellers can be either side of a transaction or relationship from time to time. However, one of the defining features of private equity has been the sharp incentives created by a desire by PE funds to have contingent success fee arrangements for their advisers. For PE funds this means that fees are largely only incurred when deals are completed. The advisers charge a premium to reflect their risks when faced with contingent fee arrangements. At completion those fees are charged to the acquiring company in a new deal or to the fund's investors in an exit. Contingent fees therefore reduce abort costs on deals that do not go ahead, but increase the costs to deals that do complete. As a result, deal fees reported in private equity transactions tend to be high, but the data does not reflect the abort costs that advisers incurred on deals that did not happen. This can create conflicts of interest between earlier and later funds. The fact that fees are generally charged to portfolio companies or to the fund's investors potentially creates perverse incentives. The principal–agent hypothesis says that the CEO of a quoted company may spend shareholders' money in the pursuit of schemes that do not maximize shareholder value. The PE fund manager may similarly use the ability to pay high success fees to potential deal sources knowing that these fees will be charged to the fund's investments or investors, not to the fund manager themselves. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 7 (19m 9s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 141 These success fees may be paid to advisers who are a source of new transaction opportunities, and may influence which PE funds get to see which transaction opportunities. In-House Advice and Conflicts of Interest In some of the large funds, in-house advisory teams have been established to provide some of the functions that typically used to be bought in. These range from consulting teams to M&A teams working on the acquisitions for existing portfolio companies. These in-house service providers sometimes charge fees for their services exclusively to businesses owned by funds managed by their parent company. Not every private equity firm will charge fees for its operational teams, but as the fund managers also control many aspects of the board's decision-making (through the reserved matters that we discuss in the deep-dive into the equity terms later in this chapter), the potential for conflicts is material. Following the changes in regulation in 2010 when the Dodd–Frank Act in the US brought many PE funds under the regulation of the SEC, there were a large number of instances where fees charged by PE funds were found to be poorly justified, recorded, and accounted for. A number of firms were heavily fined by the SEC for extracting fees from portfolio companies. This is an area of ongoing debate and scrutiny. In essence the argument of the critics is that PE fund managers control the companies that are owned by the investors in their funds. They also sell services to those companies. They can therefore extract value from the companies by requiring them to use in-house advisers. This is in principle little different to any corporation using in-house services that could be bought on the open market. A key difference is that the prices observed on the open market reflect the risks of contingent fee arrangements. If a fund charges 'market price' for in-house services, but has control of the contingent risks, they will make extra-ordinary profits in their in-house transaction service businesses. Company Auctions Preparation PreMarketing Auction Round I Auction Round II etc Negotiation Exclusivity or Contract Race? Completion Post Completion matters Most transactions will go through a process led by a corporate finance adviser. Over the years this process has evolved. We will describe here a typical auction process for a private company (or subsidiary of a public company). The process is not unique to private equity buyers, but it is important to understand. Many of the behaviours of PE funds in auctions are entirely rational and are caused by the process structure imposed by the vendors and their advisers. Figure 4.4 shows a typical sale process at a high level. We enlarge on the stages below, but what we are seeking to draw to your attention is the intensity of the workflows (signified Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 8 (22m 21s)

[Audio] Vendor / Sell Side Acquirer/Buy Side Process Organization Deal Initiation Process Pre Marketing First Round Site Visits Meet Management & Vendors Finalise finance Locked Box? Final negotiations with vendors Finalise negotiations with management Finalise transaction structure Draft 100 day plan based on Due diligence findings Due Diligence Providers presentations VDD reports Arrange Debt Offers Transaction Structure Mark Up SPA ISSUE ROUND II OFFER Review materials Valuation Bidding Tactics Issue Round I Bid Letter With Indicative Offer 1. Searching for potential transactions 2. Networking with potential deal sources 3. Analysing potential targets 1. Fireside Chats 2. Initial discussion with potential buyers 3. Sign NDAs 4. Appoint buyside advisers 5. Find relevant sector contacts in network Prospecting & Relationship building Information and Data Preparation Information and Data Preparation First Round Information and Data Dissemination Preferred bidder (s) selected Final negatiations Locked Box? Disclosure process Exchange contracts Transitional arragements Completion Accounts? Completian Money FLows to Vendors Final process letter Open Dataroom to bidders Draft SPA to bidders Site visits Management presentatians Receive round III bids Consider exclusivity Issue Information Memorandum Process letter Stapled Debt Offers Receive round I bids Evaluate and investigate bids Decide on Second Round Bidders Prepare Information Memorandum Vendor Due Diligence Reports Arrange stapled Debt? Vendor Due Diligence Draft Reports Key Findings Prepare management Presentations Pre Marketing Initial discussions with potential buyers Fire Side Chats? Issue 1 page teasers? Sign NDAs Build comprehensive data room Build financial model valuation Paper Agree marketing messages Appoint Advisers Agree transaction process identify potential buyers Draft timetable Preparation Pre-Marketing Auction Round I Auction Round II Negotiation Completion Post Completion matters Initiate 100 Day Plan Completion Accounts? Figure 4.4. A typical auction sale process Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 9 (24m 49s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 143 by the darkness of the colour scheme) and the relative amount of preparation by a vendor and compressed time for a putative purchaser. The vendor side has intense work leading up to the launch of the process, and becomes more reactive as the process unfolds. The potential purchaser, including a private equity house, benefits materially if they have researched and identified the potential acquisition before the process starts. This explains why so much of the time of the senior partners in PE houses are spent networking with people who may give valuable insights into transactions, and why so much junior resource is invested in searching out and analysing potential acquisitions long before they come to market. Once in the transaction process, the vendor will want a swift route to completion at the highest valuation. The purchaser may well want the maximum amount of time to assess the business. Time is often the best form of due diligence. The attractiveness of the target and the competitiveness of the process will usually determine who wins this debate. What Are the Objectives of the Sale Process? The sale process seeks to efficiently and confidentially explore the universe of potential buyers. Corporate sales are transactions involving large amounts of public and private information, some of which is commercially very valuable. The process attempts to make a market by carefully transmitting and receiving information from potential seller to potential buyer. If the buyer does not have sufficient information to value the business, the process will fail. It is a classic 'lemons' problem of the type described by George Akerlof (as mentioned before in the context of syndication). If the seller reveals too much information, potentially including the fact that the sale is being contemplated, the commercial damage to the business can be extensive. The skilled adviser manages this information dynamic whilst building a competitive market to attempt to deliver an optimal mix of risk and return to the seller's shareholders and other interested parties. Preparation Pre-Marketing The adviser will prepare and communicate an initial information package to enable potential buyers to make an indicative offer for the business. Based on these offers and their own insights, a limited number of potential purchasers will be given more extensive information to make a final offer, subject to contract. The contract negotiations will lead to an exchange of the contract and finally a completion of the deal. We expand upon the nuances of this broad process below. Confidentiality: What Is an NDA? An NDA is a non-disclosure agreement or confidentiality agreement. It defines the obligations of the parties when they share private information and the remedies if that Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 10 (27m 56s)

[Audio] 144 Private Equity Demystified information is leaked or misused. Litigation under NDAs in private equity is surprisingly rare in Europe. It is however the first legally binding contract between potential vendors and buyers and the negotiation of its terms sets the tone of the legal negotiations to come. There have been attempts by various organizations to standardize NDAs in auction processes, but they are still often a bone of contention. When funds were small generalists it was unlikely that any material commercial advantage was gained by a private equity fund having access to any particular transaction. As PE funds have grown and specialized, the importance of NDAs and confidentiality more broadly has grown. Today most PE funds have sector preferences and are active participants in the M&A landscape in those sectors. An NDA can be anything from one page to a multi-page contract, but essentially it has a number of parts: first, it defines what confidential information is. secondly, it limits and defines who has the right to view the information and for what purpose. This will usually include provisions allowing the recipient to reveal information if required by certain laws; thirdly, it gives a process to store and recover the information. It then gives the broad basis on which the information is provided and how any remedy will be calculated if the agreement is breached; finally, it gives a time limit for the agreement and what legal jurisdiction it is covered by (e.g. US or UK law). What Are Fireside Chats? You will notice from Figure 4.4 that on the sell side a great deal of work is preparation for the sale process. These preparations include the identification of potential buyers and may also include extensive pre-marketing to potential key buyers. One of the most valuable pieces of contact that a buyer can have is with the management team of the business. This is sometimes arranged in an informal meeting called a 'fireside chat'. The management, usually chaperoned by the vendor's advisers, meet with potentially interested parties before the launch of the formal process. Fireside chats are very important ways to signal interest to buyers and sellers and to start to transmit informal and unstructured information to both sides. What Is an Information Memorandum (IM)? When selling a business there is a balance to be drawn between revealing sensitive information to competitors and allowing interested buyers to know enough to form a valuation that they can deliver. To ensure a level playing field and bound the information set, information memoranda are usually prepared. These are usually a highly professionally produced financial brochure putting forward the opportunity in its best light. The IM is typically produced by the vendor's corporate finance advisers in collaboration with the vendors. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 11 (31m 13s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 145 The IM will contain enough information on the business to allow a bidder to make an informed offer, subject to due diligence and contract, in the first-round bidding auction. Typically, it will include, at a minimum: (1) Product/service analysis; (2) Analysis of the market(s) of the business; (3) Strategic and competitor analysis; (4) Operational analysis; (5) Organization structure; (6) Historical financial performance and projections; (7) and many more options specific to the business, its circumstances, and those of the potential purchaser. The IM is a key sales document that will form the basis of negotiations. Amongst the most important figures in the plan are often the historical and forecast EBITDA. What Is EBITDA? As EBITDA—Earnings (profit) before Interest, Taxation, Amortization and Depreciation— has become so central to the way that corporate finance is discussed we examine it more fully in Chapter 5. Briefly: depreciation is the gradual recognition of the costs of fixed assets to reflect their deterioration over time in the company's profit and loss account (earnings statement); amortization is the recognition of the cost of intangible assets in a company's profit and loss account. It can be thought of as being essentially very similar to de pre ciation. To a first approximation, amortization is the depreciation of intangibles, although there are differences outside the scope of this work. EBITDA is intended to show the profitability of a business over a period of time disregarding how the business is financed. EBITDA can therefore be related to enterprise value, which, as we will discuss in Chapter 5, is what private equity is all about. What Are EBITDA Multiples? It is important to state clearly that EBITDA does NOT cause value. Value is determined by supply and demand. In financial assets (only) value can be estimated by looking at projected cash flows. This is because in financial assets demand is assumed to be a simple function of cash flows. You can almost define financial assets as being those things whose value is solely determined by their cash flows. EBITDA is a commonly used metric that emerged in the 1990s becoming one of the commonest ratios of profitability quoted in transactional corporate finance (Figure 4.5). Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 12 (34m 13s)

[Audio] 146 Private Equity Demystified EBITDA multiples compare enterprise value to EBITDA. EBITDA multiples are measures and descriptors of value, not causes. EBITDA mul tiples are how we talk about valuation, not how it is created. You can think of it as a price signal. If we told you that this book cost £10,000 a copy you'd rightly ask—Really! what is so special about this book to justify that price? Similarly, if you see a high EBITDA multiple you ought to ask yourself, what is so special about that company to justify that fancy valuation? The value of financial assets is determined by future cash flows, a forward-looking concept, so historic EBITDA multiples are questionable on that basis. Projected EBITDA multiples do not capture the complex interaction of volume, timing, volatility, uncertainty, and risk of expected future cash flows that are the causes of the demand for a financial asset. We return to this in Chapter 5. What Is Vendor Due Diligence (VDD)? Traditionally a potential buyer would make an offer and then commission advisers to complete due diligence on their behalf. This creates both delay and risks to the vendor. They will not necessarily see the due diligence before the final negotiations. To mitigate both negative factors, a vendor may commission and underwrite the costs of vendor due diligence (VDD). They arrange for an independent third-party expert to draft reports on the financial, market, and any other area that they deem critical to valu ation, usually prior to the release of the information memorandum to buyers. This means that the vendor should be aware of any potential major due diligence issues before sending out the information pack that will form the basis of initial offers and subsequent ne go ti ations. If there are any negative issues highlighted in the VDD, the vendor must decide whether to remedy them (if possible), or how to position the matter in the negotiation. These VDD reports will only be made available to final-round bidders under a suitable engagement letter from the report's authors. They will usually be updated prior to completion and whoever completes the transaction will have the final reports addressed to them. They will therefore be able to rely on them, meaning that they can potentially sue the authors of the reports if there is a material omission or error. 1970 0.0000000% 0.0000020% 0.0000040% 0.0000060% 0.0000080% 0.0000100% 0.0000120% 0.0000140% 0.0000160% 0.0000180% 0.0000200% 0.0000220% 0.0000240% 0.0000260% 0.0000280% 0.0000300% 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 EBITDA Figure 4.5. Google Ngram of the term EBITDA (1970–2010) Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 13 (38m 50s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 147 The disadvantages to the sell side of VDD are cost and a change in the timings of the sale process. If the purchaser already knows the business well and is comfortable with the risk, adding in a VDD process can unnecessarily delay a transaction. The disadvantages to the buy side are more complex. Having VDD may enable a buyer to rapidly understand a business in a granular way. However, nobody would choose to have their due diligence scope or engagement terms agreed with the provider on their behalf by the vendor. There are clear potential conflicts of interest for the VDD provider, who is instructed by the vendor at the start of the process but will have a duty of care to the purchaser at the end. As a result, for material areas particularly of CDD and FDD, buyers often appoint their own advisers to conduct independent analysis or top-up work. Auction Round I Auction Round II Negotiation Exclusivity or Contract Race? Completion How Does a Typical Private Company Auction Proceed? Most auctions have at least two rounds of bidding, but there can be many more. In public companies the regulator may step in to require a limit to the number of rounds of bidding to maintain an orderly market. Round I In round I indicative offers are sought from potential bidders. Bidders will receive the IM and very little other information. Preferred bidders may have had a fireside chat. The process will be governed by the vendor's corporate finance adviser who will issue a process letter explaining the time scales and requirements. Bids will be secret and will usually be non-binding letters of intent. The advisers and vendors will review the bids and decide how, and with whom, to proceed in the second round. Selection criteria will often be based on some combination of price and non-financial terms and deliverability (e.g. How serious is the bid? Is the bidder credible as a potential buyer? What is the bidder's reputation?) Round II Bidders will receive much more information, including the VDD reports and probably presentations by their authors, a full management presentation, and much greater dialogue with the vendor's advisers on any other matters of particular concern. The vendor's intention is to maintain competitive tension while enabling the purchasers to be in a position to make a final offer, subject only to a minimal number of outstanding matters. The vendor may issue a draft Sale and Purchase Agreement (SPA) and require the potential purchasers to mark up the draft. This enables the vendor to start to clearly understand the contract that is being created and the areas of contention. The potential purchasers must decide whether to incur the costs that accrue in these processes. In highly competitive auctions these are significant costs that, as we saw when discussing fees in funds in Chapter 2, are usually recharged to the fund's LPs. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 14 (42m 12s)

[Audio] 148 Private Equity Demystified Negotiation and Exclusivity or a Contract Race? Following Round II bids there will be an intense period of clarification and negotiation. It is important to understand that while price is the key thing that is being assessed, risks are also crucial to any decision. A high price with an onerous set of warranties from a litigious buyer may presage a long, costly, and ultimately value-destroying post-completion wrangle. A simple clean price with reasonable risk protections may be preferable. A great deal of the post Round II negotiations will be the interaction between price and transaction risks. A key decision is therefore whether or not to offer a bidder exclusivity. Exclusivity is a period during which the vendor undertakes to negotiate exclusively with only one party to seek to close the deal. Exclusivity offers the bidder the certainty needed to incur the costs of completing the deal. These include the opportunity costs of devoting management time to the deal as well as the pure financial costs of external advisers. As we discussed earlier, private equity funds traditionally drew down capital only to complete deals. Furthermore, one of their competitive advantages vis-à-vis trade purchasers is their transactional agility and quick decision-making. The ubiquity of the company auction is one of the changes in process that has led to the emergence of subscription line funding. Being able to offer to complete a deal rapidly in a short period of exclusivity can be a deciding factor in doing the deal. An alternative to exclusivity is a contract race between a number of potential buyers. This is a parallel negotiation with two (or potentially more) potential buyers that ends when one of them agrees and signs a satisfactory agreement with the vendor. Vendors maintain competitive tension to completion and should therefore extract most value. However, purchasers understandably hate contract races for both cost and transaction risk reasons. If the PE fund(s) are backing the incumbent management a contract race prevents relationship building that will be crucial post completion. This increases risk to the purchaser and therefore may actually reduce price. In the limit the bidder will simply walk away if the costs and risks are too high. Contract races also put significant burdens on vendors and advisers. Managing more than one bidder in the final negotiations of a deal is very expensive and time-consuming, as you have to duplicate many processes and negotiations for each bidder. Exchange Completion Post Completion matters Completion and Exchange When all matters are agreed, the SPA and all other contracts involved in the deal will be signed by all the parties and a copy given to each side. This is the point of exchange. Completion of the contract occurs when any pre-conditions of the contract (conditions precedent, or CPs, in the jargon) are met and the ownership of the business passes to the purchaser. There may be a gap between exchange and completion whilst the CPs are met, but generally all parties will seek to have a simultaneous exchange and completion. The commonest reason for a split exchange and completion are regulatory approvals required to transfer a business. In transactions that delist a public company (a P2P) there will a gap between the offer being posted and completion. This allows the public Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 15 (46m 3s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 149 shareholders to review and vote on whether or not to accept the offer and to allow the formal process to delist the business. We expand on completion mechanics below in the deep dive into the heads of terms. Do Private Equity Funds 'Chip the Price'? There is no peer-reviewed academic research on private equity bidding in auctions. We can only therefore examine incentives, experience, or hearsay. A two-stage secret bid auction as described above creates particular incentives when analysed by game theory. First, if only the highest bidders are taken forward, and all bids are non-binding, the most rational bid in Round I is the highest plausible bid. Bidding your true valuation and not being in Round II is not a winning strategy. Therefore, if the bidders are rational, you should expect to see high bids in Round I. Round II is more serious as all parties are incurring significant costs. In Round II the purchaser will need to balance the costs of an aborted transaction with the risks of exclusion due to underbidding. The incentives are still to bid strongly, but to seek to claw back as much value as possible if exclusivity is granted. This set of incentives has two consequences. First, it encourages overbidding in the first round, and subsequently in exclusivity following Round II, attempts to claw back value through price reductions. Therefore, 'price chipping' is what vendors and their advisers might expect to see from any rational bidder in a simple two-stage competitive auction. However, there is also an alternative multi-round game theory analysis. As private equity funds are often transacting with the same adviser community multiple times per year, frequent price chipping (without due cause from new information revealed or discovered after final bids) will create a negative reputation that vendor advisers will start to factor into their consideration of the credibility of future bids. Reputations like this get spread around and can be hard to shake off. This acts as some constraint on gratuitous price chipping for any PE firm that aspires to do multiple deals in a market. Do Auctions Increase Costs? The second impact of the auction process is that it encourages private equity funds to seek to use advisers on a contingent fee basis, as we discussed above. Contingent fees are higher than underwritten fees because the adviser concerned bears the risk of their client losing the auction and them not being paid. This therefore pushes up transaction costs to the winning bidder but reduces the abort costs to the losers. Overall, whoever wins the auction process has paid the highest costs, and these are passed on to the fund via the investment. This is in addition to the Winner's Curse that we talked about in Chapter 1. A Deeper Dive into a Private Equity Investment Agreement In this section we walk through the key terms that appear in most private equity investments. Our intention is to try to explain why the terms are present, not take any position Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 16 (49m 29s)

[Audio] 150 Private Equity Demystified on whether they should be in an agreement or to prescribe any particular outcome to a negotiation around them. A pro-forma detailed term sheet is at Appendix 4. This is representative of a mid-market UK buyout with management rolling over some of their investment. Not every transaction will involve a formal heads of terms document: on many occasions the process will skip straight to a formal draft of an investment agreement and a sale and purchase agreement. What Are the Key Contracts in a Private Equity Deal? There are many contracts to any deal, but if we simplify the situation to its most basic form, the essence will be clearer. Articles of association: As described above, a buyout involves setting up a new company (Newco) that will acquire the target and adopt its articles of association. In growth capital investments you may see an investment into a new class of shares in the existing target company. If so, the target company's existing articles of association will be replaced or amended to accommodate the rights of the new private equity investor. In this scenario the negotiation issues are similar, but rather than starting from a clean sheet with a new off-the-shelf company, you rewrite the existing contracts. Note that it is rare that a PE fund simply buys or subscribes for ordinary shares or common stock. One of the defining features of PE investment is the active controls that are embodied in the agreements between the shareholders. Here we will concentrate on the typical buyout structure, where a newco is established. The issues are fundamentally the same in growth capital and VC deals, but it is simpler to explain in a newco structure. An investment agreement is a contract between the equity investors in the acquiring company about the relationship between them (see Figure 4.6). The company may also accommodate many of the terms of the investment agreement directly into the articles of PE Fund Investment Agreement Mgmt NEWCO Articles of Association DEBTCO Articles of Association TARGET Articles of Association Loanstock Agreement Loan Agreement(s) Bank/ Fund Equity% Equity% 100% 100% Figure 4.6. Major contracts in a buyout Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 17 (52m 12s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 151 association of the company. Every company must have articles of association, but an investment agreement is not a required document. For our purposes we can think of the two documents as interchangeable. They key idea to understand is that there is a contract between the shareholders that is enforceable in law. There will also be a loan stock agreement (in Europe) between Newco and the private equity fund, governing the terms of its loans, just as there is between the banks or debt funds that fund the transaction. If the bank or other lenders lent directly to Newco, there would need to be an inter-creditor agreement (literally an agreement between creditors), but the way we have presented it above uses a Debtco which eliminates the requirement for that contract. There will be many more contracts, but these are the fundamental building blocks of the deal that might be covered in the heads of terms. We are ignoring the bank/debt fund loan agreement in this section; we will return to this in detail later. The sale and purchase agreement ( SPA) is the key contract between the sellers and buyers explaining what deal they have done (Figure 4.7). In a sense, this document is the deal that is being done, because this is the primary contract the courts will look to if there is any dispute. Most of the important items in these two/three documents should be addressed in the heads of terms, if only to acknowledge that the final position on the matter has not yet been agreed. The Heads of Terms A heads of terms is a non-binding agreement that sets out the key terms of the deal prior to starting to draft the formal contracts. The advantage of a formal heads of terms is the clarity it brings to all parties: you know broadly what you are signing up to before you have committed to incurring all the transaction costs. Equity% Equity% PE Fund NEWCO Articles of Association Mgmt TARGET Vendor TARGET Sale & Purchase Agreement Sales of Shares / Assets 100% Consideration Paid 100% Figure 4.7. The Sale and Purchase Agreement Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 18 (54m 39s)

[Audio] 152 Private Equity Demystified The disadvantage is that the search for clarity in what is meant to be a high-level summary often causes many unresolved issues to surface before either party is ready to agree them. This can result in a raft of outstanding items at the time when you are trying to create agreement and clarity. There is therefore the risk and tendency for heads of terms to become a prequel to the formal negotiation of the contracts that it is intended to be a short cut towards. Who Should Draft a Heads of Terms? There are two basic approaches: Either the principals draft the summary of their agreement between themselves and pass it to the legal teams to document, or the principals work with the lawyers to draft the document. If drafted by the respective legal advisers, the structure will often anticipate the contracts that will form the transaction. You can view this as a rough draft of the key planks of the emerging agreement. The fine details will follow, but the structure is loosely set. If it is not drafted in consultation with the legal teams, it will often not follow the structure of the formal documents, and may look much more like an indicative offer than a first draft of the contract. The Contents of a Typical Heads of Terms There are undoubtedly many deals that have been done 'on the back of a napkin' by de cisive entrepreneurs, but here we are dealing with a typical professional process involving an institutional investor. As we have tried to emphasize throughout, private equity firms have processes that they follow both to manage risks and, equally importantly for fund investors, to demonstrate management and control of risks. Even if a PE firm writes on the back of a napkin, their lawyers and investment committees won't, and the LPs who are funding a deal certainly won't expect them to. You should therefore expect to see rigour and process in any PE-backed transaction. Essentially a heads of terms answers three questions: who? what? how? Who are the people agreeing? What are they agreeing about? How does the process of implementing the agreement work? Who Are the Parties to the Deal? The parties to the sale and purchase agreement are, naturally enough, the buyers and the sellers. If the deal is a simple acquisition, there is nothing different about the SPA from any corporate sale. However, in buyouts there are often managers and manager/shareholders who are both sellers and buyers. If the business is a founder-owned business, the sale may be a partial sale to a new investor with the founders 'rolling over' some of their proceeds into the new company. Economically you can think of this as simply selling for cash then in stant an eous ly buying an investment in the newco with some portion of the proceeds (Table 4.1). There are knotty tax issues that we will deal with in the section on taxation of rollover in Chapter 5. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 19 (57m 55s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 153 What Is the Price? Definition and Consideration This is obviously a key term. As we have said, price in most private equity deals (except public to privates) is the enterprise value, expressed as the debt free/cash free value of the business with a normalized level of working capital. We explain the normalization later in this section. Carefully checking the definition of enterprise value is important. Some bidders will exclude corporation tax liabilities, arguing that these relate to past profits and are therefore rightly for the vendor's account. This is no different to any other creditor, and in any case many companies pay corporation tax in advance, but it is an argument that will still be made and needs to be checked. The price will include cash and any other consideration that is paid to the vendors. In this example we have chosen a relatively intricate deal that involves the receipt of cash, shares, and loan notes. This is common in secondary buyouts and partial sales to private equity funds. Assume that a PE fund offers to buy a business for £100m, paying £80m in cash and £20m in a mix of loans and shares (see Table 4.1). Note that the price is expressed as enterprise value, assuming a cash free/debt free balance sheet and a normal level of working capital. When Will the Price Be Paid? Exchange and Completion/Closing There are at least two points in a transaction when you might consider it to have been finalized. The first is when the final contracts are signed and exchanged between all the parties. This is final in the sense that there is nothing left to agree and all that should happen after signing is the execution of whatever the contract agrees will happen. This point is, perhaps unimaginatively, known as exchange. Completion (or, in America, 'closing') is the other natural end point of a transaction. It is the point at which the parties pay and receive the consideration and deliver the shares or assets to the purchaser. It is possible that there will be a gap between exchange and completion for an array of technical reasons. You might require an external approval before you can complete the deal. These might include regulatory approval in certain industries or approval by the rele vant competition authorities if there are potential concentration issues. In public-to-private transactions there is a formal process required to acquire all the shares in issue that can only take place after exchange of contracts. Table 4.1. Pro-forma transaction structure with a vendor rollover Resulting structure PE fund Vendor Total Shares 8 2 10 Equity % 80% 20% 100% Loans 72 8 80 Total −80 20 100 Cash flow −80 80 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 20 (1h 1m 30s)

[Audio] 154 Private Equity Demystified There may be other matters covered by the contract that happen after completion. These may be material to the transaction value, especially if there are completion accounts adjustments. This is covered below. Material Adverse Change Clauses (MACC) and Reverse Termination Fees If there is a gap between exchange and completion the purchaser will prefer to have the option to withdraw before completion, whereas the vendor will want complete certainty that once any CPs are satisfied completion will happen automatically. A material adverse change clause (MACC) is a wide-ranging condition that allows the purchaser to pull out of the deal if the has been a material adverse (bad) change in the circumstances of the deal. MACC clauses are common in North America but much rarer in the UK; their use varies across the rest of the world. Some vendors seek to protect themselves using a 'reverse termination fee' payable by the purchaser if they pull out of the deal. The full broad-ranging details are beyond our scope, but it is worth drawing attention to what happened in the global financial crisis in the US. In a number of large buyouts including Huntsman, Acxiom, and Sallie Mae, the private equity funds sponsoring the deal chose to pay the termination fee and invoke the MACC clause to withdraw from the deals. They cited the performance of the businesses and their prospects, not the crisis itself. After the crisis it was reported that average reverse termination fees increased from around 3.0 per cent of the equity value to 4.0–8.0 per cent of the equity value.1 MACC clauses are not required, and many European vendors will not accept them. The vendor wants certainty and will usually require exchange to be wholly unconditional. In most private deals the issue is avoided entirely by ensuring that exchange and completion happen at the same time: you sign, and you pay the consideration contemporaneously. What Is the Process for Ensuring that the Seller Has Delivered What They Said They Were Selling? Having agreed to pay the consideration the purchaser will want a method to verify that they did indeed get what they agreed to acquire. If there is any difference, there will be some process to address the difference (or not as the case may be). In a heads of terms this is a sensitive issue. 1 New York Times, 2 May 2012. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 21 (1h 4m 17s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 155 EBITDA Multiples and Minimum Net Assets You will see a variety of ways to define the price. They will almost always state that the price is based on delivering some financial metric—usually EBITDA—in a particular timeframe. This signals clearly that EBITDA is going to be one key number that is under scrutiny in due diligence between the heads of terms and completion. The rule of thumb is that if EBITDA falls the price will probably fall, usually by the EBITDA multiple that is being paid. If EBITDA rises it is much harder, but far from impossible, to get an acquirer to increase the price. You may also see an assumed level of net assets as a target metric. If net assets are less than the agreed amount there will be an adjustment to the price to make good the lost assets. Note that EBITDA results in a much higher reduction in consideration than a net assets target. Also note that you should not pay twice: if EBITDA is reduced it is likely that net assets will also fall. Mechanisms to Verify the Assets and True-Up the Consideration Completion mechanics vary markedly between different deal types and different geographies. Public Company Takeovers (P2P) In a public company takeover, completion is very straightforward, and there is no process to adjust the consideration after completion. You bid for the shares and if the shareholders accept you get the shares. You must be unconditional in all respects when you make the offer. You cannot have any process to check the assets or profits after you take control. Private Company Takeovers Most private equity deals are private company transactions. In a private transaction you will often, but not always, have a mechanism to confirm profitability and net assets either just prior to, or just after completion. What Are Completion Accounts? Most contracts for the purchase of private companies (but not public takeovers) will have a mechanism to check that the assets and liabilities acquired are substantially the same as the accounting records say they are. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 22 (1h 6m 44s)

[Audio] 156 Private Equity Demystified All accounts involve judgements on the part of the people preparing them. There is therefore often a negotiation around the basis on which the accounts are prepared. This is especially important when the acquirer and the vendor use different sets of accounting principles. If a US acquirer has assumed USGAAP (US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) but the vendor has based their calculations on their own internal application of IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) the possibility for a long technical debate is obvious. The appropriate standards therefore need to be agreed if completion accounts are to be used. The contract will have a minimum net asset amount that the vendor is to deliver to the purchaser. To check whether this has happened, the accountants of the vendor, or much more usually the acquirer, will prepare a balance sheet at an agreed date. The contract will state a mechanism to adjust for any material discrepancy. This is the so-called £-for-£ net asset adjustment. Some of the consideration may be held in an escrow account until the completion accounts are agreed. An escrow account is a bank account created by an adviser to hold cash in suspense until any disputes have been agreed. Once they are agreed the amount will be released, less any deductions for the net asset adjustment, to the vendors. All of this process and the negotiation of it takes place after completion of the transaction. The advantage of completion accounts lies mainly with the purchaser. Their accountants usually prepare the first draft of the accounts and will therefore tend to favour the buyer. The disadvantages are the protraction of the M&A process beyond completion. This is as important to buyer and seller. This mechanism is common in the US, but has fallen in use in Europe due to the emergence of the locked box completion mechanism. What Is a Locked Box Completion Mechanism? Locked Box Process STAGE 01 STAGE 02 STAGE 03 STAGE 04 STAGE 05 STAGE 05 Due Diligence Heads of Terms Negotiate Contracts Locked Box Negotiation Completion In Europe (but not in the US) there has been a move away from completion accounts after the deal completes. In their place a date is agreed prior to completion on which the net assets will be verified and valued. This is the locked box date and is usually the month end prior to completion. After the locked box, the vendor warrants not to make any distributions or payments to the shareholders or any other party other than in the ordinary course of trading. All cash generated by trading after the locked box date is for the purchaser's Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 23 (1h 10m 8s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 157 account, although it is customary to have a negotiation about a fixed interest charge to the vendor to cover the period. The impact is to eliminate the post-completion negotiation of completion accounts. Normalized Working Capital One of the risks of agreeing a price based on enterprise value is that the vendors are incentivised to minimize debt and maximize cash on the day of completion or the day of the locked box closing. To illustrate the issue by reductio ad absurdum, a vendor could stop investing in capital expenditure, stop paying suppliers, and aggressively start to collect outstanding debtors to the extent that customer relationships were damaged. This is an intricate and technical area where lawyers and accountants usually do the detailed work, but the essence is easy to follow. All businesses have some degree of seasonality, if only reflecting quarterly rent payments or annual or semi-annual tax payments. When bidding for a company a buyer will want to ensure that the business has a normal level of working capital. If it is too low, the purchaser will have to put money into the business to fund the decrease. If it is too high the vendor will have funded the working capital and when it reduces the purchaser will receive a windfall cash inflow, effectively a reduction in the price paid. To avoid this and avoid having to do full completion accounts, a mechanism is often used that simply compares the working capital balance on the day of the locked box to the average over the full cycle. If the working capital is lower than the agreed average, the price is reduced. Conversely, if the working capital is higher, the price is increased. This can be very material in businesses like retail where in Western Europe and North America, Christmas accounts for a very large proportion of sales. One of the reasons that failing retailers are often put into insolvency just after Christmas, or on Christmas Eve, is because the working capital is at a minimum and the cash a maximum as stocks are low, sales have been high, and rent and tax payments are due in the new year. Information and Warranties in the Deal Process Three economists—George Akerlof, Joseph Steiglitz, and Michael Spence—shared the 2001 Nobel Prize in economics. Their work deals with information asymmetry (the study of the economic consequences on trade of one party having more information than another). The problem arises when you are selling a company in a particularly severe form. Companies are the most complex things that are traded. Selling a business may transfer all the future and historical risks and rewards to the new owner. If you cannot persuade the new owner that the net value of those risks and rewards is quantifiable and positive, you probably won't sell the business. This is one of the commonest areas in which M&A transactions fail. A corporate sale process needs a comprehensive strategy of managing and transmitting information. If it does not have one, transactions may fall apart later in the process. In the late stages of any deal, purchasers narrow the information asymmetry, usually via due Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 24 (1h 13m 35s)

[Audio] 158 Private Equity Demystified diligence. If the purchaser finds that what they were told at the start of the process is not true and the reality is worse, they will reduce price or pull out. What Are the Different Negotiating Positions regarding Warranties? There are a number of ways to deal with information asymmetry. No access, no warranties: the simplest and crudest solution is to ignore the issue entirely. A vendor can provide limited data and tell purchasers to rely on their own judgment. In essence, this is what happens in an unsolicited hostile takeover, and may well be the reason that so many hostile approaches subsequently turn out to be failures. Transmit information and/or give warranties: to bridge the asymmetry you can either transmit information (under a suitable confidentiality agreement) or agree to take residual risks away from the purchaser by giving warranties. At the extremes, the negotiating positions are either Full access, no warranties: 'We will give you access to do whatever due diligence you like, but we are not warranting anything'; or Full warranties, no access: 'We will warrant that the information we give to you is materially correct, but you are not getting any more access than that'. The trade-off matrix is identical to the one we described for the disclosure/warranty trade-off. In reality a number of solutions have emerged to alleviate this sharp distinction. Information memoranda, fireside chats, vendor DD, and management presentations –350 –300 –250 –200 –150 –100 –50 – 50 100 150 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 $/£000s Month Seasonality and Working Capital Adjustment Working Capital Adjustment Average W.Capital Net Current Liabilities Figure 4.8. Seasonality and average working capital balance Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 25 (1h 16m 28s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 159 transmit information and reduce asymmetries. Disclosure letters and warranties also transmit information as they provide comfort to buyers. The approach to this broad question needs to be decided early on in any sale as it flows through the entire transaction approach and materially influences the form of legal agreement that will emerge at the end of the process. Each contract will have its own warranties. The SPA will have warranties from seller to buyer (and possibly vice versa). The investment agreement will have warranties from the management team to the investors. Seller Warranties The general principle in corporate transactions is caveat emptor ('buyer beware'). There are protections against fraud and misrepresentation, but overall the buyer needs to rely on either their due diligence process or warranties to protect them. Warranties are statements that the purchaser is entitled to rely on when they are buying an asset. They are written into the contract. They can be specific (e.g. 'The company owns all the assets listed in the fixed asset register dated dd/mm/yy') or general (e.g. 'The shareholders do not know of any reason why the vendor should not proceed with the transaction'). The definition of knowledge can also be crucial. It might mean anything from what a reasonable person ought to know, if they had carefully checked each warranty and all the information disclosed, to what a person actually does know, having not had time to do a review of any kind. Agreeing the definition of knowledge is an important detail. If any of the warranties turns out to be incorrect, the purchaser has a claim under those warranties. Broad Vendor warranties protect Purchasers Narrow Vendor Warranties protects Vendors Higher Risk for Vendors Broad Sweeping Warranties High Due Diligence Access Low Due Diligence Access Narrow and Limited Warranties High Risk for Acquirers Figure 4.9. The warranty/due diligence trade-off landscape Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 26 (1h 18m 44s)

[Audio] 160 Private Equity Demystified Warranty to Title: A Note on Private Equity Firms One of the warranties that is always given is that the parties to the contract are the owners of the shares being sold. In fact, this (and the right to enter into the contract) is almost the only warranty that you can guarantee you will receive when buying a business from a private equity firm in Europe. It is different in the US, where PE firms will give warranties. In the past what starts in the US has come to Europe, but as we write there are still significant differences in the warranty positions reported by lawyers on the two sides of the Atlantic. As we have seen, PE firms are fund managers. They are investing other people's money alongside their own. The ultimate owners of the shares are therefore passive investors. PE managers can therefore argue that they do not own the shares and the LPs who do own them cannot give warranties for commercial reasons. The specific reason given is lack of information. The investors delegate all day-to-day decisions to the PE fund manager. They therefore cannot reasonably warrant matters that they do not necessarily know anything about. They are, in effect, in the same position as if they were holding public company shares, and public company sales routinely complete without warranties worldwide. Management Warranties When transactions were initiated and led by managers who wanted to lead a management buyout, it was wholly reasonable to expect the managers to give warranties to the incoming investors. As the market matured and transactions have become auctions where management are no longer in the driving seat, they have become less central to the transaction. As a rule of thumb, the further management are away from controlling the deal, the weaker any warranties will be. If managers do not hold or receive equity in a deal they will generally not be required to give warranties. It is argued that management warranties are immaterial in the finances of the transaction but crucial in bridging the information asymmetry that exists between buyer and seller. The purpose of the management warranties is therefore usually to encourage disclosure rather than to have any financial recovery in the event of a warranty claim. Financial recovery is usually via the SPA. How Do Warranty Limits Work? Jointly or Severally? The purchaser is concerned to be able to get their money back if there is a warranty claim. They therefore want to be able to have a single lawsuit against all the vendors jointly. The vendors on the other hand will usually wish to deal separately with their own particular warranties and will wish to give the warranties severally (i.e. on their own). There will therefore be a wrestle over whether any or all warranties are individual and several or are collective (joint and several). By bringing together the vendors there will be Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 27 (1h 21m 56s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 161 a need to discuss how any liability is shared amongst the warrantors. This is particularly important where one warrantor is very wealthy and the others are not, or where some of the warrantors know more about a particular aspect of the business than the others. For example, should the sales director be expected to warrant anything about the way accounting principles are used in the way the management accounts are prepared? De Minimis/Throwaway Limits One of the risks of giving any warranties is that it invites claims against them. To stop spurious claims there is always a limit below which any individual claims are ignored. This is the de minimis or throwaway limit. It stops a vexatious acquirer from starting a swathe of spurious claims against a vendor. For example, you cannot sue if it turns out that the number of paper clips or pencils is less than the company records suggest (unless of course it is a paper clip or pencil manufacturer or distributor). Threshold or Basket Limit In addition to the de minimis, there will be a basket limit below which any group of claims is considered not material. Only once the basket limit is breached can any claim be made. The vendor therefore wants a high de minimis and a large basket limit, whereas the purchaser will tend towards more caution when agreeing the limits. There is often a negotiation about whether the basket 'tips over' or 'overflows'. A tipping basket gives the claimant the right to the total amount if a claim is made, including the basket. An overflowing basket only gives the right for the claimant to claim the excess above the basket limit. The difference can be material. Is the Claim over the de minimis Limit CLAIMS BASKET POTENTIAL CLAIM Are Total Claims Greater Than the Basket Limit NO CLAIM Start NO YES NO YES Figure 4.10. The warranty claim process.

Scene 28 (1h 24m 0s)

[Audio] 162 Private Equity Demystified Limit of Warranty Claim There will usually be an upper limit on the total value of any warranty claim. The vendors will want it to be low. The purchasers will argue that they should be able to get all their money back if the loss is greater than the amount paid. One complexity is that the vendors will have paid tax on their proceeds and therefore may not have the total amount of consideration even if they simply banked all the consideration in cash. A negotiation ensues. Time Limits of the Warranties There will also be a date beyond which claims can no longer be made. This is often made by reference to an anniversary of a time after a certain number of audits have been completed. The idea is to draw a line under the deal but to allow the purchaser a reasonable amount of time to establish if there are any potential claims. Tax Deed and Tax Indemnity It is normal for a vendor to give a tax indemnity. This requires the vendor to be responsible for any tax matters relating to the period before completion on a £ for £ basis. The deed simply means that the purchaser does not need to show loss before being recompensed for any historical tax costs not provided for. Warranty Insurance Since the early 1990s an array of insurance products has developed that are designed to provide cover against potential warranty claims. Warranty insurance protects the warrantor against the unknown, not against the known. Because insurance contracts are entered into on the basis of full disclosure to the insurer, you cannot achieve a position that insures against false warranties. In the words of Donald Rumsfeld, warranty insurance only covers known unknowns and unknown unknowns (see fig 4.11). Unknown Unknowns Matters of which you are unaware Known Unknowns Matters you are aware of, but you do not know about Known knowns Matters you are aware of and that you know about Figure 4.11. Warranties and information.

Scene 29 (1h 26m 8s)

[Audio] A Private Equity Transaction 163 When it was first developed there was some resistance to the idea of reducing the vendors' and management's exposure under the warranties. The argument was that insurance weakened the threat that was being used to force disclosure of all bad news prior to a deal completing. Warranty insurance is now common. It is usually paid for by the buyer. It benefits the vendors and the management team who are warranting as it reduces the risk and amount of any warranty claim against them. It also benefits the buyer as it makes a claim less politically difficult and reduces the risk of non-recovery (e.g. if the vendor has no money left when the warranty claim arrives). Disclosure Prior to completion the vendor will prepare a disclosure bundle to be given to the purchaser. This disclosure letter will include any matters that the vendor wants to bring to the purchaser's attention before completion. Anything in the disclosure bundle is deemed to be known by the purchaser before they entered into the deal. They therefore cannot sue for anything that has been fully and fairly disclosed (see Figure 4.12). There is therefore a tension and trade-off between the interests of the vendors and pur chasers that needs to be reconciled. Vendors and management always wish to disclose widely. They may argue that anything that the purchaser has discovered in their due diligence is deemed to be disclosed and that everything that has been made available to them is also disclosed. Purchasers will not usually accept these sweeping disclosures, in part because they have to be able to analyse the disclosure bundle to ensure there are no bad surprises. Is there a breach of a Warranty Has the Breach Been Disclosed NO CLAIM CLAIM BASKET YES YES NO NO Figure 4.12. Disclosure and warranty claim process Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/book/31976/chapter/267726442 by King's College London user on 22 October 2023.

Scene 30 (1h 28m 12s)