CamScanner 06-03-2022 22.24

Scene 1 (0s)

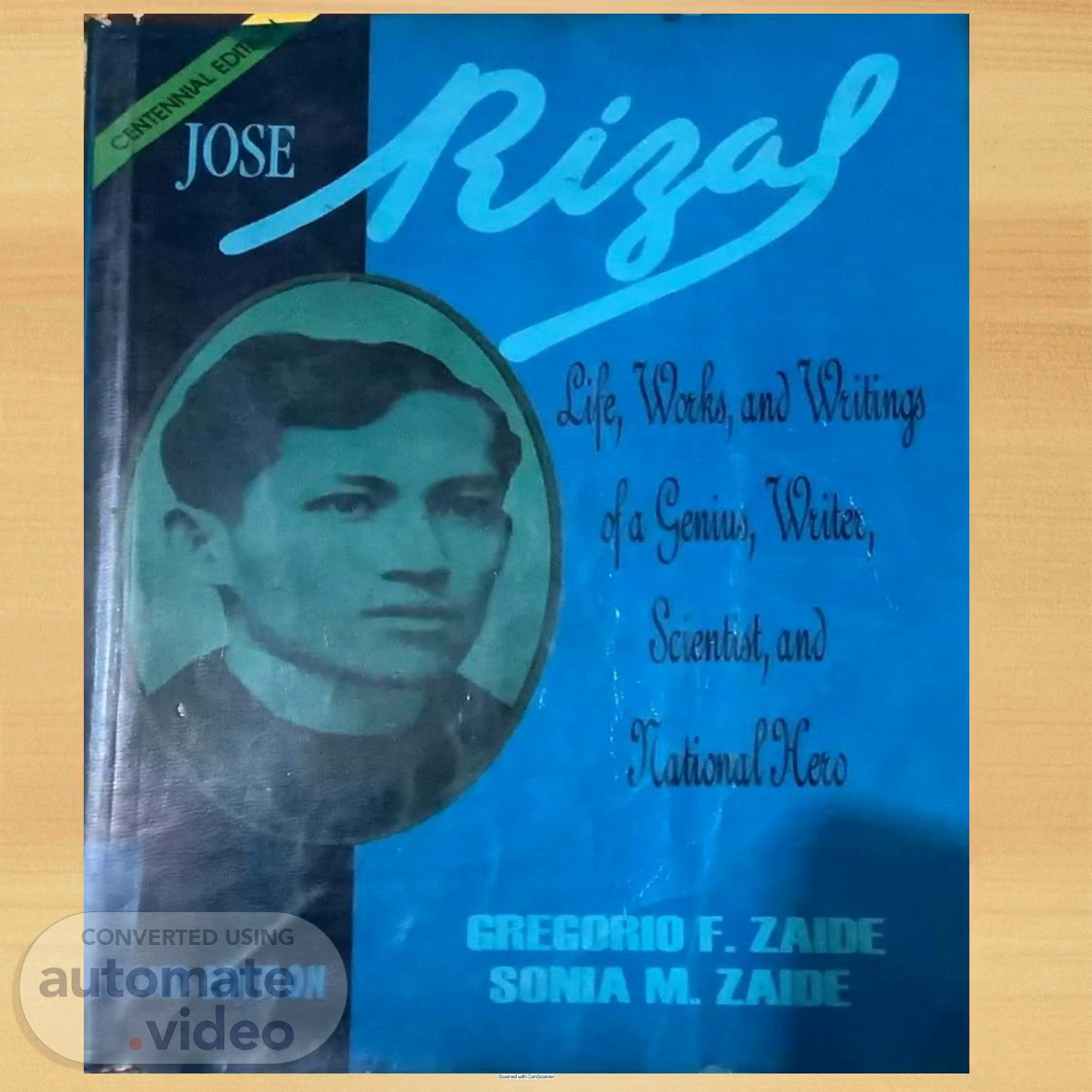

JOSE SCäA ra zw-.

Scene 2 (7s)

TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE . PREFACE TO THE CENTENNIAL EDITION . 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 14 15 16 17 Prologue: Rizal and His Times . Advent Of a National Hero . Childhood Years in Calamba Early Education in Calamba and Bifian Scholastic Triumphs at Ateneo de Manila, (1872-1877) . Medical Studies at the University Of Santo Tomas (1877-1882) In Sunny Spain (1882—1885) . Paris to Berlin (1885—1887) Noli ble Tangere Published in Berlin (1887) . Rizal 's Grand Tour of Europe with Viola (1887) . First Homecoming (1887-1888) . In Hong Kong and Macao (1888) . Romantic Interlude in Japan (1888) . Rizal's Visit to the United States (1888) . Rizal in London (1888-1889) Rizal 's Second Sojourn in Paris and the Universal Exposition of 1889 . In Belgian Brussels (1890) Misfortunes in Madrid (1890-1891) 1 9 20 27 78 88 105 113 124 128 137 142 153 167 176.

Scene 3 (39s)

18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Biarritz Vacations and Romance with Nelly Boustead (1891' El Filibusterismo published in Ghent (1891) Ophthalmic Surgeon In Hong Kong (1891-92) Second Homecoming and the Liga filigina Exile in Dapitan (1892-96) Last Trip Abroad (1896) Last Homecoming and Trial Martyrdom at Bagumbayan APPENDIX A APPENDIX B APPENDIX C APPENDIX D APPENDIX E APPENDIX F NOTES PROLOGUE: APPENDICES Who Made Rizal Our Foremost National Hero. and Why? By Esteban A. de Memoirs of a Student in Manila by p. Jacinto To the Young Women of Malolos The Indolence of the Filipinos The Philippines A Century Hence Last Farewell RIZAL AND HIS TIMES SELECrED BIBLIOGRAPHY INDEX 183 190 213 251 323 333 365 419 426 PREFACE This new book on Rizal is primarily written tu replace the previous college textbooks on Rizal by the senior author, namely, Jose Rizal: Life, Works and Writings and Rizal: Asia's First Apostle of Nationalism, published in 1957 and 1970, respectively. While these two Rizal books have been widely used both here and abroad, the present authors feel that there is need to write a new Rizal book on account of the fact that new materials on the national hero's life have surfaced in history's limelight, making the older editions rather obsolete or inaccurate in certain passages. For instance, the International Congress on Rizal, which was held in Manila on December 4-8, 1961 to commemorate the centennial anniversary of the national hero's birthday, unco- vered many hitherto unknown facts on Rizal. Since then, more Rizal materials have been researched by Rizalist scholars in foreign countries, particularly Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan, England, France, Spain, and Germany. It is delightful to know and to write the biography of Rizal for two reasons. He was an exceptional man. unsurpassed by Other Filipino heroes in talent, nobility Of character, and pat- riotism. And, secondly, his life has been highly documented, the most documented in fact, of all the heroes in Asia. Possessing a keen sense of history and an aura of destiny, Rizal himself kept and preserved for posterity his numerous poetical and prose writings, personal and travel diaries, scientific treatises, and hundreds of letters written to, and received from, his parents, brothers, sisters, relatives, friends, and enemies. With these preserved documentary sources, any biographer, with not much difficulty may weave his life story. To climax his herpic life, Rizal welcomed his execution on December 30, 1896 with serene courage, knowing that he was going to die in a blaze of glory — a martyr for his people's freedom. This book is a product of more than three decades of extensive research work on Rizal's life, works and writings in the Philippines and in foreign countries where he sojourned. We have included in this book certain episodes or incidents in the.

Scene 4 (1m 45s)

Me v—Riul tiographers have either missed in tw i*resting Rizalian are the following: t. in to Pakil. Laguna, was fasinated by turumba. a religious publkly dancing and singing during the Maria 2. fun st«y 01 the Rizal-O&i-San romance in IS. real Rizal met her, to after Rizal had kit her. 3. Rizal (a Japanese patriot). 4. HiNya Park ixi&nt in March I in Whkh Rial that the principal rnernt*rs of the Imperial giving tlr weekly public uncertS , Frio rm- ing exquiüte Western dassical music. vere actually Filipino — early of "brain drain- of talents n.untri—). 5. Rizal student Etivist participated in the stu&nt in Madrid, 6- Rial mt to obtain as Dcxtor of Meocitr. He practised medicirr using his in Mc&ine. 7. Rial sum»rta' in the titter Spain-Germany Controversy ( over the ownership of the Carolinas and Palau arch*lagc. in the pacific. 8. Rizal worked as a proof-rea&r in a German pub Eshing c.y in Leipzig (1M). 9. Rizal was deported from Germany in 1 s.cted by Berlin as a "Y. 10. Rizal and Ecret *Kiety, R.D. L.M. tion of the Malays). II. ear duel t*tween Rizal and Lar&t (French. man) in 103. In u:mcltBion, we express our gratitude to the prestigious Rizalist biogaphers (including Retana, Craig, Palma, Guerrero, Joe Hernanda, Carl« Quirino, Esteban A. de Ocamp, and Fernan&t), works wc onsulted in the prep. araticm of •his Of Fial arntion is Professor for his valuable sugestions and the of his Rizaliana Collection. With his kind crrmission. we use as APPENDIX A his definitive e.ay "Who Jose Rizal Our Foremost National Hero, and Why?" to blast the myth that Rial was -an American-madc national trro-. GREGORIO F. ZAIDE SOMA M. ZAIDE papnian, L.aßma June 19,.

Scene 5 (2m 52s)

Boyan Lirn. cultivated entirely by Guard* Ova. Ihe last hated syrntx»l of Spanish tyranny v" Guarüa Civil (Constabulary) which was created by the Royal Ikcree of February 12. 1852, as amended by the Royal 01 March 24, for the purvx»e of maintaining internal or&r in the Philippines. It was patterned after the and "II-drxvlined Guardia Civil in Spain. Wble it is true that the Guardia Civil in the Philippine ren&red meritorious services in suppressing the bandits in the later became infamous for their rampant as maltreating inncx•ent Frople, looting their and valuable belongings. and raping helples Both offxers (Spaniards) and men (natives) were ill- undisciplined. unlike the Guardia Civil in Spain who and well-liked by the r»pulace. Rin] "tuany the atrcrities committed by Civil on the Calamba folks. He himself and his of the brutalities of the lieutenant of Gvil. It natural that Rizal directed his stinging satire apiM Guaria Civil. Through Elias in Noh Me Tangere. he Guarüa Civil as a bunch of ruthless ruffians and "IRI-securing honest men-. to *ove mihtary organization by having it who gnssessed education and gex»d were con«ious of the limitations and respon- and rxm•cr. "So much rx»wer in the hands filled with passions. without moral training, satd through Elias, "is a weavx»n in Chapter 1 Advent of A National Hero Dr. Jog Rizal is a unique example of a many-splenüred genius who came the grcate•a hero of a Endowed b' With versatile gifts. he truly ranked With He was a physician (ophthalmic surgeon). dramatist. essayist. novelist. historian. architect. pa.ntcf , ruWor. e&atm. linguist, musician, naturalist. ethnoiogN. farmer businessman. economist. geographer. c. •Io-grar*rr. liophile, philologist. grammarian. folklorist. trn• lator, inventor. magwtan, humorist. sattrN. sm»rtsman,' traveler. and prophet. Aryne and all he was a hero and m»litical martyr Who h" Ide thc redemption 01 his oppres*-d No relaimed as the national hero 01 The Birth ot a Hero. Jose Rizal •as night Of June 19. tn Calamba. Laguna Provitre. "is during the delivery of ho tng As meny years later in his student -l on 19 June. and trfore full me»n It was a Wedtrsday and my this vale Of tears would have my ide not vowed to the vtrpn 01 'o by way ot pdgnmage was barmrd m 22. three days by Who was a Batho Pedro native Oi CAamba vas a &votee thc.

Scene 6 (3m 58s)

RIZAL: u". WORKS AND W" 'TINGS During the christening cerernony Father Collantes Was by the baby's big head, and told the of the family who were present: "Take care of this child, for someday he "ill trcome a great man." His words proved to prophetic. as confirmed by subsequent events. The baptismal certificate of Rizal reads as follows: "l, the undersigned parish priest of Calamba, certify that from the investigation With authority, for replacing the parish tx»oks which were burned Septemtrr 28, 1862. to be found in Docket NO.' Of Baptisms, p. 49, it appears by the sworn testimony Of comB:tent witnesses that JOSE RIZAL MERCADO is the legitimate son, and Of lawful Of Francisco Rizal Mercado and Dona Teodora Realonda, having Iren baptized in this parish on the 22nd day of June in the year by the parish priest Rev. Rufino Collantes, Rev. Pedro Casanas his g'xifather. — Witness my signature. (Signed): LEONCIO LOPEZ It should noted that at the time Rizal was born. the governor generol of the Philippines was Lieutenant-General Jose Lerner-y. former senator of Spain (member of the of the Spanish Cortes). He governed the Philippines from Feb. ruary 2. to July 7, 1862. Incidentally, on the same date of Rizal's birth (June 19, MI). he sent an official dispatch to the Ministry of War and the Ministry of Ultramar in denouncing Sultan Pulalun of Sulu and several powerful Moro datus for fraternizing with a British consul. Among his achieve- menb as governor gcncral were (I) fostering the cultivation of cotton in the provinces and (2) establishing the politico-military governments in the Visayas and in Mindanao. Rizal's Parents. Jose Rizal Was the seventh of the eleven children of Francisco Mercado Rizal and Teodora Alonso Realonda. hero's father, (181"898) was born in Bihan, Laguna. on May 1818. He studied Latin and Philosophy at the college of san Jose in Manila. In early man. hood, following his parent's death, he moved to Calamba and became a tenant-farmer Of the Dominican-owned hacienda. He was a hardy and independent-minded man. who talked less and worked more, and was strong in body and valiant in spirit. He died in Manila on January 5. 1898, at the age of 80. In his student memoirs, Rizal affectionately called him "a rncxlel of fathers". 2 Dona (1826-1911). the hero's mother, was tx•rn in Manila on NovemtEr 8, 1826 and was educated at the College of Santa Rosa, a well-known college for girls in the city. She was a remarkable woman. possessing refined culture. literary talent, business ability, and the fortitude of Spartan women. Rizal lovingly said of her: "My mother is a woman of more than ordinary culture; she knows literature and speaks Spanish than l. She corrected my mierns and gave me good advice when I was studyine rhetoric. She is a mathematician and has read many Dona Teodora died in Manila On August 16, 1911, at the age of 85. Shortly before her death. thc Philippine government offered her a life She courteously rejected it saying. "My family has never been patriotic for money. If the government has plenty of funds and does not know what to do with them. better reduce the taxes." Such remarks truly her as a worthy mother of a national hero. The Rizal Children. God blessed the marriage of Francisco Mercado Rizal and Tec-Elora Alonso Realonda with eleven chil• dren — two boys and nine girls. nese children were as follows: I. Saturnina — Oldest 01 the Rizal chil- nicknamed Neneng: married Manuel T. Hidalgo Of Tanawan , Batangas. 2. Paciano (1851-19M)) — Older brother and :onfidant Of Jose Rizal; after his younger brother's execution. he joined the Philippine Revolution and a combat general; after thc Revolution, he retired to his farm in Banos, where he lived as a gentleman farmer and died on Avil 13, 19M), an old bachelor aged 79. Hc had two children by his mistress (Sevcrina Deccna) — a and a girl. 3. Nircisa ( 1939) — her name was Sisa and she married Antonio (nephew 01 Father LA'ncio LOFz), a school teacher Of Morong- 4. Olimpia ( 1855-1M) Ypia was her name; she married Silvestre Ubaldo. a telegrapb osrrator from 3.

Scene 7 (5m 5s)

N mNØ 5. Lucia (1857-1919) — She married Mariano Her- of calamba. who was a nephew of Father Casanas. Hertx,sa died of cholera in 1889 and was denied Christian burial because he was a brother-in-law of Dr. Rizal. 6. Maria (1859-1945) — Biang was her nickname; she married Daniel Faustino Cruz of Birian, Laguna. 7. JOSE (1861-1896) — the greatest Filipino hero and genius; his nickname was Pepe; during his exile in Dapitan he lived with Josephine Bracken, Irish girl from Hong Kong; he had a son by her. but this baby-boy died a fcw hours after birth; Rizal named him "Francisco" after his father and buried him in Dapitan. 8. ConceFion (1862-1865) — her pet name was Con- Cha; she died of sickness at the age Of 3; her death was Rizal's first sorrow in life. 9. Josefa ( 1865-1945) — her pet name was Panggoy; shc died an Old maid at the age of 80. 10. Trinidad — Trining was her pet name; she died also an Old maid in 1951 aged 83. I I. Soledad ( 1870-1929) — youngest Of the Rizal chil• dren; her pet name was Choleng; she married Pantaleon Quintero of Calamba. Sibling relationship among the Rizal children was affection- ately cordial. As a little boy, Rizal used to play games With his sisters. Although he had boyish quarrels with them he respected them. Years later when he grew to manhood, he always called them Dona or Senora (if married) and Senorita (if single). For instance, he called his older sister "Dona Ypia," his oldest sister "Senora Saturnina," and his unmarried sisters "Senorita Josefa" and "Senorita Trinidad." Rinl's relation with his only brother Paciano, who was ten years his senior, was more than that of younger to older brother. Faciano was a second father to him. Throughout his life, Rizal respected him and greatly valued his sagacious advice. He immor- talized him in his first novel Noli Me Iüngere as the wise Pilosopo Ta»io. In a letter to Blumentritt, written in London on June 23, 1888, he regarded Paeiano as the "most noble of Filipinos" and •though an Indio, more generous and noble than all the Spaniards put together"4. And in a subsequent letter also written to Blumen- 4 tritt and dated London. October 12, 1888. he spqke of his beloved older brother, as follows: "He is much finer and morc serious than I am; he is bigger and more slim; he is not so dark; his nose is fine. beautiful and sharp; but he is bow-legged. Rizal's Ancestry. As a typical Filipino. Rizal was a product of the mixture of races. 6 In his veins flowed the blood of both East and West — Negrito, Indonesian, Malay. Chinese, Japanese, and Spanish. Predominantly, he was a Malayan and was mag- nificent specimen of Asian manhood. Rizal's great-great grand- father on his father's side was Domingo Laméo, a immigrant from the Fukien city of Changchow. who arrived in Manila about 1690. He became a Christian, married a well-to-do Chinese Christian girl of Manila named Ines de la Rosa, and assumed in 1731 the surname Mercado which was appropriate for him because he was a merchant. Spanish term mercado means "market" in English. Domingo Mercado and Ines de la Rosa had a son, Francisco Mercado, who resided in Birv.n, married a Chinese-Filipino mestiza, Cirila Bernacha, and was elected gobernadorcillo (municipal mayor) of the town. One of their sons, Juan Mercado (Rizal's grandfather), married Cirila Alejandro, a Chinese-Filipino mestiza. Like his father, he was elected governadorcillo of Binan. Capitan Juan and Capitana Cirila had thirteen children, the youngest being Francisco Mer- cado, Rizal's father. At the age of eight, Francisco Mercado lost his father and grew up to manhood under the care of his mÖther. He studied Latin and Philosophy in the College of San Jose in Manila. While studying in Manila, he met and fell in love with Teodora Alonso Realonda, a student in the College of Santa Rosa. •They v:ere married on June 28, 1848. after which they settled down in Calamba, where they engaged in farming and business and reared a big family. It is said that Dona Teodora's family descended from Lakan- Dula, the last native king of Tondo. Her great-grandfather (Rizal's maternal great-great-grandfather) was Eugenio Ursua (of Japanese ancestry), who married a Filipina named Benigna (surname unknown). Their daughter, Regina, married Manuel de Quintos, a Filipino-Chinese lawyer from Pangasinan. One of Ahe daughters of Attorney Ouintos and Regina was BrigiAa, who married Lorenzo Alberto Alonso, a prominent Spanish-Filipino s.

Scene 8 (6m 11s)

NEAL: uæ WORKS mestizo of Bihan. neir children were Narcisa, TeÜra (Rizal's mother), Gregorio, Manuel, and Jose. Surnny Rizal. The real surname of the Rizal family was Mercado, which was adopted in 1731 by Domingo Lamco (the paternal great-great-grandfather of Jose Rizal), who was a fun-blooded Chinese. Rizal's family acquired a second sur- name — Rizal — which was given by a Spanish alcalde mayor (provincial governor) of Laguna, who was family friend. Thus said Dr. Rizal, in his letter to Blumentritt (without date or place):' I am the only Rizal because at home my parents, my sisters, my brother, and my relatives have always preferred our old surname Mercado. Our family name was in fact Mercado, but there were many Mercados in the Philippines who are not related to us. It is said that an alcalde mayor, Who was a friend of our family added Rizal to our name. My family did not pay much attention to this, but now I have to use it. In this way, it seems that I am an illegitimate "Whoever that Spanish alcalde mayor was," commented Ambassador Leon Ma. Guerrero, distinguished Rizalist and diplomat, "his choice was prophetic for Rizal in Spanish means a field where wheat, cut while still sprouts again. The Rizal Home. Ihe house of the Rizal family, where the hero was tx»rn, was one of the distinguished stone houses in Calamba during Spanish times. It was a two-storey building, rectangular in shape, built of adobe Stones and and roofed with red tiles. It is descritk.d by Dr. Rafael Palma, one of Rizal's prestigious biographers, as follows:9 The house was high and even sumptuous, a solid and massive earthquake-prcx)f Structure With Sliding shell Win- dows. Thick walls Of lime and Stone bounded the first fltxr; the floor was made entirely of wood except for the roof, which was of red tile, in the style of the buildings in Manila at that time . At the back there was an azotea and a wide, deep cistern to hold rain water for home use. Behind the house were the yard full of turkeys and chickens and a big garden of tropical fruit trees — atis, balimbing, Chico, macopa, papya, santol, tampoy, etc. 6 It was a hany home where parental affection and children's laughter reigned. By day, it hummed with the noises of children at play and the songs of the birds in the garden. By night, it echoed with the dulcet notes of family prayers. Such a Wholesome home. naturally, bred a wholesome family. And such a family was the Rizal family. A and Middle-Claß Family. 'Ihe Rizal family t*longed to the principalia, a town in Spanish Philippines. It was one Of the distinguished families in Calamba. By dint Of honest and hard work and frugal living, Rizal's parents were able to live well. From the farms, which were rented from the Dominican Order , they harvested rice, corn, and sugarcane. ney raised pigs, chickens, and turkeys in their backyard. In addition to farming and stockraising, Doia Teodora managed a general goods store and operated a small flour-mill and a home-made ham press. As evidence of their affluence, Rizal's parents were able to build a large stone house which was situated near the town church and to buy another one. They owned a carriage, which was a status symtx»l Of the ilustrados in Spanish Philippines and a private library (the largest in Calamba) which consisted of more than 1 volumes. Ihey sent their children to the colleges in Manila. Combining affluence and culture, hospitality and courtesy, they participated prominently in ali and religious affairs in the community. They were gracious hosts to all visitors and guests — friars, Spanish officials, and Filipino friends — dur- ing the town fiestas and other holidays. Beneath their roof, all guests irrespective of their color, rank, scy:ial position, and economic status, were welcome. Home Life of the Rizals. Rizal family had a simple, contented, and happy life. In consonance with Filipino custom, family ties among the Rizals were intimately close. Don Francisco and Doha Teodora loved their children, but they never SIX)iled them. •niey were strict parents and they trained their children to love Gcxi, to well, to obedient, and to respect people, especially the old folks. Whenever the children, including Jose Rizal, got into mischief, they were given a sound spanking- Evidently , they in the maxim: "Spare the and smil the child..

Scene 9 (7m 17s)

RIZAL: LIFE. WORKS ANO WRITINGS Every day the Rizals and children) heard Mass in tir town church, particularly during Sundays and Christian holi_ days. ney prayed together daily at home — the Angelus at sunset and the Rosary before retiring to bed at night. After the family prayers, all the children kissed the hands of their parents. Life was not, however. all prayers and church seivices for the Rizal children. They were given ample time and freedom tn play by their strict and religious parents. They played merrily in the azolea or in the garden by themselves. The older ones were allowed to play with the children of other families. Chapter 2 Childhood Years in Calamba Jose kizal had many beautiful memories of childhcxxl in his native town. He grew up in a happy home, ruled by parents, bubbling with joy, and sanctified by God's blessings. His natal town of Calamba, so named after a big native jar, was a fitting cra- die for a hero. Its scenic beauties and its industrious, hospitable, and friendly folks impressed him during his years and profoundly affected his mind and character. ne happiest period of Rizal's lifé was spent in this lakeshore town, a worthy prelude to his Hamlet-like tragic manhood Calamba, the Hero's Town. Calamba was an hacienda town which belonged to the Dominican Order , which also owned all the lands aroupd it. It is a picturesque town nestling on a verdant plain covered with irrigated ricefields and sugar-lands. A few kilometers to the south looms the legendary Mount Makiling in somnolent grandeur, and beyond this mountain is the province of Batangas. East of the town is the Laguna de Bay, an inland lake of songs and emerald waters beneath the canopy of azure skies. In the middle of the lake towers the storied island of Talim, and it towards the north is the distant Antipolo, famous mountain shrine of the miraculous Lady of Peace and Voyage. Rizal loved Calamba with all his heart and soul. In 1876, when he was 15 years old and was a student in the Ateneo de Manila, he rememtrred his town. Accordingly, he wrote a Un Recuerdo A Mi Pueblo (In Memory of My Town), as follows: When early childhood's happy days In memory I see once more Along tir lovely verdant shore 9.

Scene 10 (8m 24s)

RIZAL: LIFE. WORKS AND That meets a gently murmuring sea; When I recall the whisper soft Of zephyrs dancing dn my brow With cooling sweetness, even now New luscious life is in me. When I behold the lily white That sways to do the Wind's command, While gently on the sand ne Stormy water rests awhile; When from the flowers there softly breathes A bouquet ravishingly sweet, Out•vxnared the newborn dawn to meet, As on us she begins to smile. With sadness I recall... recall Thy face , in precious infancy, Oh mother, friend most dear to me, Who gave to life a wondrous charm. I yet a village plain, My joy, my family, my Besides the freshly cool lagoon, — The for which my heart beats warm. Ah yes! my footsteps insecure In your dark forests deeply sank; And there by every river's bank I found refreshment and delight; Within that rustic temple prayed With childhocx]'s simple faith unfeigned While cooling breezes, pure, unstained, Would send my heart on rapturous flight. I saw the Maker in the grandeur Of your ancient hoary Ah, never in your refuge could mortal by regret smitten; And while upon your sky of blue I gaze. love nor tenderness Could fail, for here on nature's dress My happiness itself Was Written. Ah. tender childhmd, lovely town. Rich fount Of my felicities , Oh those harmonious melodies Which put to flight all dismal hours. Come back to my heart once more! 10 Come back , gentle hours, I yearn! Come back as the birds return, At the budding Of the flowers! Alas. farewell! Eternal vigil I keep For thy peace, thy bliss, and tranquility, O Genius Of good, so kind! Give me these gifts, with charity. To thee are my fervent vows, — TO thec I ceaw not to sigh These to learn, and I call to the sky To have thy sincerity. Earliest Childhood Memories. 'Ihe first memory of Rizal. in his infancy, was his happy days in the family garden when he was three years old. Because he was a frail, sickly, and undersized child, he was given the tenderest care by his parents. His father built a little nimi cottage in the garden for him to play in the day time. A kind old woman was employed as an aya (nurse maid) to lcx)k after his comfort. At times, he was left alone to muse on the of nature or to play by himself. In his memoirs, he narrated how he, at the age of three, watched from his garden cottage, the culiauan, the maya, the maria capra, the martin, the pipit, and other birds and listened "with wonder and joy" to their twilight songs. Another memory was the daily Angelus prayer. By nightfall, Rizal related, his mother gathered all the children at the house to pray the Angelus. With nostalgic feeling, he also remembered the happy moonlit nights at the azotea after the nightly Rosary. The aya related to the Rizal children (including Jose) many stories atxyut the fairies; tales of buried treasure and trees blcxirning with diamonds, and other fabulous stories. The imaginary tales told by the aya aroused in Rizal an enduring interest in legends and folklore. when he did not like to take his , the aya would threaten him that the asuang, the nun0, the tigbalang, or a terrible trarded turbaned Bombay would come to take him away if he would not eat his supsrr. Another memory of his infancy was the ncrturnal walk in town, especially when there was a aya him for a walk in the mcxmlight by the river , where the trees cast grotesq'E 11.

Scene 11 (9m 30s)

Gadows the bank. Recounting this childhocxi exrrrience in his stu&nt Rizal wrote: "Thus my heart fed on sombre and melancholic thoughts so that even while still a child. I already wan. dered on wings of fantasy in the high regions of the unknown. "2 Hero's Fü•st The Rizal children were bound together by ties of love and companionship. ney were well-bred, for their snrents taught them to love and help one another. Of his sisters , Jose loved most the little Concha (Concerxion). He was a year oldcr than Concha. He played with her and from her he icarned tir of sisterly love. Unfortunately. Concha died of sickness in 1865 when she was only three years old. Jose, who was very fond of her, cried bitterly at losing her. "When I was four years old." he said, "I lost my little sister Concha. and then for the first time I shed tears caused by love and grief... death of little Concha brought him his first A Of a Catholic Clan , bred in a wholegmne atmosphere of Catholicism, and gd Of an intxyn pious spirit, Rizal grew up a Catholic. At the age of three. Ergan to take in the fanily prayers. His mother. who was a devout Catholic. taught him the Catholic When he was five years old , he was able to reul haltingly the Spanish family Bible. He loved to go to church, to pray, to take part in novenas, am] It is said that he was so seriously devout that he was laughingly called Manong Jose by the Her- Her— Tert-eras. Onc of tlr men he esteemed and regrcted in Calamba during his tx:yytuxxj was the scholarly Father Leoncio town He to viit this learned Filipino priest and listen to his stimulating oriniom on current events and sound philou»phy of On June 6, Jose and hisbther left Calamba to go a pilgrimage to Antirx»lo, in order to fulfill n« Ecompny them krcaux she had given birth to It was the first trip of Jose across Laguna de Bay and his first pilgrimage to AntiiX110. He and his father in a casco (barge). He was thrilled. as a typical should. by his first lake voyage. He did not sleep the whole night as the casco sailed towards the Pasig River trcaug he was awed by "the magnificence of the watery expanse and the silence of the night." Writing many years later of this exrxrience, he said: "With what pleasure I saw the sunrise; for the first time I saw how the luminous rays shone. producing a bril- liant effect oil the ruffled surface of the wide lake. After praying at the shrine of the Virgin of Antipolo, Jose and his father went to Manila. It was the first time Jose saw Manila. They visited Satumina. who was then a tx»arding student at La Concordia College in Santa Ana. The Story or the Moth. Of the stories told by Doha Teodora to her favorite son , Jose. hat of the young moth made the profoun- dest impression on him. Speaking of this incident, Rizal wrote: ' One night. all the family. except my mother and myself. went to early. Why. I do not know. but we two remained sitting alone. candles had already put out. They had been blown out in their glotrs by means Of a curved tutr Of tim nat tutr remed to me the finest plaything in the world. was dimly lighted by a single light of CCXOnut oil, In all Filipino 'Kyrnes scrh a light burns through tix niÖt. It out just Ly-break to awaken people by its spluttering. My mother was tc,E2üng me to read in a rea&.r called Friend— (El Amigo de Nihos). Was quite a rare and an Old copy. It had its cover my sister had cleverly maik new fastcrrd a sheet of thick over it with a piece Of ck*h. ni*t my •ith read _ I did tX't understand Spanish and I could read Vith expreuön. Shc tCX'k thc First drawing funny told me to listen and she trgan to read. •t read very well She recite well. tcx). Many times , my corrected my muk 13.

Scene 12 (10m 37s)

RIZAL: LIFE. WORKS to her, full of childish enthusiasm. 1 marvelled at the Ilia-sounding phrags w hl she read so easily stopped me at every breath. perhaps 1 grew tired of listening to sounds that had no meaning for me. Perhaps I lacked self-control. Anyway, 1 paid attention to the reading. 1 was watching the cheerful name. About it, some little moths were circling in playful flights. By chance, tcx', I yawned. My mother soon noticed that I was not interested. She stopped reading. nen she said to me: "l am going to read you a very pretty story. Now pay atten " On hearing the word 'story' I at once opened my eyes Vide. The word •story' promised something new and wonder. ful. I watched my mother While she turned the leaves Of the as if she were I«'king for something. Then I settled down to listen. I was full of curiosity and wonder. I had never even dreamed that there were stories in the Old book which I read without understanding. My mother began to read me the fable Of the young moth and the Old one. She translated it into Tagalog a little at a time. My attention increased from the first sentence. I looked toward the light and fixed my gaze on the moths which were circling around it. story could not have been better timed. My mother reirated the warning Of the old moth. She dwelt upon it and directed it to me. I heard her, buSit is a curious thing that the light seemed to me each time more beautiful, the name more attractive. I really envied the fortune Of the insects. They frolicked joyously in its enchanting splendor that the ones Which had fallen and been drowned in the oil did not catße me any dread. My mother kept on reading and I listened breathlessly. •me fate of the two insects interested me greatly. The name rolled its golden tongue to one side and a moth Which this movement had singed fell into the Oil, fluttered for a time and then became quiet. That became for me a great event. A curi- ous change came over me which I have always noticed in myself whenever anything has stirred my feelings. The name and the moth seemed to go farther away and my mother's words sounded strange and uncanny I did not notice when she en&d the fable. All my atteption was fixed On the face Of the insect. I watåeditwithrtiy€bolesoul. . . Ithaddiedamartyr to its illusiom. In As she me to bed, my rnc*her said: "See that you do not behave like the young moth. Don't disobedient , or you may get burnt as it did. " I do not know whether I answered or ne Story revealed to me things until then unknown. Moths no longer were, for me, insignificant insects. Moths talked; they knew how to warn. ney advised just liked my mother. The light seemed to me more twautiful. It had grown more dazzling and more attractive. I knew why the moths cir- cled the flame. The tragic fate of the youngnoth, which "died a martyr to its illusions," left a deep impress on Rizal's mind. He justified such noble death, asserting that "to sacrifice one's life for it," meaning for an ideal, is "worthwhile." And, like that young moth, he was fated to die as a martyr for a noble ideal. Artistic Talents. Since early childhood Rizal revealed his God-given talent for art. At the age of five, he began to make sketches with his pencil and to mould in clay and wax objects which attracted his fancy. It is said that one day, when Jose was a mere boy in Calamba, a religious banner which was always used during the fiesta was spoiled. Upon the request of the town mayor, he painted in oil col- Ors a new banner that delighted the town folks because it was better than the original one. Jose had the soul of a genuine artist. Rather an introvertchild , with a skinny physique and sad dark eyes, he found great joy look- ing at the blooming flowers , the ripening fruits, the dancing waves of the lake, and the milky clouds in the sky; and listening to the songs of the birds, the chirpings of the cicadas, and the murmurings of the breezes. He loved to ride on a spirited which his father bought for him and take long walks in the meadows and lakeshore with his black dog named Usman. One interesting anecdote about Rizal was the incident about his clay and wax images. One day when he was about six years old his sisters laughed at him for spending so much time making those images rather than participating in their games. He kept silent as they laughed with childish glee. But as they were departing, he told them: " All right laugh at me now ! *yrneday when I die, people will make monuments and images of me!".

Scene 13 (11m 43s)

ANO Aside from his sketchingandseulpturing a God-given gift for literature. Since early boyhood he had scribbled verses on loose sheets of and on the textbooks ofhis sisters. His mother, who was a lover of ture. noticed his inclination and encouraged him to write At the age of eignt, Rizal wrote his first poem in the native petry. language .entitled sa Aki,tg Mga Kabab-ata (To My Fellow Chil. dren), as follows: 6 TO MY FELLOW CHILDREN Whenever pecTIe Of a country truly love •The language which by heav'n they were taught to use That country also surely liberty pursue As thc bird Which so.•rs to freer For language is the final judge and referee Upon the Fople in thc land where it holds sway; In truth our human race resembles in this way Other living beings born in lit%rty. Wh(rver knows not how to love his native tongue Is worg than any beast or evil smelling fish. TO make our language richer ought to our wish The same as any mother loves to feed her ymmg. Tagalog and the Latin language are the same And English and Castilian and the angels• tongue; And God. watchful care o'er all is flung, Has given us His blessing in the SIEech we claim. Our mother tongue, like all the highest that wc know Had alphabet and letters of its very own; But these were — by furious waves were overthrown Like bancas in the Stormy sea, long years ago. This pern reveals Rizal's earliest nationalist sentiment. In verses, he proudly prcwlaimed that a who truly love their native language will surely strive for liberty like "the bird which soars to freer space atx»ve" and that Tagalog is the equal of Latin. English, Spanish, and any other language. Dram. by Rizal. After writing the rxrrn To My Fellow Children, Rizal, who was then eight years old, wrote his first dramatic work which was a Tagalog comedy. It is said that it 16 was staFd in a Calamba festival and was delightfully applau&d by the audience. A gobernadorcillo from Paete. a town in Laguna famous for lanzones and wcxidcarvings, haprwned to witness the comedy and liked it so much that he purchased the manuscript for two and brought it to his home town. It was staged in Paete during its town fiesta. Rizal as Boy Magician. Since early Rizal had t*en interested in magic. With his dexterous hands, he learned various tricks, such as making a coin appear or disappear in his fingers and making a handkerchief vanish in thin air. He entertained his town folks with magic-lantern exhibitions. ms consisted of an ordinary lamp casting its shadow on a white screen. He twisted his supple fingers into fantastic making their enlarged shadows on the screen resemble certain animals and Errsons. He also gained skill in manipulating marionettes (puppet shows). In later years when he attained manhood. he continued his keen predilection for magic. He read many txx»ks on magic and attended the performances of the famous magicians of the world. In Chapter XVII and XVIII of his second novel, El Filibusterismo (Trea"'n), he revealed his wide knowledge of magic. Lakeshore Reveries. During the twilight hours of summer- time Rizal, accompanied by his pet dog, used to meditate at the shore of Laguna de Bay on the sad conditions of his oppreswd people. Years later, he related: 7 I SIXnt many, many hours of my childhexxl down on the shore Of the lake, Laguna de Bay. I was thinking of What was I was dreaming Of what might over on thc Other side Of the waves. Almost every day, in our town, we saw the Guardia Civil lieutenant caning and injur- ing some unarmed and inoffensive villagers. •nue villager's only fault was that while at a distance hc had not taken off his hat and made his alcalde treated thc villagers in the same Way whenever he visited us. We saw no restraint put upon brutality. Acts Of violen•x I asked myself and Other excesses were committed daily . if, in the lands Which lay across the lake. the in this same way. I wondered if there they tortured any countryman With hard and cruel Whirs merely on suspicion..

Scene 14 (12m 50s)

or&r to in Face. would one have to britx tyrants? Ymmg was, grieved &eply over the situation of his trloved fatherland. ne Spanish awakened in his t»yi.sh heart a great determination to fiøt tyranny. When he trcarne a man. many years later, he to his friend. Mariano Ponce: "In view of these injustices and cnrlt:ies, although' yet a child. my imagination was and I made a vow dedicating sonwday to avenge many victims. With this idea in my mind, I studied, and this is sen tn all my writings. Someday Gmi will give me the to fulfill my promise. Hero's On the night Jose Rizal born, other children were tK)rn in Calamba hundreds of other children were also torn all over the Philippines. But why is it that out of all these children, only one t-x»y— JOSE RIZAL — rose to fame and greatness? In the lives of all men there are influences which some to great and others not. In the case of Rizal, he all the favorable innuences, few other children in his enjoyed. nese influences were the following: (1) hereditary influence, (2) environmental influence. and (3) aid of Divirr Providence. l. Hereditary Influence: According to biological science. there are inherent qualities which a inherits from his ancestors and parents. From his Malayan ancestors, Rizal. evi- dently, inherited his love for freedom, his innate desire to travel, and his indomitable courage. From his Chinese ancestors. he derived his serious nature, frugality. and love children. From his Spanish ancestors. he got his elegance of bearing. sensitivity to insult, and gallantry to ladies. From his father. he inherited a profound sense of self-respect, the love for work, and the habit of independent thinking. And from his mother. he inherited his religious nature, the spirit of self-sae ritice. and the passion for arts and literature. 2, Environmental Influence: According to psychologists, environment. as well as heredity, affects the nature of a person. Environmental influence includes places. associates, and events. The swnic trauties of Calamba and the beautiful garden Of the Rizal family stimulated the int»rn artistic and literary talents of Rizal, The religious atmosphere at his home fortified his religious nature. His brother. Paciano, instilled in his mind the love for freedom and justice. From his sisters. he learned to courteous and kind to women. Ihe fairy tales told by his aya during his early awakened his Olterest in folklore and His three urr:les. brotirrs of his mother, exerted a gcxxi influence him. Tio Jose Alberto, who had studied for eleven years in a British schex»l iri Calcutta. India. and had traveled in Eurosx inspired him to develop his artistic ability. Tio Manuel. a husky and athletic man, encouraged him to develop his frail by means of physical exercises. including horu riding. walking. and wrestling. And Tio Gregorio. a lover. inten- his voracious reading of gcu»d bc»ks. Father Leoncio the old and learned parish priest of Calamba, fostered Rizal's love for scholarship and intellectual The sorrows in his family. such as the death of Concha in and the imprisonment of his mother in 1871-74. contributed to strengthen his character, enabling him to resist blows of adversity in later years. The Spanish abuses and cruelties which he in his tx»yhocxl. such as the brutal acts of the lieutenant of the Guardia Civil and the alcalde. the unjust tortures inflicted on inncxent Filipinos, and thc execution of Fathers Gomez. Burgos. and Zamora in 1872, awakened his spirit of patriotism and inspired him to consecrate his life and talents to redeem his oppressed people. 3. Aid of Divine Providence: Greater than heredity and environment in the fate of man is the aid of Divine Provicknce. A vxrson may have everything in life — brains. wealth, and — but. Without the aid Of Divine Providence. he cannot attain greatness in the annals of the nation. Rizal was providen• tially destined to the pride and glory of his nation. Gc.xi had endowed him with the versatile gifts of a genius, thc vibrant spirit of a nationalist, and the valiant heart to sacrifice for a öle eau*. 19.

Scene 15 (13m 56s)

Chapter 3 Early Education in Calamba and Biian Rizal had his early education in Calamba and Binan. It was a typical schooling that a son of an ilusrado family during his time. characterized by the four R •s — reading. Writing, arithmetic, and religion. Instruction was rigid and strict. Know. ledge was forced into the minds of the pupils by means of the tedius memory method aided by the teacher's whip. Despite the defects of the Spanish system of elementary education, Rizal was able to acquire the necessary instruction preparatory for college work in Manila gnd abroad. It may be said that Rizal. who was txyrn a physkal •vakling, rose to become an giant not because of, but rather in spite of, the outmoded and backward system of instruction obtaining in the Philippines during last decades of Spanish regime. Hero's First Teacher. The first teacher Of Rizal was his mother, who was a remarkable woman of good character and fine culture. On her lap, learned at the age of three the alphatkt and the prayers. "My mother," wrote Rizal in his student memoirs, "taught me how to read and to say haltingly the humble prayers which I raised fervently to God. "l As a tutor, Dona Teodora was patient, conscientious: and ur&ßtanding. It was she who first disa»vered that her son had a talent for poetry. she encouraged him to write rxrms. To lighten the monotony of memorizing the ABCs and to stimulate her Mya's imagination, she related many stories. As Jose grew older, his parents employed private tutors to bee him at home. The first was Maestro Celestino and the *cond. Maestro Lucas Padua. Later, an old man Leon Monroy, a former classmate of Rizal's father. became the boy's tutor. This old teacher lived at the Rizal home and instructed in Spanish and Latin. Unfortunately. he did not live long. He died five months later. Atter Monroy's death. the hero's parents decided to gnd their gifted son to a private in Binan. G«.s to Binan. One Sunday afternoon in June, 1869. Jose, after kissing the hands of his parents and a tearful parting from his sisters. left Calamba for Birian. He was accompanied by Paciano, who acted as his second father. The two brothers in a carromata, reaching their destination after one and one-half hours' drive. They proceeded to their aunt's house, where Jose was to lodge. It was almost night when they arrived. and the moon was about to rise. That same night. Jose, with his cousin named Leandro. went sightseeing in the town. Instead of enjoying the sights, Jose became depressed because of homesickness. "In the moonlight," hc recounted, "I remembered my home town, my idolized mother, and my solicitous sisters. Ah, how su•eet to me was Calamba. my own town. in spite of the fact, that it was not as wealthy as Birian.-2 First Day in Binan The next morning (Monday) Paciano brought his younger brother to the school of Maestro Justiniano Aquino Cruz. •me school was in the house of the teacher, which was a small nipa hut about 30 meters from the home of Jose•s aunt. Paciano knew the teacher quite well because he had tren a pupil under him before. He introduced Jose to the teacher. after which he departed to return to Calamba. Immediately, Jose was assigned his seat in the class. teacher asked him: "Do you know Spanish?" "A little, sir," replied the Calmnba lad. "Do you know Latin?" "A little, sir." 21.

Scene 16 (15m 3s)

Tve in the clas, Pedro. the teacher's laughed at Jog's answers. Ihe texher sharply stopped all noise and trgan the ot thc day. Jose dexribed his teacher in Binan as follows: "He tall, thin, long-necked. with a sharp nosc and a txxly slightly t*nt forward. and he used to wear a sinamay shirt. Woven by the skilled hands of the women of Batangas. He knew by heart the grammars by Nebrija and Gainza. Add to this his severity. that in my judgment was exaggerated. and you have a picture Frhr vague. that I have made of him, but remember only: First Brawl. In the afterncx»n of his first day in when the teacher was having his siesta. Jose met the bully. Pedro. He was angry at this bully for making fun of him during his conversation with the texher in the nuyrning. Jose challenged Pedro to a fight. The latter readily accepted. thinking that could easily beat the Calamba boy who smaller and younger. ne two tus wrestled furiously in the much to the glee of their classmates. Jose, hasing learned the art of wrestling from his athletic Pio Manuel. defeated the bigger boy. For this feat. he became popular among his classmates. After the class in the afternoon, a classmate named Andres Salandanan challenged him to an arm-wrestling match. ney went to .a sidewalk of a house and wrestlcd with their arms Jose, having the weaker arm. and nearly cracked his head on the sidewalk. In succeeding days he had other fights with the tx»ys of Binan. He was not quarrelsome by nature. but hc never ran away from a fight. Painting Lessons in Binan. Near the school was the house of an Old painter. called Who was lhe father-in-law of the school teacher. Jose, lured by his love for painting. spent many leisure hours at the painter's studio. Old Juancho freely gave him lessons In drawing and painting. He was impressed by tlr artistic talent ot the Calamba lad 22 and his clasgnate. Guevarra, who also loved painting, became apprentices of the old painter. They improved their art, so that in due time they trcarne —the favorite painters Of the class". Ihily Life in Binan. Jose led a methodical life in Binan, Spartan in simplicity. Such a life contributed much to his future development. It strengthened his body and soul. Scraking of his daily life in Bihan, he recorded in his Here was my life. I heard the four o'clock Mass. if any. or I studied my lesson at that hour and I went to Mass afterwards. I returned home and I went to the orchard to for a mabolo to eat. I breakfast. Which consisted generally Of a dish Of rice and two small fish. and I went to class from '-fich I came out at ten O'clcxk. I went home at once. If there was Leamiro and tu»k ot it to the house of his children (Which I never did at home nor would I ever it). I without saying a word. I ate with them afterwards I studied. I went to sch«XiI at two am' at five. prayed a short while with nice cousins and I returned home. I studied my lesson. I drew a little. I tKX»k my supTkr consisting Of one or two dishes of rice with an ayungin. We pray•ed and if there was a my nieces invited me to play in the Street together With Others. Thank God that I never got sick away from my Stu&nt in In academic studies. Jose beat all Binan boys. He surpassed them all in Spanish, Latin, and ottrt of his older classmates were jealous of his intelleetual sußriority. They wickedly squealed to the teacher whenever Jose had a fight outside the s-€hcx»l. and even told lies to discredit him trfore the teacher's eyes. Consequently the teacher had to punish Jose. Thus Rizal said that "in spite of the reputation had of a gocxl boy, the day was unusual when I was laid out on a and given five or sii blows. of Binan Before the Christmas season in 1870. received a letter from his sister Saturnina. informi4 23.

Scene 18 (16m 16s)

years am] a hatf until Manda A— ot alle.ßd thb Rial m h" stu&nt menum: "Our nottwr was un— away from and by By fneo& we treated as honored guests. later that our sick, far frcm us at age. My nothcr was by Manila. She finally to acquitted and eyes ot her Judges. and even After two a hau 26 Chapter 4 Scholastic Triumphs at Ateneo de Manila (1872-1877) •her of Gan-Bur•Z.a and with tn pri«'n. had yet celebrated NrtMay. was to Manila. He studied in the . a un&r the sucrrvision the •as a bitter rival of Dominican-owned Jun Letran. It was formerly the Escuela Pia a in Manila which was by city government in 1817. When the Jesuits. exFlied the Phil#ncs in returtwd to in were given the management oi thc name was changed to Aeneo Municipal. and the de Manila. ney were splendid &cators. that Ateneo acquired prestige as an excellent Ate.eo. On June 10. 1872 Jose. by Pnuno. went to Manila. He tex»k thc entrance examinatioru on Q.nstian arithmetic, and reading at the College of Juan I-ctran. and passed them. He returned to Calarnl* to stay a few days with his family and to attend the town fiesta. His father. who first wished him to study at Letran. his mind and decided to send him to Ateneo instead. 11tus. uB»n his return to Manila, Jose, again accompanid by Pacino, matriculated at the Ateneo MunicipaV At first. Father Magin Ferrando. who was the college registrar, refusd to admit him for two reasons: (l) he was late Ior registration and (2) he was sickly and undersizedfor his age. Rizal was thea eleven years old. However, the intercession of Manwl.

Scene 20 (17m 27s)

RIZAL: LIFE. WORKS students were playing or gossiping. He paid three cwsos for extra Spanish lessons, it was money well svEnt. In the second half of his first year in the Ateneo, Rizal did not try hard enough to retain his academic supremacy which he held during the first half of the term. This was because he resented some remarks of his professor. He placed second at the end of the year, although all his grades were still *Excellent". Summer Vacation (1873). At the end of the scbl year in March, 1873, Rizal returned to Calamba for summer vacati,h. He did not particularly enjoy his vacation because his mother was in prison. To cheer him up, his sister Neneng (Saturnina) brought him to Tanawan with her. This did not cure•his melan- choly. Without telling his father, he went to Santa Cruz and viGted his mother in prison. He told her of his brilliant grade at the Ateneo. She gladly her favorite son. When the summer vacation ended, Rizal returned to Manila for his second year term in the Ateneo. This time he boarded inside Intramuros at No. 6 Magallanes Street. His landlady was an old widow named Doha Pepay, who had a widowed daughter and four sons. Year in Ateneo (1873-14). Nothing unusual happened to Rizal during his second term in the Ateneo, except that he repented having neglected his studies the previous year simply because he was offended by the teacher's remarks. So, to regain his lost class leadership, he studied harder. Once more he "emperor". .%me of his classmates were new. Among them were three boys from Biian, who had his classmates in the scluX)l of Maestro Justiniano. At the end of the schcx»l year , Rizal excellent grades in all subjects and a gold medal. With such scholastic honors, he triumphantly to Calamba in March, 1874 for the summer vacati(m. Prophecy or Mother's Rizal lost no time in going to Santa Cruz in order to visit his mother in the provincialjail• He cheered up Doria Teodora's lonely heart with news of his At 11872-1021 scholastic triumphs in Ateneo and with funny tales his professors and fellow students. The mother was very happy to know that her favorite child was making such splendid progress in college. In the course of their conversation, Dona Tecxiora told her son of her dream the previous night, Rizal, interpreting the dream, told her that she would released from prison in three month's time. Doia Tecxlora smiled, thinking that her son's prophecy was a mere boyish attempt to console her. But Rizal's prophecy became true. Barely three months passed, and suddenly Dona Teodora was set free. By that time, Rizal was already in Manila attending his classes at the Ateneo. Doia Teodora, happily back in Calamba, was even more proud of her son Jose whom she likened to the youthful Joseph in the Bible in his ability to interpret dreams. Teenage Interet in Reading. It was during the summer vacation in 1874 in Calamba when Rizal began to take interest in reading romantic novels. As a normal teenager, he became interested in love stories and romantic tales. The first favorite novel of Rizal was The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexander Dumas. This thrilling novel made a deep impression on him. His imagination was stirred by the sufferings of Edmond Dantes (the hero) in prison, his siRctacular from the dungeon of Chateau d'If, his finding a buried treasure on the nwky island of Monte Cristo, and his dramatic revenge on his enemies who had wronged him. Rizal read numerous other romantic novels with deep interest. reading habit helped to enrich his fecund mind. As a voracious reader, he read not only fiction, but al*) non-fiction. He persuaded his father to buy him a costly set of Cesar Cantu's historical work entitled Universal History. Accord- ing to Rizal, this valuable work was of great aid in his studies and enabled him to win more prizes in Ateneo. Later Rizal read Travels in the Philippines by Dr. Feodor Jagor, a German scientist-traveler who visited the Philippines in 1859-1"). What impressed him in this tx:ok were (l) Jagor's keen observations of the defects of Spanish colonization and (2) 31.

Scene 21 (18m 34s)

RIZAL: his prophecy that someday Spain would lose Philippines and that America would to her as colonizer. Third Year in Ateneo (1814-75). In June 1874, Rizal returned to the Ateneo for his junior year. Shortly after the opening of classes. his mother arrived and joyously told him that she was released from prison, just as he had predicted during his last visit to her prison cell in Santa Cruz. Laguna, He was happy. of course, to see his mother once more a free woman. However, despite the family happiness, Rizal did not make an excellent showing in his studies as in the previous year. His grades remained excellent in all subjects. but he won only one medal — in Latin. He failed to win the medal in Spanish because his srx)ken Spanish was not fluently sonorous. He was beaten by a Spaniard who, naturally. could SIXak Spanish with fluency and with right accentuation. At the end of the school year (March 1875). Rizal returned to Calamba for the summer vacation. He himself was not impre- ss«i by his scholastic work. Fourth Year in Ateneo (1815-76). After a refreshing and happy summer vacation, Rizal went back to Manila for his fourth year course. On June 16, 1875, he became an interno in the Ateneo. One of his professors this time was Fr. Francisco de Paula Sanchez a great educator and scholar. He inspired the young Rizal to study harder and to write poetry. He became an admirer and friend of the slender Calamba lad, Whose God-given genius he saw and on his part, the highest affection and respect for Father Sanchez, whom he considered his best professor in the Ateneo. In his student memoirs, Rizal wrote of Father Sanchez in glowing terms. showing his affection and gratitude. He described this Jesuit professor as "model of uprightness, earnestness, and love for the advancement of his pupils". Inspired by Father Sanchez, Rizal resumed his studies with and zest. He topped all his classmates in au subjects and won five at the end of the school term. He returned to Calamba for his summer vacation (March 1876) and proudly Offered his five medals and excellent ratings to his parents. He was extremely happy. for he was able to repay his "father somewhat for his sacrifices". Last Year in Ateneo (1876-71). After the summer vacation. Rizal returned to Manila in June 1876 for his last year in the Ateneo. His studies continued to fare well. As a matter-of-fact. he excelled in all subjects. Thc most brilliant Atenean of his time. he was truly "the pride of the Jesuits". Rizal finished his last year at the Ateneo in a blaze of glory. He obtained the highest grades in all subjects — philosophy. physics, biology. chemistry. languages. mineralogy, etc. Graduation With Highest Honors. Rizal graduated at the head of his class. His scholastic records at the Ateneo from 1872 to 1877 were as follows: 1872-1873 Arithmetic Latin I Spanish I Greek J Latin 2 . Spanish 2 Greek 2 Universal Geography 1874-1875 Latin 3 Spanish 3 . Greek 3 Universal History History of Spain and the Philippines Arithmetic & Algebra RIEtoric & Poetry French I Geometry & Trigonomäy 33.

Scene 22 (19m 40s)

RIZAL: WORKS 1816-1871 Philosophy I Mineralogy & Chemistry Philosophy 2 Excellent On Commerwement Day, March 23, 1877, Rizal, who was 16 years old, received from his Alma Mater, Ateneo Municipal the degree of Bachelor of Arts, with highest honors. It was a proud day for his family. But to Rizal. like all graduates. Com. mencement Day was a time of bitter sweetness, a joy mellowed with B'ignancy. The night before graduation, his last night at the college dormitory. he could not sleep. Early the following morning, the day of graduation. he prayed fervently at the college chagxl and "commended my life," as he said. "to the Virgin that when I should step into that world, which inspired me with '0 much terror, she would protect me". Extra-curricular in Ateneo. Rizal, unsurpassed in academic triumphs. was not a mere bookworm. He was active in extra-curricular activities. An inside the he was a campus leader outside. He was an active member, later secretary, of a religious society, the Marian Congregation. He was accepted as merntrr of this gxiality not only becaus of his academic brilliance but al*) because of his devotion to Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, the college patroness. Rizal was also a member of the Academy of Spanish Literature and the Academy of Natural These "academies" were exclusive in the Ateneo, to which only Ateneans who were gifted in literature and sciences could qualify for In his leisure hours. Rizal cultivated his literary talent un&r the guidance of Father Sanchez. Another professor, Father Jose Vilacløra, advised him to stop communing with the Muses and more attentim to more practical studies, such as philosophy and natural sciences. Rizal did not heed his advice. He continued to solicit Father Sanchez's help in improving his poetry. Asi& from writing he devoted his spare time to fine arts. He studied painting under the famous Spanish painter, At Agustin Saez, and sculpture under Romualdo de Jesus, noted Filipino sculpior. art masters honored him with their affec- tion, for he was a talented pupil. Furthermore. Rizal, to devel(V his weak body. engaged in gymnastics and fencing. He thereby continued the physical train- ing he Irgan under his Tio Manuel. W«ks in Ateneo. Rizal impressed his Jesuit pro- fesM»rs in the Ateneo with his artistic skill. One day he carved an image of The Virgin Mary on a piece of batikuling (Philippine with his pocket-knife. The Jesuit fathers were amazed at the beauty and grace of the image. Father Lleonart, impressed by Rizal's sculptural talent, requested him to carve for him an image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Young Rizal complied, and within a few days he presented it to Father Lleonart.6 The old Jesuit was highly pleased and profusely thanked the teenage sculptor. He intended to take the image with him to Spain. but, being an absent-minded professor, he forgot to do so. The Ateneo boarding students placed it on the dcxsr of their dormitory, and therc it remained for many years, reminding all Ateneans of Dr. Rizal. the greatest alumnus of their Alma Mater. This image played a significant part in Rizal's last hours at Fort Santiago. Anecdotes Rizal, the Atenean. One of Rizal's contem- poraries in thc Ateneo was Felix M. Roxas. He related an incident of Rizal's schooldays in the Ateneo which reveals thc hero's resignation to pain and forgiveness. One day many Ate- neans, including Rizal, were studying their lessons at the study. hall. Two Ateneans. Manzano and Lesaca. quarreled and vio- lcntly hurled books at each other. Rizal, who was busy at his desk poring over his lessons. was hit in the face by one of thc thrown books He did not raise a cry of protest. although his wounded face was bleeding. His classmates brought him to the infirmary where he had to undergo medical treatment for several days, After the incident, he continued to attend his classes. feeling neither bitterness nor ranco'• towards the guilty party. Another anecdote on Rizai the Atenean was related by Manuel Xeres Burgos. in whose house Rizal t%jarded before he became an interno in the Ateneo. This anecdote.

Scene 23 (20m 46s)

ot Wanda which ia•ng, Juw. Rizal bc was reuhng to htm 't AEted to uv of &.ring 4. 4..

Scene 24 (20m 57s)

RIZAL2 WMKS , he felicitates his mother on her birthda expressing his filial affection in sonorous verses. It runs as MY FIRST INSPIRATION Why do the scented bowers In fragrant fray Rival each Other's flowers This festive day? Why is sweet melody bruited In the sylvan dale, Harmony sweet and fluted Like the nightingale? Why do the birds sing so In the tender grass, Flitting from bough to bough With the winds that pass? And why does the crystal spring Run among the flowers While lullaby zephyrs sing Like its crystal showers? I we the dawn in the East With beauty endowed. Why gcrs she to a feast In a carmine cloud? Sweet mother, they celebrate Your natal day The rose with her scent innate, The bird With his lay. The murmurous spring this day Without alloy, Murmuring bids you always TO live in joy. While the crystalline murmurs glisten, Hear you the accents strong Struck from my lyre, listen! To my love's first *Ing. 38 At Rizal's Poems Education. Although Rizal was merely a teenager, he had a very high regard for egucation. He believed in the significant role which education plays in the progress and welfare of a nation. Thus he stated in his pern.•l THROUGH EDUCATION OUR MOTHERIAND RECEIVES LIGHT vital breath of prudent Education Instills a virtue Of enchanting power; She lifts the motherland to highest station And endless dazzling glories on her And as the zephyr's gentle cahalation Revives the matrix Of the fragrant flower, So education multiplies her gifts of grace; With prudent hand imparts them to the human race. For her a mortal man Will gladly part With all he has; Will give his calm repose: For her are born all sciences and all arts. That brews Of men with laurel fair enclose. As from the towering mountain's lofty heart. The purest current Of the streamlet flows, so education Without stint or measure gives Security and to lands in which she lives. Where education reigns on lofty seat Youth blossoms forth with vigor and agility; His error subjugates with solid feet, And is exalted by conceptions Of nobility, She breaks the neck of vice and its deceit; Black crime turns pale at Her hostility; The barbarous nations She knows how to tame, From savages create heroic fame. And as the spring doth sustenance bestow On all the plants, on bushes in the mead, Its placid plenty goes to Overflow And endlessly with lavish love to feed banks by which it wanders. gliding slow, Supplying beauteous natures every need. So he who prudent Education doth. prexure The towering heights Of honor. will secure. 39.

Scene 26 (22m 10s)

Shan walk in joy and Toward the everywhere ne fragrant and luxuriant fruits of Virtue. Re5gW During his student days expressed his devotion to his Catholic faith in melcxiious One of the religious he wrote was a brief entitl« A1 MAO Jesus (To the Olild Jesus). It is as follows: 12 TO THE CHILD JESUS HOW. God-Child TO earth in cave forlorn? Does Fortune When Thou art carcely Who mortal keep Woulds't rather than *wereign *epherd Of Thy Sheep? This was written in 1875 when he was 14 years old. Another reliöous which he wrote was A La Virgen Maria (To the Virgin Mary). This is undated, that we do not know exactly when it was written. Probabl , Rizal wrote it after his to the auld Jesus. It runs as follows: TO THE VIRGIN MARY Dear Mary. giving comfort and sweet To all afflicted mortals; thou the spring Whence flows a current of relief. to bring Our soil fertility that does mt ceue; Urx•n thy throne. where thou dest high, Oh, list' with pity as I Weetul grieve And spread thy radiant mantle to receive My voice Which rises swiftly to the sky Placid Mary, thou my mother My Sustenance, my fortitude must And in this fearsome sea my way must Steer. If deprivation comes to buffet me, And if grim death in agony draws near, 0b, me, from anguish set me free. 42 While Rizal was Still a stu&nt at the Ateneo, his favorite teacher. Father Sanchez. requested him to write a drama based on the story ot St. Eustace Martyr. During the sumrner vacation of 1876, he wrote the requested religious drama in mxtic at his home in Calamba and finished it June 2. 1876 Upn c*ning of dazes at the Ateneo in June 1876 — his last aca&mic year at the Jesuit college — he submitted to Father Sanchez the finished manuscript of the drama entitled San Eusec.ü', Manir (St. Eustace, the Martyr). The gcxxl pnest- teactwr read it and felicitated the young Atenean for work well Romance of Shortly after his graduation from the Ateneo. Rizal, who was then years old. his first romance — "that painful experience which comes to nearly all adole«ents" girl was Segunda Katigbak. a pretty fourteen-year old Batanguena from Lipa. In Rizal's own words: "She was rather short, with eyes that were elcxpent and ardent at times and languid at others. rosy-cheeked, with an enchanting and smile that revealed very trautiful teeth, and the air of a sylph; her entire self diffused a mysterious charm. "14 One Sunday Rizal visited his maternal grandmother who lived in Trozo. Manila. He was accompanied by his friend, Mariano Katigbak. His old grandmother was a friend of the Katigbak family of Lipa. When he reached his grandmother's house, he saw other guests. One of whom was an attractive girl, who mysteriously caused his heart to palpitate with strange ecstasy. was the sister of his friend Mariano. and her name was Segunda. His guests, who were mostly college studenB. of his skill in painting. so that they urged him to draw Segunda's 1K)rtrait. He complied reluctantly and made a sketch of her. "From time to time," he reminisced later, "she lc»ked at me, and I blushed," IS Rizal came to know more intimately during his weekly visits to La Concordia College, where his sister Olimsi. was a tx»arding student. Olimpia was a close friend of Segunda. It was amyarent that Rizal and Segunda loved each other. •nwirs.

Scene 27 (23m 16s)

RIZAL: LIFE. WORKS AND was indeed "a love at first sight". But it was hopeless Since the very begining because Segunda was already engaged to be mar. ried to her townmate, Manuel Luz. Rizal, for all his artistic and intellectual prowess, was a shy and timid lover. Segunda had manifested, by insinuation and deeds, her affection for him, but he timidly failed to propose. ne last time they talked to each other was one Thursday in December, 1877 when the Christmas vacation was about to begin. He visited Segunda at La Concordia College to say g.ocu bye because he was going home to Calamba the following day. She, on her part, told him she was also going home one day later. She kept quiet after her brief reply, waiting for him to say something which her heart was clamoring to hear. But Rizal failed to come up to her expectation. He couk only mumble: "Well, good-bye. Anyway — I'll see you when you pas Calamba on your way to Lipa." ne next day Rizal arrived by steamer in his hometown. ; mother did not recognize him at first, due to her failing eyesight. He was saddened to find out about his mother's growing blindness. His sisters gaily welcomed him, teasing him about Segunda, for they knew of his romance through Olimpia. That night he demonstrated his skill in fencing to his family. He had a friendly fencing bout with the best fencer in Calamba and bested him. following day (Saturday) he learned that the steamer carrying Segunda and her family would not anchor at Calamba trcause of the strong winds; it would stop in Birian. He saddled his white horse and waited at the road. A cavalcade of carromatas from Bioan passed by. In one of whom was Segunda smiling and waving her handkerchief at him. He doffed his hat and was tongue-tied to say anything. Her carriage rolled on and yanished in the like "a swift shadow". He returned home, dazed and deq»late, with his first romance "ruined by his own shyneg and reserve". ne first girl, whom he loved with ardent fervor, was to him forever. She returned to Lipa and later married Manuel Luz. He remained in Calamba, a frustrated lover, &rbhing MEta1gic memories of a Icht love. 44 At AWO nree years later, Rizal, recording his first and tragic romance, said: "Ended, at an early hour. my first love! My virgin heart will always mourn the reckless step it took on the flower-decked abyss. My illusions will return, yes, but indifferent, uncertain, ready for the first betrayal on the path of love. "16.

Scene 28 (24m 23s)

Chapter 5 Medical Studies at the University of Santo Tomas (1877-1882) Fortunately, Rizal's tragic first romance, with its bitter dis. illusionment, did not adversely affect his studies in the University of Santo Tomas. After finishing the first year of a course in Philosophy and Letters (1877-78), he transferred to the medical course. During the years of his medical studies in this university which was administered by the Dominicans, rival educators of the Jesuits, he remained loyal to Ateneo, where he continued to participate in extra-curricular activities and where he com. pleted the vocation course in surveying. As a Ihomasian, he won more literary laurels, had other romances with pretty girls, and fought against Spanish students who the brown Filipino students. Mother's to After graduating with the highest honors from the Ateneo, Rizal had to go to the University of Santo Tomas for higher studies. The Bachelor of Arts course during Spanish times was equivalent only to the high schcx»l and junior college courses today. It merely qualified its graduate to enter a university. Both Don Francisa» and Paciano wanted Jose to pursue higher learning in the university But Dona Te«xiora, who knew what happened to Gom-Bur-Za, vigorously omx»sed the idea and told her husband: "Don't send him to Manila again; he knows enough. If he gets to know more, the Spaniards will cut off his head. Don Francisco kept quiet and told Paciano to his younger brother to Manila, despite their mother's tears. 46 At Th. O' smto J'%e Rizal hilmelf,was surprised why his mother, who was a wornan of education and culture. should object to his desire for a university education. Years later he wrote in his journal: "Did my mother Irrhaps have a foretxxiing of what would happen to me? a mother's heart really have a second sight?" Rizal Enters the University. In April 1877, Rizal who Was then nearly 16 years old, matriculated in the University of Santo Tomas, taking the course on Philosophy and Letters. He enrolled in this course for two reasons: (1) his father liked it and (2) he was "still uncertain as to what career to pursue". He had written to Father Pablo Ramon, Rector of the Ateneo, who had been gcxxi to him during his student days in that college, asking for advice on the choice of a career. But the Father Rector was then in Mindanao so that he was unable to advise Rizal. Con- sequently, during his first-year term (1877-78) in the University of Santo Tomas, Rizal studied Cosmology, Metaphysics, The(xl- icy , and History of Philosophy. It was during the following term (1878-79) that Rizal, having rewived the Ateneo Rector's advice to study medicine. took up the medical course, enrolling simultaneously in the preparatory medical course and the regular first year medical course. Another reason why he chose medicine for a career was to be able to cure his mother's growing blindness. Finishes Surveying Course in Ateneo (1818). During his first schcK): term in the University of Santo Tomas (1877-78), Rizal also studied in the Ateneo. He took the course leading to thg title of perito agrimensor surveyor). In those days, it should be remembered, the colleges for boys in Manila offered vOcational courses in agriculture, commerce, and surveying. Rizal, as usual, excelled in all subjects in the mrveying course in the Ateneo. obtaining gold medals in agriculture and topography. At the age of 17, he passed the final examination in the surveying course, but he could not granted the title as surveyor because he. was age. The tide issued to him on Novemtrr 25, 1881. Although Rizal was then a •nwmasian, he frequently visited the Ateneo. It was due not only to his surveying course. but.

Scene 30 (25m 36s)

Board Of , Of Wards. Was imp* by Rizal's pem and gave it the first prize which consisted silver and &orated With a gold Young Rizal was happy to Win the poetry contest. He sincerely crmgatulated by the Jesuits. egrcially his former fessors at the Ateneo, and by his friends and relatives. prize-winning A La Juventud Filipina (To filipino Youth). is an inspiring Of flawless form. In ite Rizal trseeched the youth to rise lethargy, to let their genius fly swifter than the wind and descend Vith art and ricoce to break the chains that have long the spirit of the people. This is as follows:' TO THE FILIPINO YOUTH -Grow. O Tnid Hold high the brow serer. O youth. where now stand. Let the bright sheen Of you seen. Fair hope of my fatherland! Come now, thou genius grand, And bring in*ratim; With thy mighty hand, Swifter than the volation, Raise the eager mind to higher statbn. Come with pleBing light Of art and science to the flight. O untie The chains that heavy lie. Your *rit free to See how in nami* Amid the shadows thrown. Spaniard's holy hand A 'Town's resplendent bark] Proffers to this Iulian Thou, Who now WINJdst On of emprise Softer than ambrosial Tbou, voice divine Rivals 's . And varied ThrouÖ night *nign Frees —tüty Bio. by Wakest thy nind to life; And Of thy Makes! irnmoltal in its strength. And thou , in accents clear Or by magic art Takes' from nature's "ore • To fix Go ta-th. fire Of thy genius to the laurel may To armmd the name, And in 'Wry xciaim, Through wi&r wheres human name. Day. O happy day, Fair thy the Power That in thy way This favor •inning Of Rizal is a in for two reasons: First, it Was the first great pem in Wsh written by a whose m•rit was recognized Spanish literary authorities, and secondy , it expresed for the nati«.alÄic concept that the and not the were the -fair hope of the Fattrrland-. •me c.u.c,u the (1m). Ibe ( the Artistic-Literary Lyceum OFned another literary contest to ctnrm«ate the f.Nrth centennial of the eath Cervntes..

Scene 32 (26m 49s)