Bone Augmentation in Implant Dentistry: A Step-by-Step Guide to Predictable Alveolar Ridge and Sinus Grafting - Michael A. Pikos, Richard J. Miron - (2019) 272 pp., ISBN: 9780867158250 part 2

Scene 1 (0s)

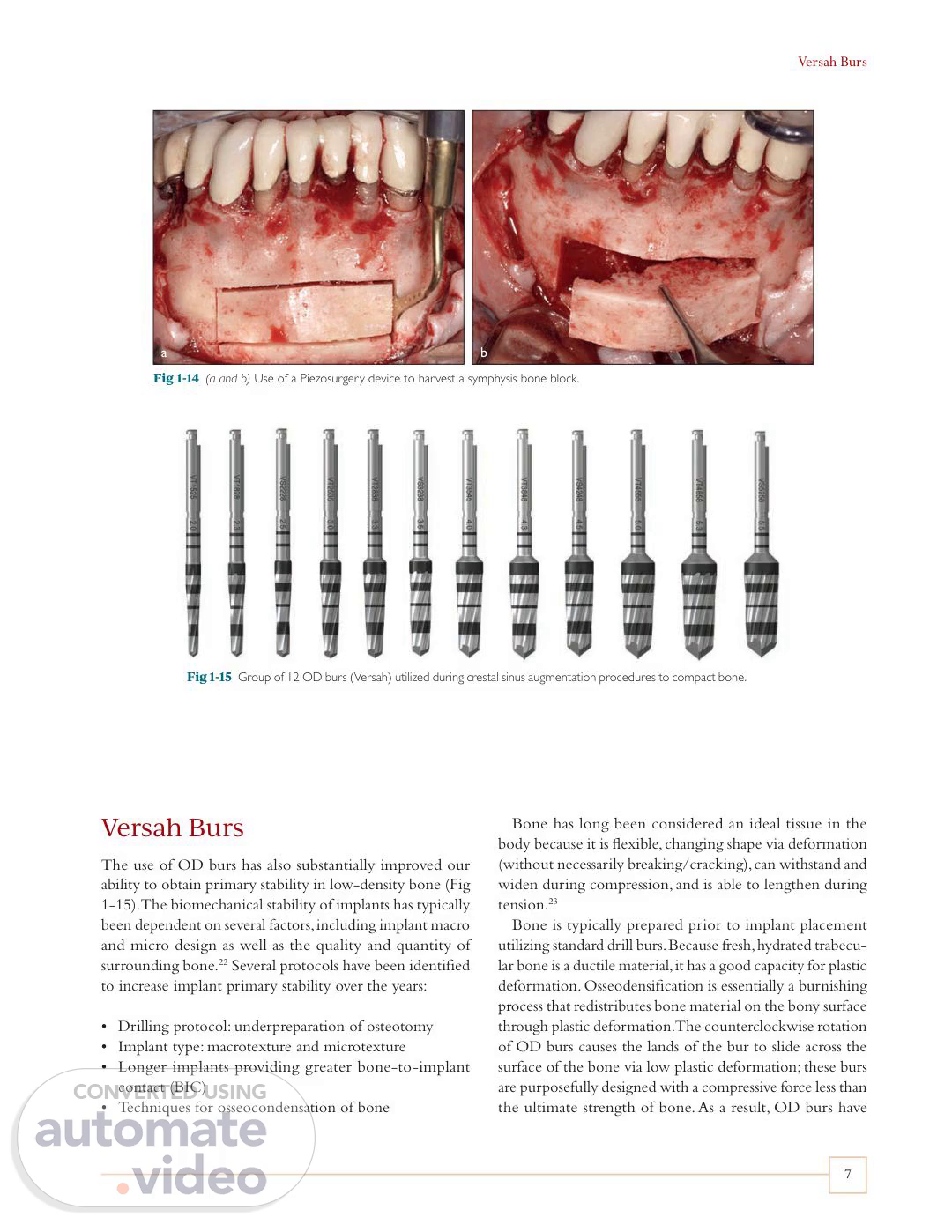

Versah Burs 7 Versah Burs The use of OD burs has also substantially improved our ability to obtain primary stability in low-density bone (Fig 1-15). The biomechanical stability of implants has typically been dependent on several factors, including implant macro and micro design as well as the quality and quantity of surrounding bone.22 Several protocols have been identified to increase implant primary stability over the years: • Drilling protocol: underpreparation of osteotomy • Implant type: macrotexture and microtexture • Longer implants providing greater bone-to-implant contact (BIC) • Techniques for osseocondensation of bone Bone has long been considered an ideal tissue in the body because it is flexible, changing shape via deformation (without necessarily breaking/cracking), can withstand and widen during compression, and is able to lengthen during tension.23 Bone is typically prepared prior to implant placement utilizing standard drill burs. Because fresh, hydrated trabecu- lar bone is a ductile material, it has a good capacity for plastic deformation. Osseodensification is essentially a burnishing process that redistributes bone material on the bony surface through plastic deformation. The counterclockwise rotation of OD burs causes the lands of the bur to slide across the surface of the bone via low plastic deformation; these burs are purposefully designed with a compressive force less than the ultimate strength of bone. As a result, OD burs have Fig 1-14 (a and b) Use of a Piezosurgery device to harvest a symphysis bone block. Fig 1-15 Group of 12 OD burs (Versah) utilized during crestal sinus augmentation procedures to compact bone. b a.

Scene 2 (58s)

[Audio] 1 : Instrumentation for Alveolar Ridge Augmentation and Sinus Grafting SD ED OD a b Fig 1-17 Clinical use of OD burs during a sinus augmentation procedure with minimal residual bone height. c Fig 1-16 Results from a preclinical study demonstrating the capability of OD to densify bone when utilized correctly. (a) Surface view of 5.8-mm standard drilling (SD), extraction drilling (ED), and OD osteotomies. (b and c) Microcomputed tomography midsection and cross section. Notice the layer of dense bone produced on the outer surface of the OD group. (Reprinted with permission from Huwais and Meyer.24) several reported advantages. First, they create live, real-time haptic feedback that informs the surgeon if more or less force is needed, allowing the surgeon to make instantaneous adjustments to the advancing force depending on the given bone density. These burs rotate in a counterclockwise direction and do not "cut" as expected with conventional burs. They therefore densify bone (D3, D4) by rotating in the noncutting direction (counterclockwise at 800–1,200 rotations per minute). It has been recommended by the manufacturer that copious amounts of irrigation fluid be used during this procedure to provide lubrication between the bur and bone surfaces and to eliminate overheating. OD burs have been shown to produce compression waves, where a large negative rake applies outward pressure that laterally compresses bone during the continuously rotating and concurrently advancing bur. This facilitates "compaction autografting" or "osseodensification." During this process, bone debris is redistributed up the flutes and is pressed into the trabecular walls of the osteotomy24 (Fig 1-16). The autografting supplements the basic bone compression, and the condensation effect acts to further densify the inner walls of the osteotomy.25 Trisi et al were one of the first to study the OD technique in an animal model.25 It was found that OD burs increased the percentage of bone density/BIC values around dental implants inserted in low-density bone compared with conventional implant drilling techniques25 (Fig 1-17). These burs are highlighted primarily in chapter 5 under sinus augmentation procedures. 8.

Scene 3 (3m 22s)

[Audio] References Conclusion The use of novel instruments has facilitated the ability of the clinician to perform more predictable and accurate bone augmentation and sinus grafting. Today, the use of CBCT has been shown to markedly improve diagnostics and treatment planning in implant dentistry, and it is something I consider a necessity and standard for the field. In addition to hand instruments that have been utilized and further refined over the years, new instrumentation has become available. This includes but is not limited to radiosurgery, Piezosurgery, Osstell ISQ implant stability devices, and OD burs, all of which can be utilized on a routine basis for alveolar ridge augmentation and sinus grafting in implant dentistry. While their introduction was brief in this chapter, their use is further highlighted in the clinical chapters of this textbook. Furthermore, as the field continues to advance rapidly, new devices will certainly be brought to market in the coming years. For a current list of the tools and instruments utilized for alveolar ridge augmentation in my practice and guidelines for their use, a detailed and up-to-date description is provided at www.pikosonline.com. References 1. Scarfe WC, Angelopoulos C (eds). Maxillofacial Cone Beam Computed Tomography: Principles, Techniques and Clinical Applications. New York: Springer, 2018. 2. Benavides E, Rios HF, Ganz SD, et al. Use of cone beam computed tomography in implant dentistry: The International Congress of Oral Implantologists consensus report. Implant Dent 2012;21:78–86. 3. Ludlow J, Timothy R, Walker C, et al. Effective dose of dental CBCT—A meta analysis of published data and additional data for nine CBCT units. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2014;44:20140197. 4. Urban I, Jovanovic SA, Buser D, Bornstein MM. Partial lateralization of the nasopalatine nerve at the incisive foramen for ridge augmentation in the anterior maxilla prior to placement of dental implants: A retrospective case series evaluating self-reported data and neurosensory testing. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2015;35:169–177. 5. Chan HL, Benavides E, Tsai CY, Wang HL. A titanium mesh and particulate allograft for vertical ridge augmentation in the posterior mandible: A pilot study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2015;35:515–522. 6. Herrero-Climent M, Santos-García R, Jaramillo-Santos R, et al. Assessment of Osstell ISQ's reliability for implant stability measurement: A cross-sectional clinical study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2013;18:e877–e882. 7. Shin SY, Shin SI, Kye SB, et al. The effects of defect type and depth, and measurement direction on the implant stability quotient (ISQ) value. J Oral Implantol 2015;41:652–656. 8. Yoon HG, Heo SJ, Koak JY, Kim SK, Lee SY. Effect of bone quality and implant surgical technique on implant stability quotient (ISQ) value. J Adv Prosthodont 2011;3:10–15. 9. Baldi D, Lombardi T, Colombo J, et al. Correlation between insertion torque and implant stability quotient in tapered implants with knifeedge thread design. Biomed Res Int 2018;2018:7201093. 10. Bruno V, Berti C, Barausse C, et al. Clinical relevance of bone density values from CT.

Scene 4 (7m 39s)

[Audio] chapter 2 MeMbranes, GraftinG Materials, and Growth factors.

Scene 5 (7m 46s)

[Audio] T a b Fig 2-1 The first barrier membranes utilized in dentistry for GTR were cellulose acetate laboratory filter or ePTFE membranes dating back to the 1980s. Demonstrated here are more modern smooth (a) and textured (b) Cytoflex Tefguard (Unicare) ePTFE membranes. he use of biomaterials has played a pivotal role in modern regenerative dentistry. While they were once thought to act as passive structural materials capable of filling bone voids, more recently, a number of regenerative agents with bioactive properties have been brought to market. These materials act to facilitate bone regeneration and have vastly improved the ease and predictability of bone augmentation procedures. This chapter provides an overview of the various biomaterials used for bone regeneration and discusses the regenerative properties of commercially available barrier membranes, bone grafting materials, and growth factors. Each biomaterial is discussed in the context of its biologic properties, and clinical indications are provided with respect to their application in alveolar bone augmentation procedures. Barrier Membranes Guided tissue and bone regeneration were first introduced to the dental field over 20 years ago. Interestingly, in the early 1970s, it was not common knowledge that periodontal ligament cells were responsible for the healing capabilities of bone found in the periodontium.1 From the 1970s until the mid-1980s, it was widely accepted and believed that progenitor cells for all tissues found in the periodontium were located within alveolar bone.2 It was not until the late 1980s, and convincingly at the beginning of the 1990s following a series of experiments in monkeys, that conclusive evidence supported the notion that progenitor cells in the periodontium were derived from the periodontal ligament tissue.3–5 selectively guiding tissue regeneration around tissues in the periodontium. The first barrier membranes utilized were cellulose acetate laboratory filter or expanded polytetrafluoroethylene [ePTFE]) membranes6 (Fig 2-1). Following 3 months of healing, it was concluded by histologic evaluation that the test root surfaces protected from epithelial downgrowth by membranes exhibited considerably more new attachment and bone regrowth.6 The results from this study confirmed the hypothesis that by selectively controlling the proliferation of cells in the periodontium, and by preventing contact with the epithelial and connective tissues, the space-maintaining capability of the membrane would allow for increased regeneration of underlying tissues. Subsequently, the basic principles of guided bone regeneration (GBR) were introduced by providing the cells from bone tissues with the necessary space intended for bone regeneration away from the surrounding connective tissue using a barrier membrane.7 A number of preclinical and clinical studies have since demonstrated that by applying the concepts of GBR, an increase in bone regeneration may be obtained.8–11 While various approaches for increasing new tissue regeneration have been developed, GBR has remained one of the most predictable solutions to bone defect healing. This section presents the advantages and disadvantages of various membranes for GBR procedures, discussing their mechanical properties and degradation rates. Based on these results, it was hypothesized that a higher regenerative potential might be obtained if cells derived from the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone were exclusively allowed to repopulate the root surface away.

Scene 6 (11m 30s)

[Audio] 2 : Membranes, Grafting Materials, and Growth Factors Several commercially available membranes are classified according to their material properties in Table 2-1 and highlighted below.13–38 Space-making Compatibility Mechanical strength Cell occlusivity Degradability timeline Fig 2-2 The ideal barrier membrane for GBR procedures needs to fulfill the following criteria: biocompatibility, space-making ability, cell occlusivity to prevent epithelial tissue downgrowth, ideal mechanical strength, and optimal degradation properties. Nonresorbable membranes Nonresorbable membranes include expanded (ePTFE), high-density (dPTFE), and titanium-reinforced (PTFE-TR) membranes and titanium meshes (Ti mesh).39 A number of animal studies involving various defect configurations as well as histologic data from both animal and human studies have demonstrated higher tissue regeneration with their use.40 Nonresorbable membranes have several advantages and disadvantages. Their main advantage is their superior rigidity over resorbable collagen-based membranes. Their main disadvantage is the requirement for a second surgical intervention to remove the barrier after implantation,41 which bears the potential for re-injuring and/or compromising the obtained regenerated tissue. However, clinical indications presented later in this textbook demonstrate various applications where their use is pivotal because of their superior strength.41 In general, more recent nonresorbable membranes are effectively biocompatible and offer the added ability to maintain sufficient space in the membrane for longer periods when compared to resorbable membranes. They have a more predictable profile during the healing process because of their better mechanical strength, and their handling has been made easier over the years.42 Requirements of barrier membranes for GBR While the first successful barrier membrane was a cellulose acetate laboratory filter by Millipore,12 since then a wide range of new membranes have been designed with better biocompatibility for various clinical applications. Each of these membrane classes possesses distinct advantages and disadvantages. As a medical application in dentistry, barrier membranes should fulfill some fundamental requirements (Fig 2-2): Biocompatibility: The interaction between membranes and host tissue should not induce a foreign body response. Space-making: The ability to maintain a space for cells from surrounding bone tissue for a specific time duration. Cell occlusivity: Prevents fibrous tissue that delays bone formation from invading the defect site. Mechanical strength: Proper physical properties to allow and protect the healing process, including protection of the underlying blood clot. Degradability: Adequate degradation time matching the regeneration rate of bone tissue, avoiding a secondary surgical procedure to remove the membrane. PTFE membranes PTFE membranes were first introduced to dentistry in 1984. Prior to that, these membranes were utilized clinically for similar applications in general medicine as a vascular graft material for hernia repair.43,44 Each side of the porous structure of ePTFE has its own features45: On one side, an open microstructure collar 1 mm thick and with 90% porosity retards the growth of the epithelium during the early wound healing phase; on the other side, a 0.15-mm-thick and 30% porous membrane provides space for new bone growth and acts to prevent fibrous ingrowth. The average healing period after in vivo implantation is approximately 3 to 9 months depending on the clinical application. The advantages of dPTFE membranes (Fig 2-3), which feature 0.2-µm pores, are that they do.

Scene 7 (15m 39s)

[Audio] Barrier Membranes Table 2-1 Classification of different membranes in GBR Type Commercial name (manufacturer) Material Properties Comments GORE-TEX (W. L. Gore) ePTFE Good space maintainer; easy to handle Longest clinical experience13,14 GORE-TEX-TI (W. L. Gore) ePTFE-TR Most stable space maintainer; filler material unnecessary Titanium should not be exposed; commonly used in ridge augmentation15 High-density GORE-TEX (W. L. Gore) dPTFE 0.2-μm pores Avoid a secondary surgery16 Cytoplast (Osteogenics) dPTFE 0.3-μm pores Primary closure unnecessary17 TefGen-FD (Lifecore Biomedical) dPTFE 0.2- to 0.3-μm pores Easy to detach18 Non- resorbable membranes Nonresorbable ACE (ACE Surgical Supply) dPTFE < 0.2-μm pores; 0.2 mm thick Limited cell proliferation19 Titanium Augmentation Micro Mesh (ACE Surgical Supply) Titanium mesh 1,700-µm pores; 0.1 mm thick Ideal long-term survival rate20 Tocksystem Mesh (Tocksystem) Titanium mesh 0.1- to 6.5-µm pore; 0.1 mm thick Minimal resorption and inflammation21 Frios BoneShields (Dentsply Friadent) Titanium mesh 0.03-mm pores; 0.1 mm thick Sufficient bone to regenerate21 M-TAM (Stryker Leibinger) Titanium mesh 1,700-µm pores; 0.1 to 0.3 mm thick Excellent tissue compatibility22 OsseoQuest (W. L. Gore) Hydrolyzable polyester Resorption: 16–24 weeks Good tissue integration23 Biofix (Bioscience) Polyglycolic acid Resorption: 24–48 weeks Good space-making ability24 Well adaptable; resorption: 4–12 weeks Woven membrane; four prefabricated shapes25 Vicryl (Ethicon) Polyglactin 910, polyglycolic- polylactic acid 9:1 Atrisorb (Tolmar) Poly-DL-lactide and solvent Resorption: 36–48 weeks; interesting resorptive characteristics Custom-fabricated membrane "barrier kit"26 Synthetic resorbable membranes EpiGuide (Kensey Nash) Poly-DL-lactic acid Three-layer membrane; resorption: 6–12 weeks Self-supporting; support- developed blood clot27 Resolut (W. L. Gore) Poly(DL-lactide- co-glycolide) Resorption: 10 weeks; good space maintainer Good tissue integration; separate suture material28 VIVOSORB (Polyganics) Poly(DL-lactide- ε-caprolactone) Anti-adhesive barrier; up to 8 weeks' mechanical properties Acts as a nerve guide29 Endoret (BTI Biotechnology); platelet-rich fibrin (PRF process) Patients' own blood Abundant growth factors and proteins mediate cell behaviors; different formulations for various usages; total resorption Enhances osseointegration and initial implant stability; promotes new bone formation; encourages soft tissue recovery30,31 Bio-Gide (Geistlich) Porcine 1 and 3 Resorption: 24 weeks; mechanical strength: 7.5 MPa Usually used in combination with filler materials32 BioMend (Zimmer Biomet) Bovine 1 Resorption: 8 weeks; mechanical strength: 3.5–22.5 MPa Fibrous network; modulates cell activities33 Natural biodegradable materials BioSorb membrane (3M ESPE) Bovine 1 Resorption: 26–38 weeks Tissue integration34 Neomem (Citagenix) Bovine 1 Double-layer product; resorption: 26–38 weeks Used in severe cases35 OsseoGuard (BIOMET 3i) Bovine 1 Resorption: 24–32 weeks Improves the esthetics of the final prosthetics36 OSSIX (OraPharma) Porcine 1 Resorption: 16–24 weeks Increases the woven bone37 ePTFE-TR, titanium-reinforced ePTFE; dPTFE, dense PTFE; M-TAM, micro titanium augmentation mesh. (Reprinted with permission from Miron and Zhang.38) 13.

Scene 8 (16m 44s)

[Audio] 2 : Membranes, Grafting Materials, and Growth Factors Fig 2-3 (a and b) A dPTFE membrane (Cytoplast). a b a b Fig 2-4 Use of a dPTFE membrane for socket grafting. Fig 2-5 A dPTFE membrane reinforced with titanium (Cytoplast Titanium- Reinforced) for improved mechanical strength in single-tooth cases with a facial plate. regrowth (Fig 2-6). The exceptional properties of rigidity, elasticity, stability, and plasticity make Ti mesh an ideal alternative to PTFE products.25,39 Its rigidity provides extensive space maintenance and prevents contour collapse, its elasticity prevents mucosal compression, its stability prevents graft displacement, and its plasticity permits bending, contouring, and adaptation to any unique bony defect (Fig 2-7). The main disadvantage of Ti mesh membranes is increased exposure due to their stiffness. Several reports have demonstrated up to 50% membrane exposure during their use (see chapter 4). Various strategies, including the utilization of leukocyte platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF), are discussed later in this chapter as approaches to minimize membrane exposure. Fig 2-6 Titanium mesh. procedures because they provide additional mechanical strength for the underlying particulate graft complex. Resorbable membranes The advantage of resorbable membranes (Fig 2-8) is that they permit a single-step procedure, thus alleviating patient discomfort and costs from a second procedure and avoiding the risk of additional morbidity and tissue damage. These membranes are more favorable for minor GBR procedures that do not require extensive bone regeneration. Furthermore, they are also utilized extensively during sinus elevation procedures to repair sinus membrane perforations as well as Titanium mesh Titanium-reinforced barrier membranes were introduced as an option for GBR because they provide advanced mechanical support that allows a larger space for bone and tissue 14.

Scene 9 (18m 57s)

[Audio] Barrier Membranes a b Fig 2-7 (a and b) Titanium meshes are adapted according to the defect morphology. Typically two 5-mm Pro-fix screws (Osteogenics) are utilized for both facial and lingual fixation. a b Fig 2-8 (a and b) Type 1 crosslinked bovine collagen membrane (Mem-Lok Pliable, BioHorizons). The prime advantage of collagen membranes is their superior biocompatibility. Fig 2-9 Type 1 crosslinked bovine collagen membrane (Mem-Lok) utilized to cover a lateral window during a sinus augmentation procedure. formation.25 A list of clinically available membranes as well as their resorption times is presented in Table 2-1. to close lateral windows (Fig 2-9). The main disadvantage of resorbable membranes are their varied and sometimes unpredictable resorption rates, which directly affect bone 15.

Scene 10 (19m 56s)

[Audio] 2 : Membranes, Grafting Materials, and Growth Factors a b c d Fig 2-10 SEM analysis of a collagen barrier membrane at three magnifications. (a and b) Membrane surface reveals many collagen fibrils that are intertwined with one another with various diameters and directions (original magnification ×50 and ×200, respectively). (c) High-resolution SEM demonstrating collagen fibrils ranging in diameter from 1 to 5 μm (original magnification ×1,600). (d) Cross-sectional view of a collagen barrier membrane at approximately 300 μm (original magnification ×100). (Reprinted with permission from Miron et al.51) cycle. For these reasons, synthetic resorbable membranes generally cause a higher inflammatory response, and their use has not been widespread in alveolar bone reconstruction procedures. Synthetic resorbable membranes A series of resorbable membranes mainly consisting of polyesters—eg, polyglycolic acid (PGA), polylactic acid (PLA), and poly-ε-caprolactone (PCL)—and their copolymers are also available.46 Aliphatic polyesters, such as polyglycolide or polylactide, are derived from a variety of origins and can be made in large quantities with a wide spectrum, offering different physical, chemical, and mechanical properties. Interestingly, the resorption of various membranes occurs via different pathways. In a review paper on this subject,47 Tatakis et al demonstrated that a large majority of collagen membranes are resorbed by enzymatic activity of infiltrating macrophages and polymorphonuclear leukocytes, while polymers are typically degraded through hydrolysis, and the degradation products are metabolized through the citric acid Membranes based on natural materials The highest number of reported clinical studies involves the use of biodegradable resorbable membranes from natural collagen (see Table 2-1). Membranes based on natural collagen are typically derived from human skin, bovine achilles tendon, or porcine skin and can be characterized by their excellent cell affinity and biocompatibility.48,49 The main drawbacks of these membranes are their potential for losing their space-maintenance ability under physiologic conditions, higher cost, and potential introduction of 16.

Scene 11 (22m 26s)

[Audio] Bone Grafting Materials Mem-Lok Pliable Bio-Gide Fibrous side Not side specific Lower density Smooth side Dense, uniform single layer SEM (cross section) at 50x SEM (cross section) at 50x Fig 2-11 SEM analysis of a dense crosslinked collagen membrane (Mem-Lok) versus a standard membrane (Bio-Gide). the design of current standards and is projected to more favorably promote the success of GBR therapies. Bone Grafting Materials a foreign biomaterial when applying animal-derived collagen.50 Nevertheless, they are by far the most utilized and studied membrane available on the market and offer the advantages of high biocompatibility and biodegradability, eliminating the need for a second surgical procedure. Figure 2-10 shows scanning electron micrographs (SEMs) of a natural non-crosslinked collagen membrane commonly used in GBR procedures,51 while Fig 2-11 compares SEMs of a crosslinked collagen membrane and a standard membrane. Conclusion The use of bone grafting materials in implant dentistry and oral surgery has become so widespread over the past two decades that new products are rapidly brought to market year after year. Each material and category of bone graft has its specific regenerative properties. The most common classification of bone grafting materials includes the following (Fig 2-12): Autografts (same individual) Allografts (human cadaver bones) Xenografts (animal source) Alloplasts (synthetic source) Barrier membranes are pivotal biomaterials for bone augmentation procedures and are greatly utilized throughout the clinical chapters of this textbook. dPTFE membranes have better mechanical properties when compared to resorbable collagen membranes and have been further reinforced with titanium more recently. Similarly, Ti meshes have been increasingly utilized over the years because of their excellent combination of rigidity and stability, which enables them to prevent flap collapse and ensure tension-free bone regeneration. Their drawback, however, is a higher rate of membrane exposure. Resorbable membranes are favored when a second surgical procedure is not needed, preventing secondary complications associated with membrane removal, including additional patient morbidity and potential risk for secondary infection. Collagen membranes are utilized in chapter 5 during sinus elevation procedures for sinus membrane repair and also for lateral window closure. Over the years, each of these classes of barrier membranes has become increasingly more biocompatible. Ongoing research is presently investigating the use of barrier membranes with a variety of additional regenerative agents such as growth factors and antibacterial agents. The next generation of membranes is expected to incorporate more functional biomolecules into This section focuses on the research and regenerative potential of each of these classes of bone grafting materials. Originally bone grafting materials were developed to serve as a passive, structural supporting network, with their main criterion being biocompatibility.52,53 However, advancements in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine have enhanced each of their regenerative capacities, as confirmed by histologic analysis (Fig 2-13). Today many bone grafting materials have specially designed surface topographies at both the micro- and nanoscales aimed to further guide new bone formation once implanted in situ (Fig 2-14). Data from the United States has shown convincingly that allografts are by far the most utilized bone graft currently available on the market (Fig 2-15). Interestingly, only 15% of augmentation procedures utilize autogenous.

Scene 12 (26m 25s)

[Audio] 2 : Membranes, Grafting Materials, and Growth Factors CLASSIFICATION OF BONE GRAFTING MATERIALS Autogenous bone Bone from the same individual Alloplast Material of synthetic origin Allogeneic bone Bone from the same species but another individual Xenogeneic bone Material of biologic origin but from another species Block graft Free frozen bone Material derived from animal bones Calcium phosphates Freeze-dried bone allograft Material derived from corals Glass-ceramics Bone mill Bone scraper Suction device Piezoelectric surgery Material derived from calcifying algae Polymers Demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft Deproteinized bone allograft Material derived from wood Metals Fig 2-12 Classification of bone grafting materials including autografts, allografts, xenografts, and alloplasts. a b c Fig 2-13 (a to c) Core biopsies were harvested prior to implant placement and investigated for new bone formation after grafting with freeze-dried bone allograft (FDBA, MinerOss [BioHorizons]). After 4 months of healing, the nonvital bone was only 5% of the bone mass. 18.

Scene 13 (27m 44s)

[Audio] Bone Grafting Materials a b Synthetic alloplast Xenograft c d Fig 2-14 (a to d) SEMs demonstrating the 3D shape and topography of bone grafting materials. (Reprinted with permission from Miron and Zhang.38) BMP 5% Requires carrier for control Efficacy questionable SYNTHETIC 5% Highly variable properties Slower biodegradation MINERALIZED ALLOGRAFT 37% Can be immunogenic Can carry infection AUTOGRAFT 15% Donor site morbidity Pain, cost, operative risk Limited volume available DEMINERALIZED BONE ALLOGRAFT 16% Can be immunogenic Can carry infection XENOGRAFT 22% Can be immunogenic Can carry infection Fig 2-15 Data regarding the proportional use of each class of bone grafting material in the United States in 2019. The largest percentage of regenerative procedures are performed with allografts (37% mineralized, 16% demineralized), followed by xenografts (22%), autografts (15%), and synthetic grafts/bone morphogenetic protein (5% each). (Reprinted with permission from Miron and Zhang.38) 19.

Scene 14 (29m 1s)

[Audio] 2 : Membranes, Grafting Materials, and Growth Factors transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), as well as to regulate bone formation/resorption.61 A number of comparative studies using autogenous bone alone have been well documented with respect to defect healing.62–65 Autografts remain the gold standard due to their ability to more rapidly stimulate new bone formation when compared to all other classes of bone grafting materials (Fig 2-18).66 The global market for bone grafting materials has now surpassed $2.5 billion dollars annually and is only expected to continue to rise.54 Therefore, a thorough understanding of the regenerative properties of each of these bone grafting materials is necessary; more specifically, clinical guidelines throughout this textbook are presented with rationales for selecting each grafting material for specific clinical indications. Considering the wide range of uses for bone grafting materials, it should be expected that no single material can fulfill the task of augmenting bone in every clinical situation. Furthermore, in many clinical instances, a combination of two or more bone grafting materials is necessary to lead to better and more predictable outcomes. Each grafting material needs to fulfill several properties related to its use, including optimal biocompatibility, safety, ideal surface characteristics, proper geometry and handling, as well as good mechanical properties. Nevertheless, bone grafts are routinely characterized by their osteogenic, osteo- inductive, and osteoconductive properties. The ideal graft should therefore (1) contain osteogenic progenitor cells within the bone grafting scaffold capable of laying new bone matrix, (2) demonstrate osteoinductive potential by recruiting and inducing mesenchymal cells to differentiate into mature bone-forming osteoblasts, and (3) provide an osteoconductive scaffold that facilitates three-dimensional tissue ingrowth.55 Consequently, the gold standard for bone grafting is autogenous bone because it possesses these three important biologic properties.55 Despite its potent ability to improve new bone formation, limitations including extra surgical time and cost as well as limited supply and additional patient morbidity have necessitated alternatives. This section discusses harvesting techniques for autogenous bone with respect to cell survival content, currently utilized bone allografts, the advantages of xenografts, and the current limitations of synthetic alloplasts.56–60 Autogenous bone Autogenous bone grafting involves the harvesting of bone obtained from the same individual and collected either as a bone block or in particulate form (Fig 2-16). Typical harvesting sites in the oral cavity include the mandibular symphysis, ramus buccal shelf, and tuberosity (Fig 2-17). The main advantage of autogenous bone is that it incorporates all three of the primary ideal characteristics of bone grafts (ie, osteoconduction, osteoinduction, and osteogenesis). Autogenous bone grafts are known to release a wide variety of growth factors, including bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), Harvesting techniques: Block graft versus particles Much research over the years has compared the use of block grafts versus particulate grafts. Of critical importance to the success of any autograft procedure is the clinician's ability to successfully harvest bone with vital osteoprogenitor cells. It has previously been demonstrated that autograft.

Scene 15 (32m 52s)

[Audio] Bone Grafting Materials a b Fig 2-16 Autogenous bone can be collected via either (a) a bone block or (b) bone particles. b a c d Fig 2-17 Intraoral autogenous bone harvesting from the (a and b) ramus and (c and d) symphysis. 21.