Scene 1 (0s)

Michael c.f MiKE MULLIN.

Scene 3 (11s)

By Mike Mullin Tanglewood • Terre Haute, IN.

Scene 4 (18s)

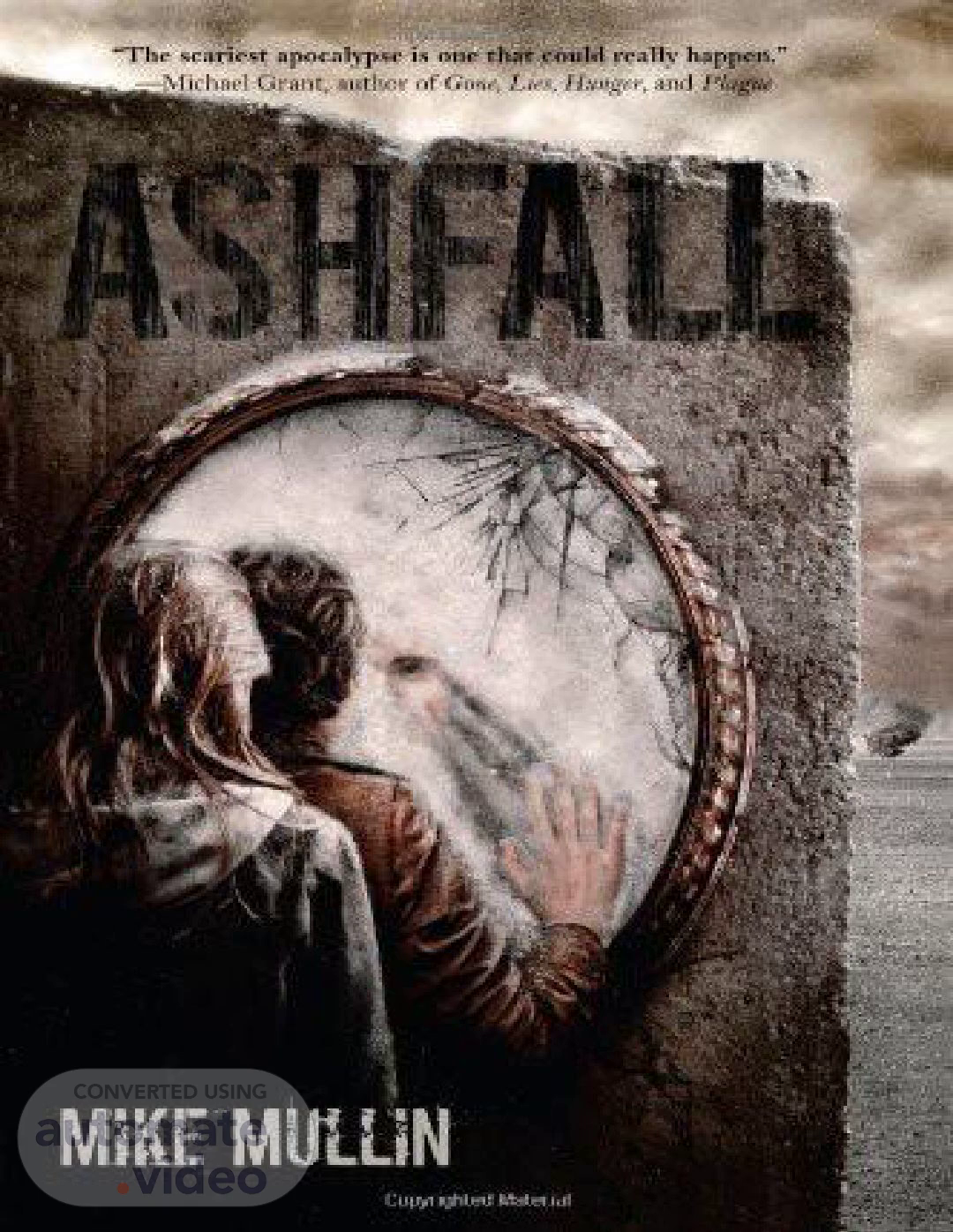

Text © Mike Mullin 2010 All rights reserved. Neither this book nor any part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover photograph by Ana Correal Design by Amy Alick Perich Tanglewood Publishing, Inc. 4400 Hulman Street Terre Haute, IN 47803 www.tanglewoodbooks.com 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN 978-1-933718-55-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mullin, Mike. Ashfall / Mike Mullin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. Summary: After the eruption of the Yellowstone supervolcano destroys his city and its surroundings, fifteen-year-old Alex must journey from Cedar Falls, Iowa, to Illinois to find his parents and sister, trying to survive in a.

Scene 5 (52s)

transformed landscape and a new society in which all the old rules of living have vanished. ISBN 978-1-933718-55-2 [1. Volcanoes--Fiction. 2. Survival--Fiction. 3. Science fiction.] I. Title. PZ7.M9196As 2011 [Fic]--dc22 2011007133.

Scene 6 (1m 7s)

For Margaret, my Darla.

Scene 7 (1m 13s)

Contents Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21.

Scene 8 (1m 23s)

Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Chapter 26 Chapter 27 Chapter 28 Chapter 29 Chapter 30 Chapter 31 Chapter 32 Chapter 33 Chapter 34 Chapter 35 Chapter 36 Chapter 37 Chapter 38 Chapter 39 Chapter 40 Chapter 41 Chapter 42 Chapter 43 Chapter 44 Chapter 45 Chapter 46 Chapter 47.

Scene 9 (1m 33s)

Chapter 48 Chapter 49 Chapter 50 Chapter 51 Chapter 52 Chapter 53 Chapter 54 Chapter 55 Chapter 56 Chapter 57 Chapter 58 Author’s Note Acknowledgments About the Author.

Scene 10 (1m 42s)

Chapter 1 Civilization exists by geological consent, subject to change without notice. —Will Durant I was home alone on that Friday evening. Those who survived know exactly which Friday I mean. Everyone remembers where they were and what they were doing, in the same way my parents remembered 9/11, but more so. Together we lost the old world, slipping from that cocoon of mechanized comfort into the hellish land we inhabit now. The pre-Friday world of school, cell phones, and refrigerators dissolved into this post-Friday world of ash, darkness, and hunger. But that Friday was pretty normal at first. I argued with Mom again after school. That was normal, too; we fought constantly. The topics were legion: my poor study habits, my video games, my underwear on the bathroom floor—whatever. I remember a lot of those arguments. That Friday they only fueled my rage. Now they’re little jewels of memory I hoard, hard and sharp under my skin. Now I’d sell my right arm to a cannibal to argue with Mom again. Our last argument was over Warren, Illinois. My uncle and his family lived there, on a tiny farm near Apple River Canyon State Park. Mom had decided we’d visit their farm that weekend. When she announced this malodorous plan, over dinner on Wednesday, my bratty little sister, Rebecca, almost bounced out of her chair in delight. Dad responded with his usual benign lack of interest, mumbling something like, “Sounds nice, honey.” I said I would not be going, sparking an argument that continued right up until they left without me on that Friday afternoon. The last thing Mom said to me was, “Alex, why do you have to fight me on absolutely everything?” She looked worn and tired standing beside the.

Scene 11 (2m 47s)

minivan door, but then she smiled a little and held out her arms like she wanted a hug. If I’d known I might never get to argue with her again, maybe I would have replied. Maybe I would have hugged her instead of turning away. Cedar Falls, Iowa, wasn’t much, but it might as well have been New York City compared to Warren. Besides, I had my computer, my bike, and my friends in Cedar Falls. My uncle’s farm just had goats. Stinky goats. The males smell as bad as anything short of a skunk, and I’ll take skunk at a distance over goat up close any day. So I was happy to wave goodbye to Mom, Dad, and the brat, but a bit surprised I’d won the argument. I’d been home alone before—I was almost sixteen, after all. But a whole weekend, that was new. It was a little disappointing to be left without some kind of warning, an admonition against wild parties and booze. Mom knew my social life too well, I guess. A couple of geeks and a board game I might manage; a great party with hot girls and beer would have been beyond me, sadly. After I watched my family drive off, I went upstairs. The afternoon sun blazed through my bedroom window, so I yanked the curtains shut. Aside from the bed and dresser, my bedroom held a huge maple bookcase and desk that my dad had built a few years ago. I didn’t have a television, which was another subject Mom and I fought about, but at least I had a good computer. The bookcase was filled with computer games, history books, and sci-fi novels in about equal proportions. Odd reading choices maybe, but I just thought of it as past and future history. I’d decorated my floor with dirty clothes and my walls with posters, but only one thing in the room really mattered to me. In a wood-and-glass case above my desk, I displayed all my taekwondo belts: a rainbow of ten of them starting with white, yellow, and orange and ending in brown, red, and black. I’d been taking classes off and on since I was five. I didn’t work at it until sixth grade, which I remember as the year of the bully. I’m not sure if it was my growth spurt, which stopped at a depressingly average size, or finally getting serious about martial arts, but nobody hassles me anymore. I suppose by now those belts are burnt or buried in ash—most likely both. Anyway, I turned on my computer and stared at the cover of my trigonometry textbook while I waited for the computer to boot up. I used to think that teachers who gave homework on weekends should be forced to grade papers for an eternity in hell. Now that I have a sense of what hell.

Scene 12 (3m 52s)

might be like, I don’t think grading papers forever would be that bad. As soon as Windows started, I pushed the trig book aside and loaded up World of Warcraft. I figured there’d be enough time to do my homework Sunday night. None of my friends were online, so I flew my character to the Storm Peaks to work on daily quests and farm some gold. WoW used to hold my interest the way little else could. The daily quests were just challenging enough to keep my mind occupied, despite the fact that I’d done them dozens of times. Even gold farming, by far the most boring activity, brought the satisfaction of earning coin, making my character more powerful, achieving something. Every now and then I had to remind myself that it was all only ones and zeros in a computer in Los Angeles, or I might have gotten truly addicted. I wonder if anyone will ever play World of Warcraft again. Three hours later and over 1,000 gold richer, I got the first hint that this would not be a normal Friday evening. There was a rumble, almost too low to hear, and the house shook a little. An earthquake, maybe, although we never have earthquakes in Iowa. The power went out. I stood to open the curtains. I thought there might be enough light to read by, at least for a while. Then it happened. I heard a cracking noise, like the sound the hackberry tree in our backyard had made when Dad cut it down last year, but louder: a forest of hackberries, breaking together. The floor tilted, and I fell across the suddenly angled room, arms and legs flailing. I screamed but couldn’t hear myself over the noise: a boom and then a whistling sound—incoming artillery from a war movie, but played in reverse. My back hit the wall on the far side of the room, and the desk slid across the floor toward me. I wrapped myself into a ball, hands over the back of my neck, praying my desk wouldn’t crush me. It rolled, painfully clipped my right shoulder, and came to rest above me, forming a small triangular space between the floor and wall. I heard another crash, and everything shook violently for a second. I’d seen those stupid movies where the hero gets tossed around like a rag doll and then springs up, unhurt and ready to fight off the bad guys. If I were the star in one of those, I suppose I would have jumped up, thrown the desk aside, and leapt to battle whatever malevolent god had struck my.

Scene 13 (4m 57s)

house. I hate to disappoint, but I just lay there, curled in a ball, shaking in pure terror. It was too dark under the desk to see anything beyond my quivering knees. Nor could I hear—the noise of those few violent seconds had left my ears ringing loudly enough to drown out a marching band if one had been passing by. Plaster dust choked the air, and I fought back a sneeze. I lay in that triangular cave for a minute, maybe longer. My body mostly quit shaking, and the ringing in my ears began to fade. I poked my right shoulder gingerly; it felt swollen, and touching it hurt. I could move the arm a little, so I figured it wasn’t broken. I might have lain there longer checking my injuries, but I smelled something burning. That whiff of smoke was enough to transform my sit-here-trembling terror into get-the-hell-out-of-here terror. There was enough room under the desk to unball myself, but I couldn’t stretch out. Ahead I felt a few hollow spaces amidst a pile of loose books. I’d landed wedged against my bookcase. I shoved it experimentally with my good arm—it wasn’t going anywhere. The burning smell intensified. I slapped my left hand against the desk above me and pushed upward. I’d moved that heavy desk around by myself before, no problem. But now, when I really needed to move it, nothing . . . it wouldn’t shift even a fraction of an inch. That left trying to escape in the direction my feet pointed. But I couldn’t straighten my legs—they bumped against something just past the edge of the desk. I planted my feet on the obstacle and pushed. It shifted a little. Encouraged, I stretched my good arm through the shelves, placing my hand against the back of the bookcase. And snatched it away in shock—the wall behind the bookcase was warm. Not hot enough to burn, but warm enough to give me an ugly mental picture of my fate if I couldn’t escape—and soon. I hadn’t felt particularly claustrophobic at first. The violence of being thrown across the room left no time to feel anything but scared. Now, with the air heating up, terror rose from my gut. Trapped. Burned alive. Imagining my future got me hyperventilating. I inhaled a lungful of dust and choked, coughing. Calm down, Alex, I told myself. I took two quick breaths in through my nose and puffed them out through my mouth—recovery breathing, like I’d use after a hard round of sparring in taekwondo. I could do this..

Scene 14 (6m 2s)

I slammed my hand back against the wall, locked my elbow, and shoved with my feet—hard. The obstacle shifted slightly. I bellowed and bore down on it, trying to snap my knees straight. There’s a reason martial artists yell when we break boards—it makes us stronger. Something gave then; I felt it shift and heard the loud thunk of wood striking wood. Debris fell on my ankles—maybe chunks of plaster and insulation from the ceiling. A little kicking freed my legs, stirring up more dry, itchy dust. I forced my way backward into the new hole. There were twelve, maybe sixteen inches of space before I hit something solid again. The air was getting hotter. Sweat trickled sideways off my face. I couldn’t dislodge the blockage, so I bent at the waist, contorting my body around the desk into an L shape. I kept shoving my body backward into the gap between a fallen ceiling joist and my desk, pushing myself upward along the tilted floor. A lurid orange light flickered down into the new space. When I’d wormed my way fully alongside the joist, I jammed my head and shoulders up through the broken ceiling into what used to be the unfinished attic above my room. A wall of heat slammed into me, like opening the oven with my face too close. Long tendrils of flame licked into the attic above my sister’s collapsed bedroom, cat tongues washing the rafters and underside of the roof decking with fire. Smoke billowed up and pooled under the peak of the roof. The front part of the attic had collapsed, joists leaning downward at crazy angles. What little I could see of the back of the attic looked okay. An almost perfectly round hole had been punched in the roof above my sister’s bedroom. I glimpsed a coin of deep blue sky through the flames eating at the edges of the hole. I dragged myself up the steeply angled joists, trying to reach the back of the attic. My palms were slippery with sweat, and my right shoulder screamed in pain. But I got it done, crawling upward with the heat at my back urging me on. The rear of the attic looked normal—aside from the thick smoke and dust. I crawled across the joists, pushing through the loose insulation to reach the boxes of holiday decorations my mother had stored next to the pull-down staircase. I struggled to open the staircase—it was meant to be pulled open with a cord from the hallway below. I crawled onto it to see if my weight would force it down. The springs resisted at first, but then the hatch picked up.

Scene 15 (7m 7s)

speed and popped open with a bang. It was all I could do to hold on and avoid tumbling into the hallway below. It bruised my knees pretty good, too. I flipped the folded segments of the stair open so I could step down to the second floor. Keeping my head low to avoid the worst of the smoke, I scuttled down the hallway to the staircase. This part of the house seemed undamaged. When I reached the first floor, I heard banging and shouting from the backyard. I ran to the back door and glanced through the window. Our neighbor from across the street, Darren, was outside. I twisted the lock and threw the door open. “Thank God,” Darren said. “Are you okay, Alex?” I took a few steps into the yard and stood with my hands on my knees, gulping the fresh air. It tasted sweet after the smoke-drenched dust I’d been breathing. “You look like three-day-old dog crap. You okay?” Darren repeated. I looked down at myself. Three-day-old dog crap was way too kind. Sweat had drenched my T-shirt and jeans, mixing with plaster dust, insulation, and smoke to form a vile gray-white sludge that coated my body. Somewhere along the way, I’d cut my palm without even feeling it. A smear of blood stained the knee of my jeans where my hand had just rested. I glanced around; all the neighbors’ houses seemed fine. Even the back of my house looked okay. Something sounded wrong, though. The ringing in my ears had mostly faded, but it still took a moment to figure it out: It was completely silent. There were no bird or insect noises. Not even crickets. Just then Joe, Darren’s husband, ran up behind him, carrying a three- foot wrecking bar. “Glad to see you’re out. I was going to break the door down.” “Thanks. You guys call the fire department?” “No—” I gave him my best “what the hell?” look and extended both my palms. “We tried—our house phone is dead, not even a dial tone. Cell says ‘no service,’ but that can’t be; it’s usually five bars here.” I thought about that for two, maybe three seconds and took off running..

Scene 16 (8m 12s)

Chapter 2 Darren and Joe yelled something behind me. I ignored them and made tracks as best I could. My bruised knees weren’t helping, neither was my right shoulder. I probably looked kind of funny trying to sprint with my left arm pumping and my right cradled against my side. Still, I made good time toward the fire station. Partway there, I realized I was being stupid. I’d taken off impulsively, needing to do something— anything—instead of jawing with Darren while my house burned down. I should have asked Darren and Joe to drive me or stopped to grab my bike from the garage. But by the time I’d thought through it, I was almost at the fire station. I noticed a couple of weird things along the way. The traffic light I passed was out. That made the run faster—cars were stopping at the intersection and inching ahead, so I could dart through easily. I didn’t see house lights on anywhere; it was early evening and fairly bright outside, but usually there were at least a few lights shining from somewhere. And in the distance to my left, four thin columns of smoke rose against the deep blue sky. A generator growled at the side of the fire station as I ran up. The overhead door was open. I ran through and dodged around the truck. Three guys in fire pants and light blue T-shirts with “Cedar Falls Fire Department” on the back huddled around a radio. A woman dressed the same way sat in the cab of the ladder truck. “Piece of crap equipment purchasing sticks us with,” I heard one of them say as I approached. “Hey kid, we’re—” The guy broke off mid-sentence when he got a good look at me. Then he sniffed. “Burnt chicken on a stick, you’ve been in a fire. Y’ought to be at the hospital.” I was gasping, out of breath from the run. “I’m okay. . .. Neighbors been trying to call . . . ”.

Scene 17 (9m 17s)

“Yeah, piece of junk ain’t working.” The guy holding the radio mike slammed it down. “My house is on fire.” “Where?” “Six blocks away.” I gave him my address. A guy only slightly smaller than the fire truck beside him said, “We’re not supposed to go out without telling dispatch—how we gonna get backup?” “Screw that, Tiny. Kid’s house is on fire. Load it up!” They all grabbed helmets and fire coats off hooks on the wall. In seconds, I was sandwiched between Tiny and another guy in the back of the cab. I could just see the firefighter at the wheel over the mound of equipment separating the two rows of seats. She flicked a switch overhead, starting the sirens blaring, then threw the truck into gear. It roared down the short driveway and narrowly missed a car that failed to stop. I glanced at Tiny once during the drive back to my house. His eyes were scrunched shut, and he was muttering some kind of prayer under his breath. The firefighter at the wheel laughed maniacally as she hurled the huge truck back and forth across the lanes, into oncoming traffic, and even halfway onto a sidewalk once. She swiveled in her seat to look at me, taking her eyes off the road completely. “Anyone else at home, kid?” “No,” I answered, hoping to keep the conversation short. “Any pets?” “No.” The ride couldn’t have lasted more than a minute, but it felt longer. Between the crazy driving and Tiny’s muttered prayer, I wished I’d run back home instead. The truck slammed to a stop in front of my house, and before I could get my stomach settled and even think about moving, the cab was empty. Both doors hung open. I groaned and slid toward the driver’s side. Everything hurt: both knees, my right shoulder, the muscles in my calves and thighs: my eyes stung, my throat felt raw and, to top it all off, my head had started to ache. Two huge steps led down from the cab. I stumbled on the first one and almost fell out of the truck backward. I caught myself on the grab bar mounted to the side of the truck. When I reached the ground, I kept one hand on the bar, holding myself upright..

Scene 18 (10m 23s)

The house was wrecked. It looked like a giant fist had descended from the heavens, punching a round hole in the roof above my sister’s room and collapsing the front of the house. Flames shot into the sky above the hole and licked up the roof. Ugly brown smoke billowed out everywhere. Thank God my sister wasn’t home. If she’d been in her room, she’d be dead now. An hour ago I’d been looking forward to an entire weekend without her. Now I wanted nothing more than to see her again—soon, I hoped. Mom would burn rubber all the way back from my uncle’s place in Illinois as soon as she heard about the fire. It was only a two-hour drive. I gripped the bar on the fire truck more tightly and tried to swallow, but my mouth was parched. The firefighter wrestled a hose toward the front of the house. Tiny hunched over the hydrant across the street, using a huge wrench to connect another hose to it. Darren and Joe were standing in our next-door neighbor’s yard, so I stumbled over to them. From there I could see the side of my house. One of the firefighters opened the dining room window from the inside and smoke surged out. “You okay?” Darren asked. “Not really.” I collapsed into the cool grass and watched my house burn. “We should take you to the hospital.” “No, I’m okay. Can I borrow your cell? Mine’s in there. Melted, I guess.” I wanted, needed, to call Mom. To know she was on her way back and would soon be here taking care of things. Taking care of me. “Still no service on mine, sorry.” “Maybe it’s only our carrier,” Joe said. “I’ll see if anyone else has service.” He walked across the street toward a knot of people who’d gathered there, rubbernecking. I lay back in the grass and closed my eyes. Even from the neighbor’s yard, I felt the heat of the fire washing over my body in waves. I smelled smoke, too, but that might have been from my clothing. A few minutes later, I heard Joe’s voice again. “Nobody’s got cell service. Verizon, Sprint, T-Mobile, AT&T—all down. Nobody’s got power or landlines, either.” I opened my eyes. “I thought landlines weren’t supposed to go down. I mean, when our power’s out, the old house phone still works. Just not the cordless phones.”.

Scene 19 (11m 28s)

“That’s the way it’s supposed to be. But nobody’s telephones work.” “Huh.” “You know what happened to your house? Looks like something fell on the roof.” “I dunno. Power went out, and then wham, the whole house fell on me.” “Meteor, you think? Or a piece of an airplane, maybe?” “Would that make the power and phones go down?” “No . . . shouldn’t.” “And there are other fires. At least four, judging by the smoke.” Joe peered at the sky. “Yeah. Looks like they’re a ways off. In Waterloo, maybe.” I tried to sit up. The motion triggered a coughing spasm—dry, hacking coughs, every one of them setting off a sharp pain in my head. By the time my coughing fit passed, the headache was threatening to blow off the top of my head. “You want some water?” Joe asked. “Yeah,” I wheezed. “We should take you to the hospital,” Darren said again, as Joe trotted back across the street toward their house. I closed my eyes again, which helped the headache some. The water Joe brought me helped more. I chugged the first bottle and sipped the second. Joe left again—said he was going to find batteries for their radio. Darren stood beside me, and we watched the firefighters work. They’d strung two hoses through a window at the side of the house. All four of the firefighters were inside now, doing who-knew-what. The hoses twitched and jumped as water blasted through them. Pretty soon the flames shooting out the roof died down. I heard sizzling noises, and the smoke pouring out the windows turned from an angry brown to white as the fire surrendered. Two firefighters climbed out a window. One jogged to the truck and got two long, T-shaped metal pry-bars. The other guy walked over to me. “Are you okay? Having any trouble breathing?” he asked. “I’m okay.” “Good. Look, normally we’d call a paramedic and the Red Cross truck to get you some help, but we can’t even raise dispatch. You got anyone you can stay with?”.

Scene 20 (12m 33s)

“He can stay with us,” Darren said. “Till we can get hold of his family, anyway.” “That okay with you, kid?” “Yeah, fine.” I’d have preferred to see Mom’s minivan roaring up the street, but Joe and Darren were okay. They’d lived across the street from us forever. “The fire’s pretty much dead. We’re going to aerate some walls and do a little salvage work. Make sure you stay out of the house—it’s not stable.” “Okay. What started it?” “I don’t know. Dispatch will send an investigator out when we reach them.” “Thanks.” I wished he knew more about what was happening, but it didn’t seem polite to say so. “Come on,” Darren said. “Let’s get you cleaned up.” I struggled to my feet and plodded across the street alongside Darren. The sun had gone down; there was a hint of orange in the west, but otherwise the sky was a gloomy gray. No lights had come on. About halfway across Darren’s yard, I stopped and stared at the white steam still spewing from my partly collapsed home. I put my hands on my knees and looked at the grass. A numb exhaustion had seeped into every pore of my body, turning my muscles liquid, attacking my bones with random aches. I felt like I’d been sparring with a guy twice my size for an hour. Darren rested his hand on my shoulder. “It’ll be all right, Alex. The phones will probably be back up tomorrow, and we’ll get your folks and the insurance company on the line. A year from now, the house will be as good as new, and you’ll be cracking jokes about this.” I nodded wearily and straightened up, Darren’s hand still a comfortable weight on my shoulder. Then the explosions started..

Scene 21 (13m 38s)

Chapter 3 The sound hit me physically, like an unexpected gust of wind trying to throw me off my feet. Two windows in the house next door bowed inward under the pressure and shattered. Darren stumbled from the force, and I caught him with my left hand. I used to watch lightning storms with my sister. We’d see the lightning and start counting: one Mississippi, two Mississippi . . . If we got to five, the lightning was a mile away. Ten, two miles. This noise was like when we’d see the lightning, count one—and wham, the thunder would roll over us-the kind of thunder that would make my sister run inside screaming. But unlike thunder, this didn’t stop. It went on and on, machine-gun style, as if Zeus had loaded his bolts into an M60 with an inexhaustible ammo crate. But there was no lightning, only thunder. I glanced around. The firefighters were running for their truck and the knot of rubberneckers had scattered. The sky was clear. I could barely make out a couple of columns of smoke in the distance, but those had been there for more than an hour. Nothing obvious was wrong except for the godawful noise. My hands were clamped over my ears. I had no memory of putting them there. The ground thumped against the soles of my sneakers. Darren grabbed my elbow, and we ran for his front door. Inside, the noise was only slightly less horrendous. The oak floor in Darren’s entryway trembled under my feet. A fine waterfall of white plaster dust rained from a crack in the ceiling. Joe ran up carrying two stereo headsets and a roll of toilet paper. A third headset was clamped over his ears. He pantomimed tearing off bits of toilet paper and stuffing them in his ears. Quick thinking, that. Joe was definitely the brains of the couple. I jammed a wad of toilet paper into each ear and slapped a headset on. The thunderous noise faded to an almost tolerable roar. But I heard a new sound: my ears ringing, like that annoying high-pitched whine a defibrillator makes when a patient is flatlining on TV..

Scene 22 (14m 43s)

We probably looked silly, standing there with the black cords dangling from the headsets, but nobody was laughing. I shouted at Joe, “Should we go to the basement?” But I couldn’t even hear myself talking over the noise. Joe’s lips moved, but I had no idea what he was saying. Darren was shouting something, too, but the noise of the explosions drowned out all of us. Joe grabbed me and Darren and towed us toward the back of the house. We ran through their master bedroom—it was the fanciest bedroom I’d ever seen, but with the auditory assault we were enduring, I wasn’t about to stop and gawk. The master bathroom was equally impressive, at least what I could see of it by the dim light filtering in from the bedroom. Pink marble floor, huge Jacuzzi tub, walk-in shower, bidet—the works. But best of all, it was an interior room, placed right in the center of the first floor. So it was quiet, sort of. When Joe closed the door, the noise diminished appreciably. Of course, that plunged us into total darkness. Joe reopened the door long enough to dig a D-cell Maglite from under one of the sinks. I held my hands out at my sides and screamed, “Now what?” but I don’t think they could hear me. I couldn’t hear myself. Joe yelled something and pointed the flashlight at the tub. Darren and I didn’t respond, so after a moment Joe stepped into the tub, knelt, and covered the back of his neck with his hands. That made sense. The tub itself was plastic, but it was set into a heavy marble platform. If the house fell, it might protect us. Maybe we’d be better off outside, in the open, but the explosive noise was barely tolerable even now, in an interior room. Joe stood up, and I stepped into the tub beside him. Joe shined the flashlight on Darren’s face. It was red and he was shouting—I saw his mouth working, but his eyes were wide and unfocused. His arms windmilled in wild gestures. Joe stepped out of the tub and hugged him, almost getting clocked by one of his fists in the process. Darren tried to pull away, but Joe held tighter, stroking Darren’s back with one hand, trying to calm him. The beam from the flashlight lurched around the room as Joe moved, giving the whole scene a surreal, herky-jerky quality. He coaxed Darren into the tub, and all three of us knelt. It was a big Jacuzzi, maybe twice the size of the shower/tub combo I was used to, but we were still packed tightly.

Scene 23 (15m 48s)

in there. I put my head down on my knees and laced my fingers over the back of my neck. Someone’s elbow was digging into my side. Then, we waited. Waited for the noise to end. Waited for the house to fall on our heads. Waited for something, anything, to change. My thoughts roiled. What was causing the horrendous noise? Would Joe’s house collapse like mine had? For that matter, what had hit my house? I couldn’t answer any of the questions, but that didn’t keep me from returning to them over and over again, like poking a sore tooth with my tongue. I wasn’t a religious guy. Mom was into that stuff, but I had won that fight two years ago. Except for Christmas and Easter, I hadn’t been inside St. John’s Lutheran since my confirmation. Before then, I had gone pretty much every Sunday, sometimes voluntarily. When I was eleven or twelve, we had this real old guy as a Sunday school teacher. Mom said he’d been in some war: Iraq, Vietnam . . . I forget. Anyway, almost every class he’d say, “There are no atheists in foxholes, kids.” At the time, it was just weird. What did we know about either atheists or foxholes? Nothing. But I sort of understood it now. So I prayed. Nobody could hear me over the noise—I couldn’t even hear myself—but I guess it didn’t matter. It was probably better that Joe and Darren couldn’t hear me, because it didn’t come out too well. “Dear God, please keep my little sister safe. I don’t know what these explosions are, but don’t let them hurt my family. They’re probably in Warren, but I guess you know for sure. I swear I’ll do whatever the hell you want. Go to St. John’s every Sunday, try to be nice to my mother, whatever. Do what you want to me. Just please keep Rebecca, Mom, and Dad—” Thinking about my family got me crying. I hoped prayer counted without the amen and all at the end. I was pretty sure it did. I don’t know how long I knelt at the bottom of that tub. Long enough for my tears to dry and my neck to cramp. I stretched out, kicking someone. Joe lifted the flashlight, and by its light we rearranged ourselves so we were lying in the tub instead of kneeling. We were still packed in there way too tightly. Someone’s knee dug into my thigh. I tried to rearrange myself but just got an elbow in my shoulder instead..

Scene 24 (16m 53s)

Then we waited some more. Two hours? Three? I had no way of knowing. The noise didn’t abate at all. What could make a noise that loud for that long? Thinking about it made me feel small and very, very scared. The smell of fear filled my nostrils—a rancid combination of smoke and stale sweat. The flashlight started to dim, and Joe shut it off—to save the batteries, I figured. Sometime later, someone kicked me in the chest. Then I felt a shoe on top of my hand and jerked it away quickly to avoid getting stepped on. Joe snapped on the flashlight. Darren was standing up, feeling for the edge of the tub. He stepped out gingerly. Joe shrugged and followed him. I got out of the tub, too. The sweaty plaster dust from my house had dried on my arms and face, making me itch. I twisted the handle on one of the sinks. The water came on, which surprised me. Nothing else was working; why should that have been any different? I washed my arms and face as best I could in the darkness. I realized I was thirsty again and gulped water from my cupped hands. While I was cleaning up, Joe had left the room. Darren was sitting on the edge of the tub, staring at his hands folded in his lap. Now Joe returned, carrying an armload of pillows, blankets, and comforters. He spread a comforter in the bottom of the Jacuzzi, added a pillow and a folded blanket, and gestured with the Maglite for me to get back in. I pulled off my filthy sneakers. I climbed into the Jacuzzi and lay down, fully dressed. I felt bad about dirtying their comforter with my nasty clothes, but who knew what might happen later. If something else bizarre went down and I had to run, I sure didn’t want to do it butt naked. I lay on my left side in the Jacuzzi, one pillow under my head, the other clamped on top over the headphones and the toilet paper. The headphones dug into my temples, but that was a minor annoyance. I could still hear both the explosions outside and the ringing in my ears. It’s hard to fall asleep when Zeus is machine-gunning thunder at you. It’s hard to stay awake after an evening spent surviving a house fire. It took a couple more hours, but eventually sleep won, and I drifted off despite the ungodly noise and vibration. Everything would be better tomorrow. I thought: a new day, a new dawn would have to be better than this. I was wrong. There was no dawn the next day..

Scene 25 (17m 58s)

Chapter 4 I woke up and groaned. Everything hurt. My back ached from lying curled in the tub. My right shoulder had frozen up overnight. The muscles in my legs and bruises on my knees screamed with pain. My head throbbed, and my mouth tasted of ash and fungus. I rolled onto my back, throwing the pillow off the top of my head. Losing the pillow was like turning up the volume on the radio four notches—if the radio happened to be playing a thrash band with five drummers. That damn noise. It was still every bit as loud as it had been the night before. I checked the toilet paper in my ears, making sure it was still securely jammed in. The headset had dislodged when I rolled over, so I put it back on, which helped a little. I had no idea what time it was, but I felt like I’d slept for six, maybe eight hours. So the explosions, thunder, or whatever they were had gone on at least that long? What could make a noise like that? Everything I could think of—bombs, thunder, sonic booms—would have ended hours ago. It was warm in the bathroom, but my hands and feet still felt cold and numb. I stayed in the bottom of the tub for a while, trembling and trying to get my breathing under control. But lying around in the bottom of a Jacuzzi wasn’t going to answer any of my questions. I pushed myself out of the tub and fumbled in the darkness for my shoes. Putting on shoes one-handed in darkness so complete that I couldn’t see the laces or my hands was a bit of a trick. I gave up on tying them—my right arm wouldn’t cooperate with the left. I jammed the laces down into the shoes so I wouldn’t trip. I needed to take a leak. But Darren and Joe had sacked out between me and the toilet last night. I had no idea if they were still there, and I really didn’t want to kick them in the dark. After all, I was a houseguest. Sort of a weird houseguest—a fire refugee, sleeping in their bathtub—but still. I figured I could hold it for a while..

Scene 26 (19m 4s)

I had a general memory of where the door was—a few steps diagonally from the head of the bathtub. I stretched out my left arm and shuffled in that direction. Of course I found it by jamming my middle finger painfully against the knob. I slipped into the master bedroom and closed the door behind me. Blackness. It was so dark I couldn’t see my hand held in front of my face. I’d expected the bathroom to be dark since it was an interior room. But last night I’d been able to see fine in the bedroom—the three huge windows let in plenty of light. Even if it was still nighttime, I should have been able to see something. The darkest overcast night I’d ever been in hadn’t been this black. I’d been in darkness like this only once before. About five years ago, Dad took me and my sister into a cave on some land one of his friends owned. Mom flatly refused to go. I didn’t like the narrow entrance or the tight crawlways that followed, but I endured it without complaining; I couldn’t let my sister show me up, after all. I even got through the belly crawl okay, pulling myself along by my fingers, trying not to think about the tons of rock pressed against my back. We stopped in a small but pleasant room at the back of the cave to eat lunch. After we finished, Dad suggested we turn out all our lights to see what total darkness was like. I couldn’t see anything, not even my fingers in front of my eyeballs. As we sat there, it got more and more claustrophobic, like a cold, black blanket wrapped around my face, smothering me. I grabbed for my flashlight, only to feel it slip from my sweating hands and clatter to the cave floor. I groped for it but couldn’t find it. Next thing I knew, I was screaming in my high-pitched, ten-year-old voice, “Turn it on! Turn on the light! Turn it on!” Now, the darkness was exactly like the cold black blanket that had smothered me at the back of the cave. I stifled a sudden urge to yell, “Turn it on!” The only flashlight was back in the bathroom with Joe and Darren. And Dad was over a hundred miles away. I stumbled forward, found the bed by banging my shin into the metal bed frame, and sat down. Putting a dirty butt-print on the bed probably wasn’t the nicest thing to do, but it couldn’t be helped. The world had tilted under me—I had to sit down or fall down, and I had enough bruises already..

Scene 27 (20m 9s)

The gears in my brain ground over the possibilities, trying yet again to make sense of what was happening. Nuclear strike? Asteroids? The mother of all storms? Nothing could account for everything that had happened: the thunderous noise, the flaming hole punched in the roof of my house, the dead phones, this uncanny darkness. A beam of light shining from the bathroom cut through the room. Darren appeared in the doorway; I could see his face in the backwash from the flashlight. The light poked around the bedroom a bit and came to rest on me. Darren said something. I couldn’t hear him over the noise, but I could sort of see his lips. Maybe, “Are you okay?” I shrugged in response. Then I stood up and pantomimed taking the flashlight and going to the bathroom. Darren nodded and handed it over. As I walked into the bathroom, Joe passed me on his way out. I used the toilet and washed my hands at the closer of the two sinks. The water still worked, but the pressure seemed to have dropped since yesterday. Back in the master bedroom, I handed the flashlight to Darren and mouthed “Thanks” at him. He and Joe walked to a window on the other side of the room and pointed the flashlight at the glass. The beam died not far outside, snuffed out by a thick rain of light gray dust falling slowly, in a dense sheet that blacked out all light. Little drifts of dust clung to the muntins dividing the window panes. I tapped the glass, and a bunch of the stuff sloughed off and drifted down, joining the main flow raining down unceasingly. Darren took two steps backward and collapsed onto the bed. The flashlight in his hand trembled as he sat there, staring at his feet. Joe sat beside him and put an arm around his shoulder. I could see Darren’s shoulders shaking—the cord dangling from his headphones wavered—so I turned away to give them some privacy. I stared out the window, trying to figure out what the falling stuff was. It was light gray, like ash from an old fire, but a lot finer—sort of like that powder for athlete’s foot. I leaned closer to the window, trying to get a better look. What I got instead was a smell—the stench of rotten eggs. Someone tapped my shoulder. I turned, and Joe gestured for me to follow. The three of us trooped out of the room using the flashlight to find.

Scene 28 (21m 14s)

our way. When we got to the entryway, Darren shined the flashlight on the front door. It was closed and presumably locked, but a two-inch drift of ash had blown under it. I reached down and touched the stuff—nothing happened, so I picked some up between two fingers. It was fine and powdery but also gritty and sharp, like powdered sugar but with the texture of sand. Slicker than sand, though. It reeked with the same sulfur smell I’d noticed at the window. Joe was wearing a wristwatch. I held out my own wrist and tapped it. He nodded and pushed a button on the side of the watch, lighting the display. It read 9:47. Joe led us into the kitchen and passed out Pop-Tarts for breakfast. We had no way to toast them, of course, but I was so hungry it didn’t matter. He pulled a half-full gallon of milk from the dark fridge. The milk was still cool, even after a night without power. We drank most of it. The flashlight dimmed further while we were eating breakfast. Joe used it to retrieve a candle and matches from a kitchen drawer along with a pad of scratch paper and a pen. He carried everything back to the table. While Joe lit the candle and shut off the flashlight, I snatched the pen and scribbled, “What’s happening?” Joe read my note and added his own below it. “Volcano. The big one. Yesterday, while you guys were watching the fire, I heard about it on the radio.” Joe passed the tablet around. I had to hold the note near the candle and hunch over to read it. Darren took the tablet and wrote, “So that stuff outside is ash? From the volcano?” I wrote, “Volcano? In Iowa?” “No. The supervolcano at Yellowstone,” Joe wrote back. “But that’s what—one thousand miles from here?” Darren wrote. Joe took the tablet back and wrote for a long time. Darren tried to pull it away once, but Joe swatted his hand. “About nine hundred. The volcano had already gone off yesterday when Alex’s house was burning. You remember the big earthquake in Wyoming a few weeks ago? The radio said that was either a precursor or trigger for the eruption. The little tremor we felt yesterday was the start of the explosion. I don’t know what hit Alex’s house. My guess is that it was a chunk of rock blasted off the eruption at supersonic speed. Then about an hour and a half later, the sound of the.

Scene 29 (22m 19s)

explosion finally got here. The ash would be carried our way on the jet stream and take eight or nine hours to arrive.” “Should we go check on the neighbors?” Darren wrote. “Radio said to stay indoors during the ashfall. If you have to go out, you’re supposed to cover your mouth and nose.” “What about my family?” I scrawled. “They’re in Warren with your uncle, right?” Joe wrote. “Supposed to be. How’d you know?” “Your mother told us you’d be home alone this weekend,” Joe wrote. “She asked us to keep an eye out for you.” Typical Mom. Of course she’d figure out a way to spy on me—although now I was happy she had. “Warren is 140 miles east of here, even farther from Yellowstone. It could be better there, right?” “Yes,” Joe wrote. “There will be less noise and ash the farther you are from the volcano. There could be a heavy ashfall here but almost none in Warren.” I hoped Joe was right. I hoped my family was in Warren. They should have made it—they’d left three hours before everything had started. I didn’t remember them talking about stopping for dinner on the way, but I couldn’t really know. “How long is this noise going to last?” Darren jotted. “The news didn’t even warn it was on the way, let alone say how long it would last.” “What about the darkness?” “Anything from a few days to a couple weeks. They didn’t know exactly how big the eruption was.” We traded notes for another hour or so, rehashing the same information. Joe had already told us pretty much everything he knew. We’d burned more than half the candle and completely filled the scratch pad by then. Joe wrote, “I’m going to blow out the candle, to save it. Relight it if you need anything.” The next few hours were, well, how to describe it? Ask someone to lock you in a box with no light, nobody to talk to, and then have them beat on it with a tree limb to make a hideous booming sound. Do that for hours, and if you’re still not bat-shit crazy, you’ll know how we felt. Before that day, I had no idea that it was possible to be insane with both terror and boredom at.

Scene 30 (23m 24s)

the same time. I’m not normally a touchy-feely kind of guy, but the three of us held hands most of that time. Lunch was a huge relief, if only because it gave us something different to do. Joe squeezed my hand once and let go. I saw a couple little flashes of light, him using the light of his watch to find stuff. A few minutes later he was back, pressing food into my hand: a few slices of salami, a hunk of Swiss cheese, and two slices of bread. We finished off the milk as well, passing it around and drinking straight from the jug. Glasses would have been too much of a pain without light to pour by. After lunch, more terrified boredom. Nothing to do but endlessly ponder: Is my family alive? Would I survive? I sat and thought for uncounted hours. Then something changed. There was silence..

Scene 31 (24m 0s)

Chapter 5 The silence was an enormous relief—sort of like coming out of that cave into the sunlight when I was ten. I peeled the headphones off my ears and pulled out the toilet paper plugs. They were stuck; it hurt to remove them. I heard someone—Joe maybe—say, “Can you hear me?” His voice was hollow, as if he were down a well. “Yeah,” I said. “Can you hear me?” he said again, a little louder. Finally I caught on. I shouted, “Yeah!” “Good,” he shouted. “I think my ears were damaged by all that noise.” “Yeah, mine too,” I yelled back. “How you feel?” “Not good,” I yelled. “Darren?” Joe yelled. Darren looked up, but didn’t reply. “You okay?” Nothing. “Darren! You okay? What’s wrong?” Joe lit the candle. Darren’s face was scarlet. He stared sightlessly at a point about halfway between Joe and me. Joe reached out and put a hand on Darren’s shoulder. Darren batted Joe’s hand away and turned on him, screaming, “What’s wrong? I feel like I’ve been thrown into the gorilla cage at the zoo, and they’ve been using my head as a goddamn volleyball!” I felt pretty much the same way. Plus I was worried about my family. But screaming wouldn’t help anything. Joe stood up, walked behind Darren’s chair, and started rubbing his shoulders. Darren seemed to deflate, collapsing with his head down on the kitchen table. Joe stood behind him, trying to comfort him..

Scene 32 (24m 58s)

Finally Darren looked up from the table and muttered something I couldn’t hear. “It’s okay,” Joe yelled. “I’m going to see if there’s anything on the radio.” He picked up the candle and used it to find a clunky old boombox on the counter. He carried the radio to the kitchen table and blew out the candle, plunging us again into total darkness. After a while I heard a soft hiss of static waxing and waning as Joe dialed through the stations. I imagined he had the volume cranked up to the max so we could hear anything at all, but still the static sounded faint and hollow. We bent forward, pressing our heads together close to the radio, and listened to static for about an hour. Every now and then, I could hear a roll of thunder coming from outside —not the painful continuous booms we’d been suffering through, only a natural clap of thunder sounding soft and echoey in my messed-up ears. The sulfur stench was stronger. I could smell it everywhere now, not just near the windows and doors. “I’ve been through AM and FM three times each. There’s nothing!” Joe shouted. “Why?” I yelled. “I don’t know. I was getting all the usual stations on it yesterday. Maybe the ash somehow interferes with radio reception.” Darren flipped open his cell phone. The bluish light from the screen illuminated his face, hanging ghost-like in the gloom. “Cell phone still doesn’t work.” Joe held down the button on his watch and used its faint light to stumble to the house phone. “It’s dead, too,” he yelled. “How long is everything going to be down?” Darren asked. “I don’t know.” Joe shook his head slowly. “Why’s the water work?” I shouted. “Everything else is down, why should that be any different?” “Good point,” Joe yelled. He lit the candle and we went upstairs, cleared the bedding out of the Jacuzzi and filled it with water. The water trickled slowly out of the spigot. It smelled funny, too, a bit like rotten eggs. I tried a sip—it didn’t taste too bad. After that, we got an armload of towels and walked around the house by candlelight, jamming them under the doors and along the windowsills. It.

Scene 33 (26m 3s)

didn’t help, though—the rotten egg smell kept getting worse. As the afternoon and evening wore on, the thunder outside got louder. I didn’t know if the storm was getting worse or if my ears were getting better; the latter, I hoped. Joe wanted to cook some of the stuff in the freezer for dinner, but the gas cooktop wouldn’t light. He sniffed it and said there was no gas, although I didn’t see how he could tell—I couldn’t smell anything but sulfur. So we ate bread again, this time with some lettuce and fresh peaches. Darren wanted salami and cheese, but Joe overruled him. He said we needed to save the food that would keep the longest. As we were finishing dinner, I said, “Thanks for taking me in and feeding me and all. I really appreciate—” “Don’t be silly,” Darren said. “That’s what neighbors are for.” “Well, thanks. You guys are great neighbors. At least that’s what Mom always—” Thinking about Mom got me choked up, and I had to stop. We sat in silence then, waiting for nighttime, although we could have gone to bed whenever—it was still pitch black and had been all day. Then the explosions started again..

Scene 34 (26m 51s)

Chapter 6 Boom-boom-boom-boom-boom! The continuous thumping roar hurt my ears and drowned out the normal thunder. Joe flicked on the Maglite and used it to find a box of tissues on the kitchen counter: Puffs with lotion. Slimy, but they felt better than toilet paper while I was jamming some into my ears. Darren pressed the headphones into my hands, and I slapped them over my ears. We sat in the kitchen, going crazy with both worry and boredom. The fear rested on my stomach like a dull weight, pressing down and making me queasy. I didn’t want to go to bed and try to sleep through another night of that horrid noise, and Darren and Joe must have felt the same way, because neither of them made any move to leave. At least I knew what it was now. That made the current round of explosions a little better than yesterday’s, when the boredom and terror were compounded by wild speculation. This, I figured, must be the noise of some kind of secondary eruption. There was still plenty of reason to be scared, of course. My house had been hit by something thrown off by the eruption. What if Darren and Joe’s house got hit, too? We weren’t even taking cover in the bathtub like last night. Besides, the noise itself was terrifying without even thinking about the awesome eruption it represented —powerful enough to hurt my ears from nine hundred miles away. I endured hour after hour of nothing: nothing to see but blackness, nothing to hear but machine-gunned explosions, nothing to do. Nothing to smell but—well, okay, there was something to smell: sulfur and yesterday’s sweat. My breathing slowed, and the fear gave way to numb, wary boredom. The noise lasted for a little over three-and-a-half hours by Darren’s watch. And then, mercifully, the explosions stopped again. I yanked off the headphones and pulled the Puffs out of my ears. I heard a normal thunderclap as if from a storm. It sounded puny and hollow after the aural bombardment we’d just endured..

Scene 35 (27m 57s)

Joe lit the candle and, by its light, led me to the guest room upstairs. There was another box of Puffs on the nightstand, so I set my headphones beside it, within easy reach. Joe turned down the covers and left the lit candle and a book of matches on the bedside table. I kicked off my shoes and climbed into the bed fully dressed in the same disgusting jeans and T-shirt I’d been wearing for two days now. I blew out the candle, rolled onto my left side, and fell asleep the instant my head settled on the pillow. * * * The next day started out pretty much the same. It was still pitch black. Ash still fell in a thick blanket past the windows. We could still hear normal, storm-like thunder. It sounded maybe a little louder, which I took as a hopeful sign that my ears might be improving. The storm had been going on for a day and two nights now. Perhaps it was related somehow to the volcano. The other weird thing about the thunder was that I hadn’t seen any lightning, and there was no rain, at least not that I could see by candlelight through the windows. When I turned on the kitchen faucet, hoping to wash up, nothing came out. Hot, cold—neither worked. I checked the downstairs bathroom; there was no water there, either. So we’d have to drink from the bathtub now. And the toilets were only going to flush one more time. That was a problem —it was going to get stinky in a hurry. Joe served more lettuce for breakfast. He wanted to finish all the perishables. Darren grumbled about it some—I didn’t like a salad for breakfast any better than he did, but I figured Joe was making sense. Complaining wouldn’t improve anything. Besides, I was a guest—they didn’t have to share. After breakfast Joe took me to the master bedroom and got some clean clothes out of his closet for me. They didn’t fit very well. Darren and Joe are both a bit taller than I am and a lot heavier. Not fat, exactly, but big enough that Joe’s jeans bunched uncomfortably around my waist and his T- shirt was like a maternity blouse. Still, it beat my filthy clothing. Late that morning we noticed something new. There was an occasional flash of lightning visible in the windows through the ashfall. It was always accompanied by an immediate clap of thunder—the lightning was close..

Scene 36 (29m 2s)

As the day wore on, it got steadily brighter. At first, we could only see during the lightning flashes. But by late afternoon, it wasn’t pitch-black anymore. Oh, it was still dark, but I could see my fingers if I stood by a window and waggled them near my eye. It was like a moonless, overcast night—about like the darkest night I’d ever experienced until two days ago. But it beat the cave-like blackness I’d woken up to that morning. Joe played with the Maglite for a while, swapping D-cells to it from the boombox until it had a pretty strong beam. He tried the boombox again too, quickly scanning all the channels. Nothing. He shut it down to save the batteries. It started to rain. Fat black raindrops splattered on the windows and washed streaks in the fine dust that clung to the panes. It was strange; I would have thought the rain would wash the ash out of the sky, but it didn’t work like that. The rain fell, and the ash kept coming down, at about the same rate and density as before. It didn’t even clump up like ash from a fire. The rain had been falling for a couple hours, and we were thinking about dinner, when we heard a cracking sound and then a huge crash from outside. Joe grabbed the Maglite and ran for the front door. Darren and I followed him. The ash had blown up over the front porch, covering it in a layer a couple inches deep. It was dry under the porch roof, so our feet stirred up the stuff. It rose in little clouds around us. I took a deep breath, which was a mistake, earning me a mouthful of sulfurous grit. It tasted nasty and set off a fit of hacking coughs. I tried to breathe shallowly and through my nose after that. A concrete stairway led to the yard from the porch—four steps, I remembered. The bottom two were now buried in ash. Joe took a tentative step into the ash. His foot sank a few inches and pulled free only with a visible effort. I followed him, and we slogged around to the side of the house in the direction the noise had come from, while Darren waited on the porch. Walking in the wet ash was like walking in thick, wet concrete. My sneakers kept trying to pull off my feet. Scrunching up my toes helped some. The side of the house was a mess: a confused tangle of wood, asphalt shingles, and metal guttering. The ash, heavy with water, had pulled down.

Scene 37 (30m 7s)

the old-fashioned, built-in gutters, taking the soffit and the edge of the roof as well. As we gawked, a load of wet ash landed with a splat amid the wreckage. We couldn’t see the roof very well, even in the powerful beam of the Maglite. What if more of the roof fell while we were standing there? I took a couple steps backward. Then another worry occurred to me: How long would the house itself be able to withstand the weight of the ash and water on the roof? Joe shrugged and plodded back to the front door. As we were closing the door behind us, we heard a crack and crash from the other side of the house. I assumed the gutters on that side had just fallen. Ash clung to us everywhere. Joe and I beat at it, knocking clumps of wet ash onto the entryway floor. It was hopeless, though; the stuff was so fine it clung to our clothes and skin despite our efforts. The ash looked almost white in the dim light, giving us a ghostly aspect. Maybe we were ghosts of a sort, spirits from the world that had died when the volcano erupted. Now we haunted a changed land. Would there be any place for us in this new, post-volcanic world?.

Scene 38 (30m 57s)

Chapter 7 It was brighter the next morning. Still dark—the ash continued to fall—but at least we could walk around the house without crashing into stuff. Joe and I dragged the propane grill into the kitchen from the back deck. We wet rags before we went out and tied them around our mouth and nose, like old-time bandits. That kept most of the grit out of our mouths and lungs. The grill was buried in a foot and a half of heavy, wet ash. I cleaned off the top of the grill while Joe tried to pull it free. Even when both of us heaved, the legs wouldn’t come up. Joe fought through the ash to his detached garage and returned with a shovel. I volunteered to dig—it took about ten minutes to free the grill. Miraculously, the grill worked. The smoke wasn’t going to do their kitchen ceiling any good, but neither Joe nor Darren seemed to care. Their house was pretty much wrecked, anyway. I’d noticed water running down one of the guest room walls that morning, presumably from holes ripped in the roof when the built-in gutters had fallen. We ate steaks for lunch, Black Angus filet mignon. They tasted heavenly after a day and a half of salads for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Joe told me to eat as many as I wanted since they were all going to spoil anyway. I ate three. That afternoon I was napping off the huge lunch in an easy chair in the living room when somebody started banging on the front door. They were whaling on it, too—the noise was almost louder than the thunder, loud enough to wake me up. I stood and tried to shake the postnap loginess out of my brain. Joe went to get the door. Something made me suddenly nervous. Who would be out in the ash? And why? Whoever it was kept hitting the door, slamming something into it so hard that I wondered if it would break. I suppressed a sudden desire to move away—hide in the back of the living room or go.

Scene 39 (32m 2s)

upstairs, maybe. Instead, I moved to the living room doorway where I could watch Joe in the foyer. “Don’t answer,” Darren said. I nodded. “Why not?” Joe replied. “It’s probably just the neighbors. We ought to be banding together, helping each other out.” “You don’t know that. It sounds like they’re trying to break down the door.” Darren retreated past me into the living room. “If they weren’t knocking that loudly, we wouldn’t be able to hear them over the thunder.” Joe peered into the glass peephole set into the door. “I can’t see anything. Too dark.” He unlocked the deadbolt and twisted the knob. The door flew all the way open, pushed violently from outside. Joe stumbled backward as the door struck him. Three guys burst through. They were so coated in ash that it was impossible even to tell what color their hair or skin was. The lead guy was carrying a baseball bat. I shrank back into the living room, hoping they wouldn’t notice me. My heart lurched, starting a hammering thump in my chest. I thought about running, following Darren toward the far side of the living room, but I would have had to cross the large open doorway between the living room and foyer. They’d have seen me for sure. The second guy had a length of heavy tow chain, and the last one carried a tire iron. Baseball Bat advanced on Joe, waving his weapon wildly and yelling, “Where’s the stuff? What you got? OCs? Boo? Ice? Tell me, old man!” Joe held out both his hands, palms up. How he managed to react calmly was beyond me. I was shaking with a mixture of fear and adrenaline. I sent silent, useless orders to my body: Calm down. My breathing was ragged, so I focused on that. Two quick breaths in through the nose, two quick breaths out through the mouth. That helped some. Darren turned and ran toward the master bedroom. “Stop that peckerwood!” Baseball Bat ordered. Chain ran toward Darren, with Tire Iron right behind him. They were running right past me. I froze, unsure what to do. Chain ran by. He was swinging his weapon—he passed so close I heard the links clinking even over the roar of my labored breathing..

Scene 40 (33m 7s)

On impulse, I kicked out—a low, sweeping roundkick. Chain was already past me, but I kicked Tire Iron right in the shins, taking him down. His weapon clunked as it hit the wood floor. He yelled and reached for the tire iron. I just stood there and watched him grab the tire iron and push himself onto his knees. I knew I should follow up on my kick, but I hadn’t been in a real fight since sixth grade. And those didn’t count as real fights, anyway— they were just stupid schoolyard stuff. Nothing like this. Tire Iron started to stand, staring at me murderously. If I didn’t do something—now—he’d cave in my skull. I stepped toward him and hit the side of his neck with a palm-heel strike. It’s supposed to stun an opponent by interrupting the blood supply through the jugular, but I never figured I’d have to use it for real. It worked beautifully. The steel bar clattered to the floor, and Tire Iron followed it, falling sideways with a heavy thump. I stood over him for a second, panting and trembling, and then looked around. Chain was at the back of the living room, chasing Darren, who had disappeared into the master bedroom. I glanced at Joe in time to see Baseball Bat take a swing at his head, but I was too far away to help. Joe had the presence of mind to step toward Baseball Bat instead of away, so he got clubbed by the guy’s hands instead of taking the murderous hit of the bat’s business end. Still, Joe went down. I screamed, taking a step toward him. Baseball Bat raised his weapon over his head and moved to meet me. Instinctively, I crouched in a sparring stance, hands up by my chin. My thoughts raced. What could I do? If he chopped down with the bat, maybe I’d sidestep and go for a wrist grab and joint lock. I heard a noise like a pair of M80 firecrackers behind me. Blam-Blam! Something fell, tinkling to the floor with a noise like ice dropping into a glass. Baseball Bat lowered his weapon and took a step backward, so I risked a glance behind me. Darren was stalking through the living room, a big chrome pistol clutched in front of him in a two-handed grip. Chain lay beside the sofa; blood gushed from his ruined skull and soaked the rug. My nostrils filled with the copper tang of blood blended with a faint fecal stink. I fought back vomit..

Scene 41 (34m 12s)

Darren got close enough to see Joe, motionless on the floor of the entryway. Darren screamed—an inhuman, animal yowl. Baseball Bat turned and took a step toward the door. He reached for the doorknob. Blam-Blam! Darren shot him in the back of the head. His face exploded. I heard a thunk as part of it hit the door and then a dull thump as Baseball Bat’s body slumped to the floor. A dark stain marred the door, like someone had hurled a blood-filled water balloon against it. Tire Iron moaned and pushed himself up on one arm. Darren screamed again. I shouted, “Darren, take it—” “Yearrrgh!” Darren pushed the pistol against Chain’s temple. Blam- Blam! His head pretty much burst, showering my legs with blood and bits of hair and skull and brain. The scent of blood and shit was overpowering now. Joe groaned loudly and rolled over. Darren’s gaze twitched from corpse to corpse, rage disfiguring his face. I ran for the front door..

Scene 42 (34m 52s)

Chapter 8 The door snagged on Baseball Bat’s body, but there was enough space for me to slip through. Behind me I heard Joe call out weakly, “Alex . . .” I didn’t care. Didn’t care what he had to say. Didn’t care where I was going, either. I had to get away. Had to leave that horrible, gore-splattered foyer. Had to clear the stench of blood from my nostrils—if that was even possible. Running through the ashfall wasn’t easy. Water and ash scoured my face. With every step, my feet sank into the gooey mess. It was less like running than doing a fast, high-step march. I couldn’t see very far, and I wasn’t really looking around, but the street seemed deserted. There were no moving vehicles, only half-buried parked cars. No sign of any people. No noise except the thunder. Very little light other than the occasional flash of lightning. I made it only two blocks before I got too winded to keep going. I’d lost my shoes somewhere, sucked off by the wet-concrete-like ash. I rested my hands on my knees and stood there a minute, panting. The image of Tire Iron’s head exploding invaded my brain. I vomited. The steaks tasted a whole lot worse coming up than they had going down. I didn’t know if it was running or spewing, but something got me thinking straight again. I needed water, food, and some kind of protection from the ash. Shoes, too. Running around like a madman would get me killed in a hurry. But I couldn’t go back to Darren’s house. I doubted I could ever look at him again without seeing that rage-contorted face. And just thinking about returning to his gore-drenched foyer—no way. But I had to go somewhere. I dragged myself slowly back down the road toward my house. The ash had permeated my socks and was abrading my skin. Every step hurt the sides of my feet where my skin was soft and thin. The ash caked the inside of my mouth and got into my eyes, making them water and causing me to blink constantly..

Scene 43 (35m 57s)

The front of my house had collapsed further under the weight of the ash. My room and my sister’s were pretty much pancaked. The gutters had ripped off the house, but we had modern aluminum gutters, unlike Darren’s, so it hadn’t done much damage. The back part of the house looked okay. I found a window the firefighters had left open and climbed in. The inside wasn’t too bad. A lot of ash had blown in through the open windows, but so long as I didn’t walk in it and stir it up, it didn’t bother me. I checked the faucet in the kitchen sink. It sighed when I opened it, air rushing into empty pipes. No water. I got a warm Coke out of the fridge and used the first swig to rinse my mouth. That got me coughing. When I pulled my arm away from my mouth it was spotted with bloody flecks. That scared me; coughing up blood couldn’t be good. But what could I do about it? I finished off the Coke, slugged down another, and devoured two apples. I needed to pee. The downstairs bathroom and the one my sister and I shared were in the wrecked part of the house, so I went up the back staircase to the master bath. As I was getting ready to do my business, I thought of something. Grody though it was, I might need the toilet water. The water in the tank would be clean, right? And one of my friends had this cat, George, that always drank from the toilet—it hadn’t killed him. I went downstairs and peed out an open window into the ash. Back upstairs in my parents’ bedroom, I stripped off the now repulsive clothing Joe had lent me and threw it in the trash. Ash clung to the inside of my underwear. My clothes were all burned or buried at the front of the house, but Dad’s stuff fit me okay. Way too loose in the waist, but otherwise not bad. It was getting cold, which worried me. I thought for a moment and figured out it was the last day of August. The volcano must be messing with the weather somehow. How cold would it get? I had no way to answer that question, so I ignored it for the moment. I put on one of Dad’s long-sleeved shirts over a T-shirt. I slept in my parents’ bed that night, fully clothed. Under the oppressive smell of sulfur, I caught a hint of my mom—a faint whiff of the Light Blue perfume we bought her every year for Mother’s Day. Lately I’d been so consumed with fighting with Mom that it never occurred to me what my life might be like without her. Without Dad’s benevolent disinterest. Without the brat, my sister. Who would I be, if they were all gone?.

Scene 44 (37m 2s)

I clenched my eyes shut and refused to cry. Would I see them again? Yes, I decided. If they were alive, I would find my family. There was no way they could come home to get me. Nothing short of a bulldozer would be able to move in all that ash. And if the gang that had invaded Joe and Darren’s house was any indication, Cedar Falls would only get more dangerous. Tomorrow, I’d set out for Warren to find my family. The journey might be impossible, but I had to try. I had to find my mother. With that resolution, I drifted off to sleep. I slept badly. Sweat-soaked nightmares featuring Tire Iron woke me a few times. Baseball Bat invaded my dreams, too. Morning announced itself with a shift in the darkness, from pitch black to merely dark and gloomy. I rolled over and went back to sleep, the first solid sleep I’d had in days. A coughing fit woke me for good. No blood this time, thank God. I needed water, so I got up and found a cup in the bathroom. I took the lid off the toilet tank and scooped out some water. It smelled okay. I sipped it. It tasted fine, sweet even. I drank that cup and dipped myself another. I brushed my teeth with my dad’s toothbrush and rinsed my mouth with a tiny sip of water. My freshly brushed teeth felt heavenly. Maybe it was the normalcy of getting up and brushing my teeth, or maybe it was just having one part of my body clean, but I felt much better. Breakfast was wilted lettuce and two more apples. After breakfast, I searched for supplies. If I planned to honor the promise I’d made the night before, to find my family, then I needed to get prepared. My backpack was buried in my room with everything else. But I needed a way to carry supplies, so I dug through my dad’s closet. Way in the back, I found an old knapsack from back when he used to hike and ski. I wished it were bigger, but it would have to do. I got one extra change of clothes out of my dad’s closet, but I couldn’t afford the space in the backpack for any more clothing than that. I did take two T-shirts though—I might need the cloth to make breathing masks. I also snagged a pair of Dad’s work boots. They fit okay if I wore two pairs of socks. We had six bottles of water in the fridge—I packed them all. Then I threw in all the food that would fit: cans of soup, pineapple, and baked beans, as well as all the cheese and ham from the fridge. I found an old,.

Scene 45 (38m 7s)

manual can opener in the back of the knife drawer. I dug a few packages of peanut-butter crackers out of a cabinet and packed those, too. It didn’t seem like very much food. If it took longer than a week to get to Warren, I’d be in trouble. I tossed in a spoon, three books of matches, and a couple of candles. I figured I’d want a knife, both to use as a weapon and to eat with. I thought about the butcher knives, but they seemed like they’d be too clumsy. I grabbed Mom’s favorite knife instead, a five-inch mini-chef’s knife that she kept honed to a wicked edge. I tested it on one of the T-shirts, cutting a strip about the right size to cover my mouth and nose. I didn’t want the knife in my backpack—too slow to get at. So I took off my belt and cut a horizontal slit in the leather. That worked okay as a makeshift sheath; it kept the knife at my hip with the blade angled away from my body. In the mudroom, I got the biggest rain poncho I could find, one of my dad’s. It had a hood and enough extra girth to cover both me and my pack. I also grabbed the spare garage key Mom kept there on a hook. All my keys were gone, another casualty of my collapsed room. Then I trekked back upstairs. I scooped water out of the toilet tank and drank until I felt I might be sick. I wet down my cut T-shirt bandanna and tied it around my face. I was ready to go. I got as far as the back door on the first try. The door itself pulled open fine, but there was ash piled at least a foot and a half deep against the storm door. I couldn’t force it open. I gave the screen door a frustrated kick and then closed the back door and locked it. (As I turned away, I realized there was no point to locking the door, but whatever.) I climbed out a window instead. Slogging to our detached garage through the ash was painfully slow. I sank three or four inches with every step and had to struggle to wrench my feet free. If I had to cover the 140 miles to Warren like this, it might take a year, not a week. The pedestrian door to our garage opened inward, thankfully. When I pushed it open, the ash flowed in, so I couldn’t close the door behind me. I saw a folded plastic dropcloth on a shelf and thought about using it as a makeshift tent. Of course it wouldn’t fit in my pack. I moved some stuff to outer pockets and took out a couple cans of food to make room..

Scene 46 (39m 12s)

My bicycle was leaning against the garage wall next to my sister’s. I wheeled it out into the ash-covered backyard. I mounted and put my feet to the pedals—I was on my way to Warren!.

Scene 47 (39m 25s)

Chapter 9 I didn’t even make it out of the backyard. As soon as I stood on the bike, both tires sank into the muddy ash. It was slick, and within a few feet I was stuck. The back wheel just spun and carved a trough. I stepped off the bike, wrenched it free, and tried again. Same result. It was hopeless. I could make better time hiking, not that hiking would get me to Warren this year. I pulled the bike free again and wheeled it back into the garage. Even that short trip had left it coated in nasty white-gray goop. I shrugged off my pack and sat on the garage floor to think. There had to be a better way to travel. I hadn’t seen any cars moving—they’d probably get stuck instantly. Plus, I wondered what the ash would do to a car’s engine. Nothing good. Walking was horrid because with every step my feet were swallowed by the stuff, and biking didn’t work because the wheels sank and couldn’t get traction due to the surprising slipperiness of the ash. It was sort of like a deep snowfall. Snowshoes might have worked if we’d had any. Maybe a couple of boards strapped to my feet? Or skis . . .? When I was little, my dad had been an exercise nut. He’d run in the summer and ski cross-country when there was enough snow. Then he hurt his knee and got kind of pudgy. But his skis might still be in the garage somewhere. I hunted for a couple of minutes and found them, stacked out of sight on a shelf above my head. I dragged everything down to the floor of the garage. Two skis, a pair of boots, two poles, and a pair of ski goggles. Everything was covered in dust, but that was okay. It’d get a lot dustier the moment I stepped outside. I took off my boots, tied them to the outside of my pack, and slid into the ski boots. I put on the ski goggles and everything turned pink. Typical Dad: Even his ski goggles were rose-colored. At least they’d keep the ash out of my eyes..

Scene 48 (40m 30s)